106th Transportation Battalion

INTRODUCTION

The 106th Transportation Battalion is now and always has been a battalion with a great vitality of spirit and a deep sense of pride in successful mission accomplishment. The battalion's soldiers are among the very best and the busiest in the entire Army. Since the 106th was reactivated in 1955, its most compelling characteristic has been decentralized operations. The battalion's companies and trailer transfer points (TTP) have been widely dispersed since at least 1958.

The 106th has led a nomadic existence since its reactivation. The battalion headquarters has had four “permanent” homes: Bussac, France (near Bordeaux: 1955 – 1958); Croix Chapeau, France (near La Rochelle: 1958 – 1963); Bremerhaven, Germany: (1963 – 1970); and Ruesselsheim, Germany: (1970 – present). In addition, the battalion has had two temporary homes. A significant element of the headquarters was based in Orleans, France from May 1966 – March 1967, during Operation FRELOC. The second was in Lee Barracks, Mainz, Germany, from December 1979 – December 1981, during the renovation of Azbill Barracks.

Possibly because of the frequent moves, the battalion's records are nearly nonexistent. The history which follows has been pieced together like a jigsaw puzzle with many lost pieces. Even though some details may be missing, the important thing is to capture the spirit and dedication or the thousands or young men and women who have been in the 106th Transportation Battalion throughout the years. Whether drivers, mechanics, cooks, clerks or communicators, they are all essential in providing a first class motor transportation service to the United States Army, Europe.

We have a sign in the battalion headquarters with pictures of our current soldier of the month and quarter. The sign says: “Welcome, soldier, to the 106th Transportation Battalion: The highest mileage truck battalion in the United States Army. These and many other dedicated soldiers have gone before you. It is your turn now. Hold your head high and make your contribution to our tradition."

Obviously, many things have changed since 1955. What certainly has not changed is the extraordinary dedication with which the soldiers of the 106th Transportation Battalion continue to serve our country.

The 106th Transportation Battalion

Primus Inter Pares - First Among Equals

The Expediters

106th TRANSPORTATION BATTALION CREST

THE FLYING TRUCK WHEEL REPRESENTS TRANSPORTATION BY WHEELED VEHICLE, WHILE THE SCROLL REPRESENTS THE ROADS OVER WHICH THE UNIT IS REQUIRED TO OPERATE. THE MOTTO “PRIMUS INTER PARES” (FIRST AMONG EQUALS) REPRESENTS OUR RECORD OF ACHIEVEMENT HAULING OVER THOSE ROADS IN COMPARISON WITH SIMILAR ORGANIZATINOS. THE FIVE FLEURS DE LIS DENOTE THE FIVE CAMPAIGN PARTICIPATION CREDITS OF THE BATTALION IN WWII: NORMANDY, NORTHERN FRANCE, RHINELAND, CENTRAL EUROPE AND ARDENNES-ALSACE

“THE BRICK RED AND YELLOW USED IN THE DISTINCTIVE UNIT INSIGNIA (CREST) OF THE 106th TRANSPORTATION BATTALION ARE THE BRANCH OF SERVICE COLOR FOR THE TRANSPORTAITON CORPS. THE BLACK ENAMEL DISC SIGNIFIES CAMPAIGNS ON GERMAN SOIL.”

THE BEGINNING

The ancestral parent of Headquarters and Headquarters Detachment (HHD), 106th Transportation Battalion is the 522nd Quartermaster Truck Regiment. The 522nd Quartermaster was constituted on 25 February 1943 and activated 15 April 1943 at Fort Dix, New Jersey.

On 20 November, 1943, the regiment was broken up. Its elements were reorganized and redesignated. HBD, 2nd Battalion, 522nd QM Regiment became HHD, l06th Quartermaster Battalion (Mobile).

The battalion deployed to Europe and received participation credit for five World War II campaigns: Normandy, Northern France, Rheinland, Ardennes-Alsace, and Central Europe. The battalion was inactivated in Munich, Germany on 22 February 1946. While inactive, the unit was converted and redesignated the l06th Transportation Corps Battalion on 1 August 1946.

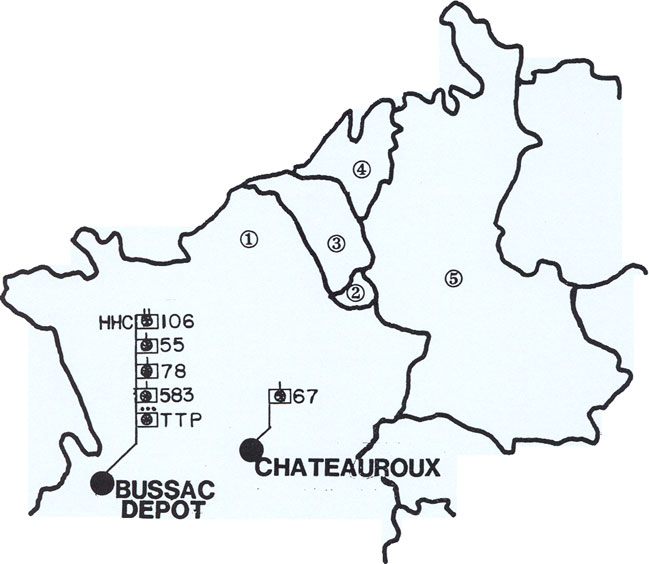

EARLY YEARS: 1955 - 1958

After World War II, Russia occupied the East European nations with the idea of establishing buffer countries between it and the democratic Europe. The constant threat of war between the Soviet Union and Western Europe created what was then known as the “Cold War.” In preparation for that the United States and European nations created the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in April 1949. The US Army established a comprehensive Communication Zone (COMZ) in France to support the defense of West Germany from an attack by the Soviet block armies. This COMZ included a line of communication that stretched from the ports of Northern France to Germany and supply depots scattered throughout France.

The 106th was redesignated as Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 106th Transportation Battalion (Truck) (Army) and allocated to the Regular Army, 1 February 1955. The battalion was activated at Landes de Bussac (near Bordeaux), France, on 18 March 1955. The early 1950s was the period of the buildup of the communications zone in France. Several truck companies were deployed to France as early as 1950. Others came from the assets of the 37th Highway Transport Command, then located in Turley Barracks. Mannheim. This was also a period when the World War II Reserve and National Guard units were being released from active duty and replaced by Regular Army units.

It is probable that, while no lineal relationship exists, the 806th Transportation Battalion was the forerunner of the l06th in Bussac. The 806th was an Army Reserve battalion called into active service in 1951 and deployed to France in late 1952. On 18 March 1955, the 806th Transportation Battalion was released from active service and reverted to Army Reserve status at Little Rock, Arkansas. With simultaneous activation/release from active service dates, it is almost certain that the l06th assumed the mission, task organization, personnel, equipment and facilities of the 806th.

The battalion's mission was to clear the port of Bordeaux and line-haul into another battalion's area of operations. The cargo then moved along the French line of communications into Germany for support of US Forces there. The next battalion to the east was probably the 2nd Transportation Battalion. The battalion's next higher headquarters was probably the 9th Transportation Group, and then located in Saran, France. However, the battalion could also have been assigned either to the Bussac General Depot, or directly to the Base Section, Communications Zone, Europe. At that time, Bussac was the headquarters of the COMMZ Europe.

Our estimate of the original task organization is based on inferences drawn from records of the 78th Transportation Company to personal correspondence and a 1959 battalion yearbook graciously donated to the l06th in 1983 by Colonel (Retired) Thomas L. Lyons. We gratefully acknowledge Colonel Lyons' contribution to this portion of our history.

The 55th Petroleum Company was part of the battalion from 1955 to 1958. It was detached when the Petroleum Command was formed. The 78th Transportation Company has been with the 106th since the battalion's inception. The 78th was activated on 3 April 1942 as Company H of the 46th Quartermaster Regiment, Camp Haan, California. In early 1943, the unit left New York aboard the USS Argentina for North Africa. In December 1943, the unit was redesignated as the 3488th Quartermaster Truck Company. Inactivated after the war, the unit was finally reactivated as the 78th Transportation Company on 21 October 1948 at Camp Kilmer, New Jersey. On 6 September 1951, the 78th was assigned to the 2nd Transportation Battalion, Camp Bussac, France. It was reassigned to the 9th Transportation Group on 21 November 1952. On 6 January 1953, the 78th became part of the 806th Transportation Battalion. There is no separate record of assignment to the l06th Transportation Battalion. While it is pure guesswork, there was probably also a trailer transfer point located in Bussac at this time.

The 67th Transportation Company, located in the Chateauroux Air Force Base complex, may also have been part of the battalion at this time. The battalion always had a company with a similar number. Based on correspondence, it is assumed that the 67th was assigned to the battalion from 1955 until sometime in 1958. Therefore, the initial task organization may have been:

- HHC, l06th Transportation Battalion, Bussac, France

- 55th Petroleum Company, Bussac, France

- 67th Transportation Company (Medium), Chateauroux, (Location estimated)

- 76th Transportation Company (Medium), Bussac, France

- Trailer Transfer Point, Bussac, France

The first battalion commander of the l06th was LTC Herbert N. Reed. Between his assumption of command on 18 March 1955 and LTC Thomas L. Lyons' assumption of command on 4 January 1959, there were three other battalion commanders: Major John R. Powell, Major Randall P. Smith and LTC Marcus A. Petterson. The exact command tenure of each of the first four battalion commanders is unknown.

Fall, 1956, was a time of change for the battalion. The 9th Transportation Group became part of the 37th Transportation Highway Transport Command on 1 October 1956 and moved from Saran to Nancy on that date. This marked the first time since World War II that all truck units in US Army Europe (USAREUR) COMMZ were under the jurisdiction of a single command the (37th THTC). The 9th's mission was to operate the intersectional highway transport service within the USAREUR COMMZ. On 1 November 1956, the 37th moved from Mannheim, Germany to Orleans, France. The 2nd Transportation Battalion at Etain and the 106th Transportation at Camp Bussac were assigned to the 9th Transportation Group on 1 October 1956.

The 77th Transportation Company (Light Truck) was activated on 1 May 1936. Except for a 15 month period, it had been on continuous duty in North Africa and Europe since arrival in Casablanca, French Morocco in 1943. In November 1950, the 77th deployed from Germany to Bordeaux, France. In France, they were attached successively to the 7711th Provisional Truck Battalion, the 109th Transportation Battalion (Truck), the 2nd Transportation Battalion (Truck) and, in November 1956, to the 106th Transportation Battalion, the 77th was located in Jeumont Caserne, La Pallice, France. La Pallice incorporates a modern sea terminal and is contiguously located just to the west of the historic sea port of La Rochelle. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Vieux Port (old port) of La Rochelle was the main embarkation point for thousands of French immigrants who sought their fortunes in the New World. Jeumont Caserne was dominated by a huge U-boat bunker built by the Germans in 1941 that housed the 3rd U-boat Flotilla during WWII. This bunker is still in place and was the filming location for the ending scene of the 1981 movie “Das Boot”.

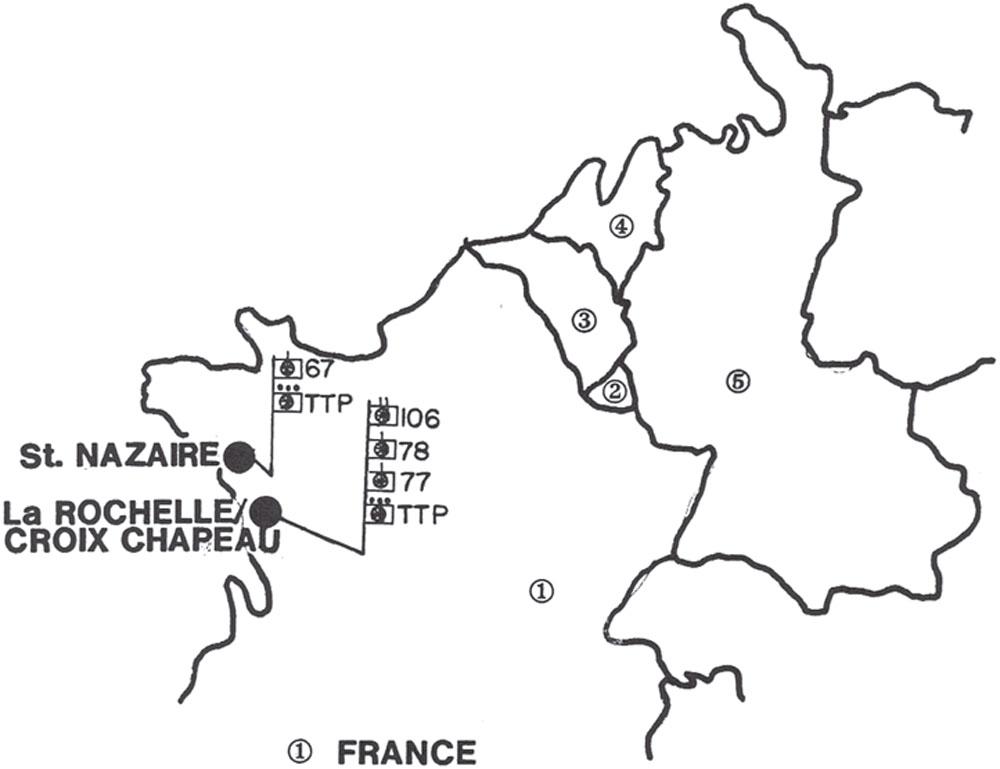

TASK ORGANIZATION PRE 1958

- 1 FRANCE

- 2 LUXEMBOURG

- 3 NETHERLANDS

- 4 BELGIUM

- 5 GERMANY

The 583rd Transportation Company (Light Truck) was originally constituted in May 1936, activated in 1942 at Fort Bliss, Texas, and inactivated 12 April 1950 in Okinawa, Japan. The 583rd was reactivated on 9 February 1955 at Camp Bussac, France. It was formed with a transfer of personnel from the 480th Transportation Company, West Virginia National Guard. The" 583rd was under the operational control of Camp Bussac until 1 October 1956. On that date it was assigned to the l06th.

The 595th Transportation Company (Heavy Truck) was activated at Fort Jackson, South Carolina on 5 October 1943. The unit arrived in England on 11 June 1944. It remained in Europe, stationed in both Germany and France (15 November 1950). The 595th was assigned to the 2nd Transportation Battalion from 1951 until 1954. When it was redesignated as a heavy truck company on 3 December 1954, it was assigned directly to Headquarters, 9th Transportation Group (Truck). On 1 October 1956, the 595th became part of the 106th Transportation Battalion.

Although it is again guesswork, both the 77th and the 583rd probably had trailer transfer points at this time. It is known that they did in 1959. The task organization in late fall 1956 was as shown:

- HHC, l06th Transportation Battalion, Bussac, France

- 55th Petroleum Company, Bussac, France (estimated)

- 67th Transportation Company (Medium), Chateauroux, France

- 77th Transportation Company (Light), La. Pallice, France

- 78th Transportation Company (Medium), Bussac, France

- 583rd Transportation Company (Light), Bussac, France

- 595th Transportation Company (Heavy), Braconne Ordnance Depot, France

- Trailer Transfer Point, La Pallice, France

- Trailer Transfer Point, Bussac, France

Other than the 77th Transportation Company, very little is known about 106th activities in 1957. During the year, the 77th Transportation Company participated in the first test of' the experimental roll-on-roll off (RO-RO) vessel, the USNS Comet. In October 1957, they rolled 110,000 miles in a 15 day period while supporting a logistical support exercise named LOGSPEC. While not documented, all units of the battalion probably participated in the series of new off-shore discharge exercises (NODEX) which were taking place along the northern coast of France at the time.

During 1958, the 77th ran more than one million miles. On 30 May, the 595th moved from Braconne to Fontenet, France

In July 1958, the battalion commander, LTC Petterson, was notified that the 106th was leaving its home in Camp Bussac and moving north to Croix Chapeau Medical Installation, in the vicinity of La Rochelle. Croix Chapeau, a small village located about ten miles east of La Rochelle. Croix Chapeau was the site of a fairly new 500-bed hospital that housed the 28th General Hospital, of which only 50 beds were used to support the Army in Southwestern France. The move began on 5 August. The 78th and 583rd Companies moved as well; but not north. In July 1958, both units were alerted for deployment to Lebanon. They convoyed to La Pallice and sailed aboard the USS General George M. Randall on 27 July 1958.

During the Lebanon crisis, both units were attached to the 201st Logistical Command (A), American Land Forces, Middle East. They arrived in Lebanon on 3 August. On 9 August, the 78th moved to Adana, Turkey (in the vicinity of the present Incirlik Air Base). They were further attached to the 38th Transportation Battalion, Adana Sub-Command. It is not certain, but the 583rd probably remained in Lebanon during the entire time of deployment.

When the crisis ended, both units returned to the 106th. The 78th arrived in France to find that it had a new home. They arrived in Croix Chapeau on 23 October 1958. The 583rd arrived back in Camp Bussac (Bordeaux) on 1 November 1958.

Thus, by late 1958, the l06th had begun its long history of wide dispersion and decentralized operations which continued for four decades.

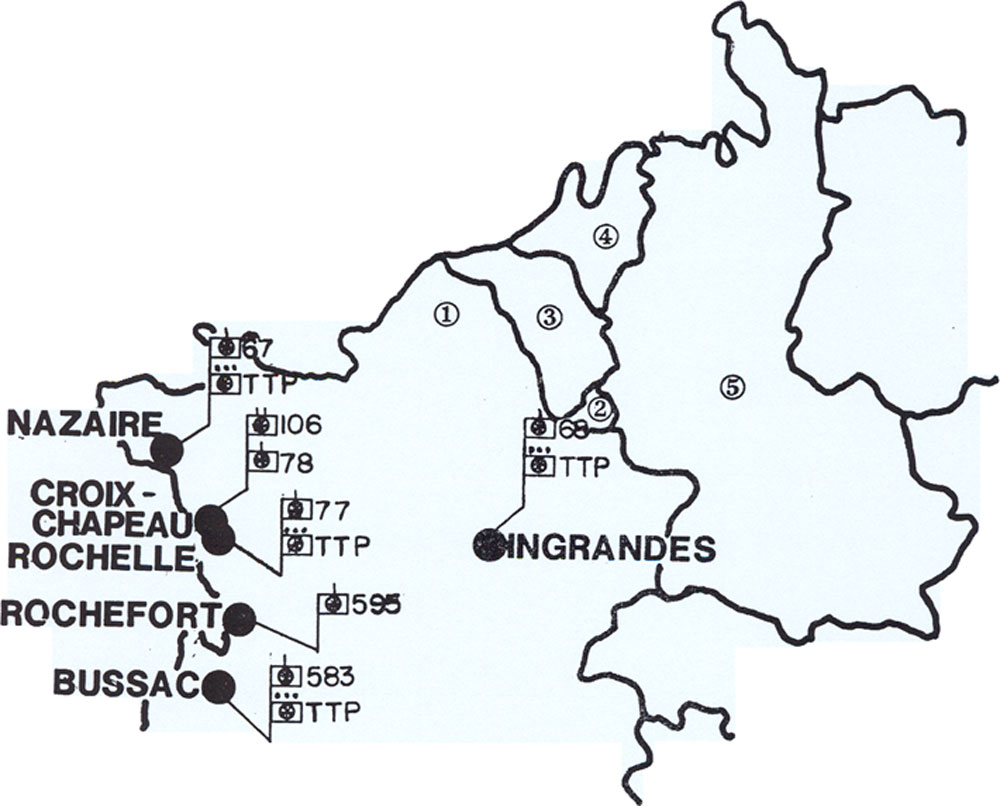

WESTERN FRANCE: 1959 - 1963

Coming from the Army War College via COMMZ Headquarters, LTC (later COL) Thomas L. Lyons assumed command of the battalion on 4 January 1959. It was to prove a very busy year.

The mission in 1959 included the now-familiar tasks of clearing the ports of La Pallice and Bordeaux, with subsequent line-haul from the western France Depot Complex to Orleans. Trailers were relayed by the 28th Transportation Battalion from Orleans to Nancy. The 2nd Transportation Battalion then moved the loads to Kaiserslautern, Germany, where they were delivered by the 53rd Transportation Battalion. A new task to clear the port of St. Nazaire was also added to the mission during 1959.

The battalion moved more than 110,000 tons of cargo; accumulating over 5 million miles in the process. The accident rate was a very low 7.76 per million miles. Battalion units participated in two exercises in the NODEX series during the year NODEX 20 and 21. NODEX 21 was the first ship-to-ship operational transfer of tow-away and drive-away cargo. The USNS Comet and the lighter USA John U. D. Page linked stern to stern while in stream. Vehicles from the l06th then drove from the Page to the Comet, picked up loads and returned to the Page. When the Page returned to the beach, the l06th drove to the nearest trailer transfer point.

During 1959, the l06th conducted a three level, Battalion Refresher Training School for officers, NCOs and enlisted members. The COMMZ Inspector General rated all l06th units excellent or above. The battalion rifle team placed second in the COMMZ competition.

There were also changes to the task organization. Not all the details are clear, but the 68th Transportation Company (Medium) at Ingrandes and the Ingrandes Trailer Transfer Point were attached to the l06th during 1959. The 1959 year book does not mention the 67th as being part of the battalion. Presumably, because of their close proximity in Ingrandes and Chateauroux, the OPCON of the 68th and 67th was changed at the time of the 68th coming into the battalion and the 67th leaving. Its guesswork, but the 67th may have been part of the Lebanon task forces in the summer of 1958. Upon return to France, the unit was assigned to another battalion (probably the 2nd Transportation Battalion).

This didn't last very long, however. In a separate letter COL Lyons stated that he had moved the 67th to St. Nazaire to accommodate the Comet RORO mission. The Comet shifted from a series of tests to a permanent port of call at St. Nazaire on 5 February 1959. The 67th move occurred later. The port of St. Nazaire, located north of La Rochelle, was familiar to many WWI doughboys since that was the first French soil they set foot on when they disembarked from their transport vessels.

The battalion also constituted a Trailer Transfer Point at St. Nazaire where 18 RO-RO operations were conducted during the year. Like its La Pallice counterpart to the south, the St. Nazaire Trailer Transfer Point was dominated by a huge U-boat bunker that was also built by the Germans in 1941. St. Nazaire was the home port for the 6th and 7th U-boat Flotillas during WWII. It is guesswork, but the chronological order was probably creation of the St. Nazaire Trailer Transfer Point, switch of the 68th and 67th and late in the year as the workload grew, regaining and moving the 67th to St. Nazaire. The 68th was probably detached from the battalion when the 67th moved to St. Nazaire. In a separate move the 595th moved from Braconne to Rochefort sometime during the year.

TASK ORGANIZATION 1959

- 1 FRANCE

- 2 LUXEMBOURG

- 3 NETHERLANDS

- 4 BELGIUM

- 5 GERMANY

The task organization at the end of 1959 was:

- HHC (redesignated HHD on 19 June 1959), Croix Chapeau, France

- 67th Transportation Company (Medium), St Nazaire

- 77th Transportation Company (Medium), La Pallice

- 78th Transportation Company (Medium), Croix Chapeau

- 583rd Transportation Company (Light), Bussac

- 595th Transportation Company (Heavy), Rochefort

- Trailer Transfer Point (67th), St Nazaire

- Trailer Transfer Point (77th), La Pallice (vicinity of La Rochelle)

- Trailer Transfer Point (583rd), Bussac

During this period, the 67th, 68th and 78th had five-ton tractors and ten-ton semi-trailers. The two light companies (77th and 583rd) had 2 ½-tons. The 595th was equipped with M26 ten-ton tractors and tank retriever trailers.

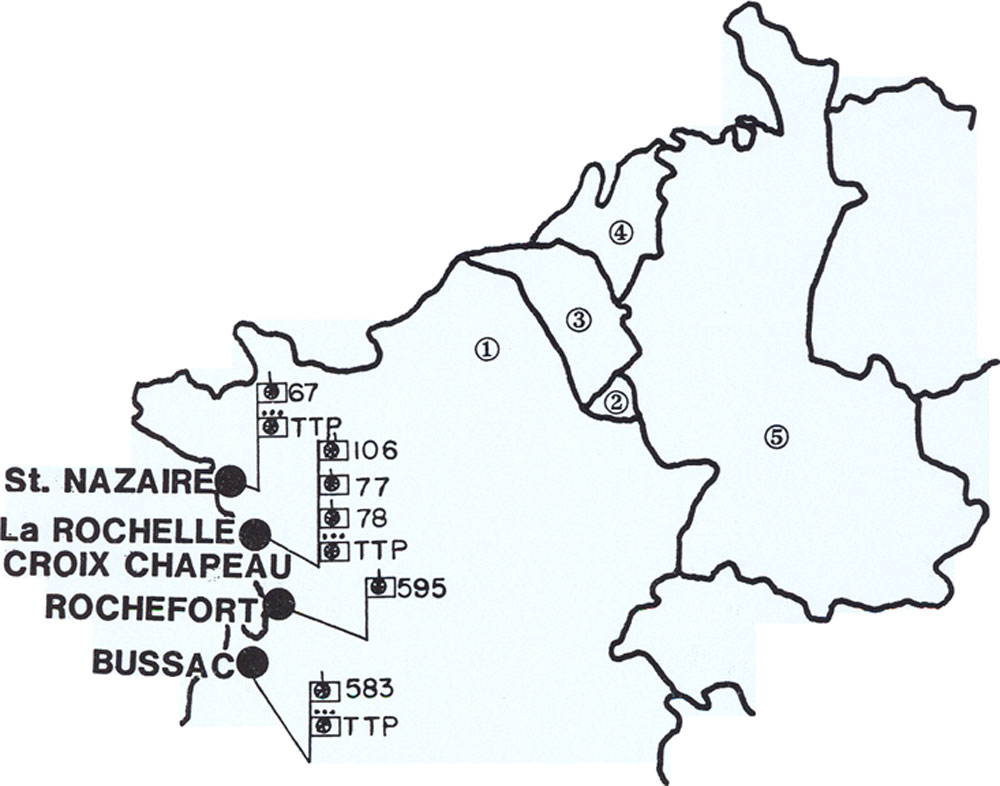

On 15 January 1960, LTC (Later BG) Edwin B. Owen assumed command. The task organization in mid-1961 remained the same:

- HHD, Croix Chapeau

- 67th Transportation Company (Med), St Nazaire

- 77th Transportation Company (Lt), Jeumont Caserne, La Pallice

- 78th Transportation Company (Med), Croix Chapeau

- 583rd Transportation Company (Lt), Bussac

- 595th Transportation Company (Hvy), Rochefort

- Trailer Transfer Point, La Pallice

- Trailer Transfer Point, St Nazaire

- Trailer Transfer Point, Bussac

LTC Owen left the 106th on 30 June 1961 to attend the Industrial College of the Armed Forces in Washington D.C. He was succeeded in command by LTC Scheftel on 14 July 1961.

Under LTC Scheftel, the battalion’s primary mission remained unchanged: port clearance and line-haul to the 28th Trailer Transfer Point at Chateauroux. They were also heavily committed to other activities, such as NODEX. Roundout (support of Berlin troop buildup) and the relocation of ammunition depots.

The troops had some fun supplying trucks and extras for the filming of the movie "The Longest Day". There were also good runs to Spain, hauling rebuilt vehicles from the ordnance depots to the Spanish Army. There were also occasional support missions for airborne exercises in the Pyrenees Mountains.

During his tenure, LTC Scheftel gained the 62nd Transportation Company (Med). The 595th Transportation Company was deployed to Germany in the Fall of 1961 where it was later attached to the 28th Transportation Battalion. In addition, the 1st Platoon of the 583rd was deployed to Chateauroux. The rest of the unit remained in Bussac.

TASK ORGANIZATION 1960 - 1961

- 1 FRANCE

- 2 LUXEMBOURG

- 3 NETHERLANDS

- 4 BELGIUM

- 5 GERMANY

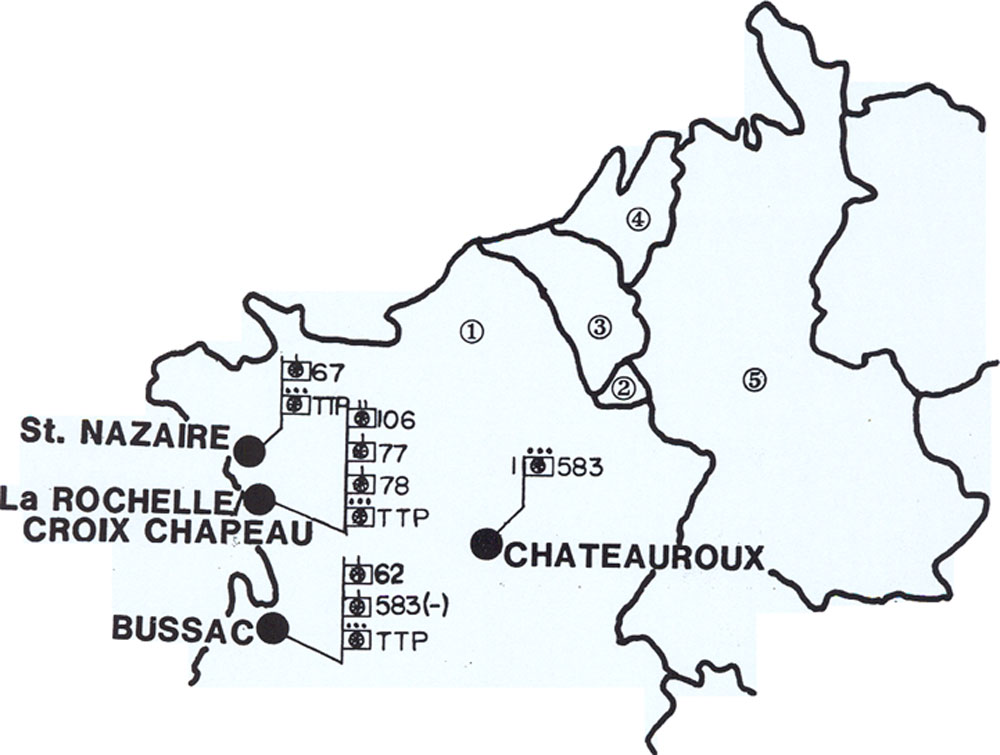

TASK ORGANIZATION 1962

- 1 FRANCE

- 2 LUXEMBOURG

- 3 NETHERLANDS

- 4 BELGIUM

- 5 GERMANY

So the battalion remained widely dispersed, with about 250 miles between its furthest elements. The task organization was as shown:

- HHD, Croix Chapeau

- 62nd Transportation Company (Lt), Bussac

- 67th Transportation Company (Med), St Bazaire

- 77th Transportation Company (Lt), Jeumont Kaserne, La Rochelle

- 78th Transportation Company (Med), Croix Chapeau

- 1/583rd Transportation Company (Lt), Chateauroux

- 583rd Transportation Company (Lt), Bussac

- Trailer Transfer Point, La Pallice

- Trailer Transfer Point, St Bazaire

- Trailer Transfer Point, Bussac

LTC (later COL) Brown commanded the battalion from 15 July 1962 until 1 July 1963. During the summer of 1962, all activities involved with clearing the port of Bordeaux were eliminated. The 583rd was reassigned to the 28th Transportation Battalion at Ingrandes, and the 62nd turned its vehicles over to the 77th Transportation Company while it made preparations for redeployment to Fort Eustis, Virgnia where it would be transferred to the 6th Transportation Battalion. The Bussac Trailer Transfer Point was inactivated with key personnel disbursed to the St. Nazaire and La Pallice Trailer Transfer Points. The two remaining Trailer Transfer Points were assigned directly to the 37th Transportation Command (Motor Transport), as Detachment 1, 37th TRANSCOM (MT) (St. Nazaire) and Detachment 2, 37th TRANSCOM (MT) (La Pallice). Thus, during this period, and up until November 1963, the battalion was closer together than at any time since. Only 150 miles separated the two operating locations. The battalion had six elements, located as shown.

LTC (later COL) Brown commanded the battalion from 15 July 1962 until 1 July 1963. During this period, and up until November 1963, the battalion was closer together than at any time since. Only 150 miles separated the two operating locations. The battalion had six elements, located as shown.

- HHD, Croix Chapeau

- 67th Transportation Company (Med), St. Nazaire

- 77th Transportation Company (Lt), La Pallice

- 78th Transportation Company (Med), Croix Chapeau

- Detachment 1, 37th Transportation Command (Motor Transport), St. Nazaire

- Detachment 2, 37th Transportation Command (Motor Transport), La Pallice

AU REVOIR FRANCE: 1963

On 24 July 1963, LTC (later MG) Del Mar assumed command. In the fall of 1963, French President Charles DeGualle ordered American troops out of his country. The subsequent rumor mill ran full throttle among HHD personnel as to potential sites where the battalion would be moved, with Rotterdam, The Netherlands; Antwerp, Belgium; and Bremerhaven, Germany most prominently mentioned. On 2 November 1963, the battalion received its orders to leave western France. Letter orders 241-1, Headquarters COMMZ Europe dated 2 November 1963, moved the battalion to Bremerhaven. Germany. An advance party comprised of key Communications Center personnel was the first to depart Croix Chapeau so communications would already be in place when the remainder of the HHD personnel arrived. Upon their arrival at the Bremerhaven Staging Area (later called Karl Schurz Kaserne), this party was surprised to find a small group of 106th enlisted personnel waiting to greet them. As it turned out, these troops had disembarked from a troop transport in Bremerhaven with orders for France, but the battalion actually came from France to them!

In the haste to move, the Army did not have time to approve funds for the move. LTC Del Mar left ahead of his convoys to arrange for government quarters for his soldiers and purchased food for the families with his own money. He authorized each bachelor one trailer and each family two trailers to load and haul their household goods. They loaded Privately Owned Vehicles (POVs) on trailers and covered them so they would not be seen. The last M52 tractor to cross the border had a white painted plywood sign on the back with a green frog and the words, “Never Again Froggie,” written under it. The Americans referred to the French as “Frogs.” Since American soldiers had fought in two wars for the defense or liberation of France, they felt insulted.

While not stated in the movement orders, the mission was to clear the Bremerhaven military ocean terminal and line haul to Giessen. The battalion headquarters and 78th Transportation Company moved from Croix Chapeau to Bremerhaven, where they were joined by Detachment 2, 37th Transportation Command (Motor Transport), which had moved from La Pallice to Bremerhaven. The 77th Transportation Company moved from La Pallice to Kassel military sub-post, Rothwestern AB, Germany. The 67th Transportation Company and Detachment 1, 37th Transportation Command (Motor Transport) moved from St. Nazaire to Bremerhaven. The 598th Transportation Company was detached from the 28th Transportation Battalion, attached to the l06th, and moved from Ingrandes, France to Kassel and was attached to the 106th in late 1963

LTC (later COL) Charles T. Forrester, Jr. commanded the battalion from 4 July 1964 until 1 February 1966. The Trailer Transfer Points were given alphabetic designations and the TTA had been the Trailer Transfer Point that moved from Bussac. In January 1965, the task organization was as shown:

- HHD. Bremerhaven

- 67th Transportation Company (Med). Bremerhaven

- 70th Transportation Company (Med). Kassel

- 77th Transportation Company (Med). Kassel

- 78th Transportation Company (Med). Bremerhaven

- 598th Transportation Company (Med). Kassel

- TTA. Bremerhaven

- TTB. Kassel

- TTD. Kassel

Because the M52 5-ton was designed as a tactical vehicle it was not designed for high speed traffic on highways. This caused a lot of wear on the vehicles. Instead, the commanders pushed for commercial tractors. In 1965, 37th Transportation Command turned in their M52 tractors for the International Harvester 205H tractor.

REVEILLE AT SUNDOWN: MAY 1966 - MARCH 1967

LTC (later COL) Wanek assumed command on 1 February 1966. This was a bleak time for the battalion. The Army was focusing its attention on the Republic of Vietnam. Cargo on the Bremerhaven LOC dropped sharply. The battalion was rapidly losing drivers as part of Operation Drawdown. Because so many soldiers were leaving Europe, there was a huge glut of POVs in Bremerhaven waiting to be shipped home. The 106th was utilizing only 25% of its capability. Worse yet, beginning in February 1966, the 106th was committed to provide as many as 120 guards for ammunition ships arriving in Nordenham, Germany. In addition, POV shuttle details consumed another 50 soldiers per day. With the 106th becoming an "ash and trash" battalion, there was speculation that it might be inactivated. Events proved quite the opposite. The battalion was about to enter an extremely busy period in its history. It was a period in which the 106th again demonstrated its unparalleled resilience and productivity in the face of adversity.

In 1965, General de Gaulle and France made the historic decision to leave the military arm of NATO. This meant, of course, that US Forces had to leave French soil. The decision was made, not only to withdraw US Forces, but also to clear all US depots in France. The deadline was set at 31 March 1967.

In April 1966, LTC Wanek was given the mission to clear the depots in western France. The initial concept of operation was for the 106th to clear depots in the general vicinity of Orleans and line-haul to Toul in the vicinity of Nancy. The code name for the operation was FRELOC: an acronym for French Line of Comminations. However, the initial tonnage figures were seriously underestimated. FRELOC grew geometrically into an all-consuming monster of men and equipment. During the height of FRELOC, the 106th ironically found itself clearing its original home in France: Bussac General Depot.

To appreciate the enormity of the mission, one must remember that the battalion retained responsibility for the Bremerhaven-Giessen line of communication. Even though much of it was deployed in France for 10 months, the battalion headquarters officially remained in Bremerhaven. Thus, the 106th was responsible for an extra- ordinarily extended line of communication, stretching from the North Sea port of Bremerhaven to Captieux, near the Atlantic Ocean port of Bordeaux. There is no way of knowing whether or not any U.S. Army Battalion ever had such a line of communication. There certainly can't have been very many.

Like the men of Tennyson's brigade, the 106th didn't waste time or effort worrying about the problems; they simply rolled up their sleeves and got the job done. The cost was high. Three companies, the 70th, 77th and 598th, were heavily committed to FRELOC for the entire 10 months operation. Equipment availability was a constant, almost insurmountable, problem. The problem was exacerbated by the depot's daytime only duty hours. Initially, the 106th hauled loaded trailers during the day and spotted empties during the evening. This meant that trailers stood idle at the depots' docks all night. The equipment problem became so critical that LTC Wanek. reversed the duty day. Empties were spotted the first thing in the morning for loading. The drivers had "Reveille at Sundown" and hauled all night.

This innovation may have saved the entire operation. It certainly enabled the 37th Group to have assets available for missions other than FRELOC. During FRELOC, the battalion accumulated over 6.5 million miles. Because of its distinguished accomplishments during FRELOC, the l06th was given the honor of pulling the last trailer out of France. In keeping with its tradition, the l06th accomplished the mission on time and in good order. The last tractor was driven across the border by SP5 Wilson, 77th Transportation Company, with LT Hefferran as shotgun, during 'the late evening of' 31 March 1967.

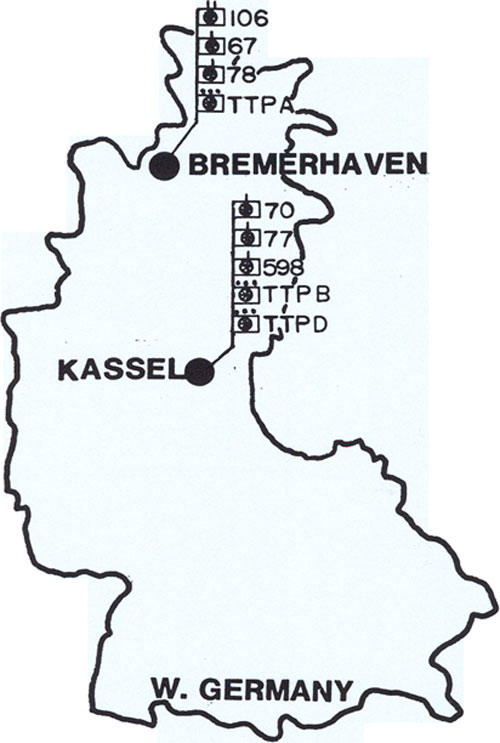

TASK ORGANIZATION 1963

- 1 FRANCE

- 2 LUXEMBOURG

- 3 NETHERLANDS

- 4 BELGIUM

- 5 GERMANY

TASK ORGANIZATION 1965

The conclusion of FRELOC brought major changes to the battalion's task organization. The 900-mile long LOC shifted to a 600 mile long north to south LOC. The 598th Transportation Company moved from Kassel to Mannheim in early 1967. With the move, the company was detached from the battalion and again attached to the 28th in Mannheim. The 1st Transportation Company and Trailer Transfer Point Hotel (TTH) in Nuernberg were transferred from the 28th to l06th during the same period. The 70th Transportation Company moved from Kassel to Butzbach in support of the Army Depot Complex in Giessen. Upon leaving France, the 77th Transportation Company and TTE were relocated to Dachau, Germany, near the Austrian border. The battalion headquarters, the 67th, 78th, TTA and TTB remained in Bremerhaven.

The task organization in the summer of 1967 was as shown:

- HBD, Bremerhaven

- 1st Transportation Company (Med), Nuernberg

- 67th Transportation Company (Med), Bremerhaven

- 70th Transportation Company (Med), Butzbacb

- 77th Transportation Company (Med), Dacbau

- 78th Transportation Company (Med), Bremerhaven

- TTA, Bremerhaven

- TTB, Bremerhaven

- TTD, Giessen

- TTE, Dachau

- TTH, Nuernberg

TURBULENCE IN BREMERHAVEN: 1970 - 1975

By late 1969, a long standing proposal to move the battalion headquarters to a more central location was approved. In January 1970, LTC (1ater COL) Conner moved the battalion headquarters and the 78th Transportation Company to their present home in Azbill Barracks, Ruesselsheim, Germany (between Frankfurt and Darmstadt).

Azbill Barracks was initially designated as Ruesse1sheim Kaserne. On 12 July 1967, it was redesignated Azbill Barracks in honor of Warrant Officer Roy Gorden Azbill. Azbill was an Army Aviator who died as a result of hostile action in the Republic of Vietnam on 10 December 1964.

Azbill was built in 1931. After the war it was used as a school and then for a civilian labor group unit. Few previous occupants of Azbill are known. However, in the 1961 - 1968 period it was occupied by HQ's 4th TRANSCOM and the 501st Transportation Company (Light).

The move left only the 67th Transportation Company and TTA in Bremerhaven. Two and a half years later the battalion left Bremerhaven completely. The 67th was inactivated in Bremerhaven on 1 July 1972. After 17 years, the 67th was no longer part of the battalion.

From 1971 to 1972, the 37th Transportation Command received the newer model International Harvester Commercial (IHC) tractors 4070 and 2000D models. The northern most battalion, the 106th, which had the longest run clearing cargo out of the Port of Bremerhaven received the IHC4070s. The IHC2000Ds had single axles and could not pull the 20-foot containers as well.

Two months later, on 31 August 1972, TTA was attached to the 78th Transportation Company in Ruesselsheim. Bremerhaven cargo was now cleared solely by rail.

Sometime after FRELOC, the 70th left Kassel and relocated in Schloss Kaserne, Butzbach. The unit later moved a few miles north to its present home on the Giessen Army Depot.

Another long time 106th Company, the 77th left the battalion in the same time frame. After 27 years of continuous service in the European theater, the 77th Transportation Company was inactivated in Dachau, Germany on. 25 June 1970.

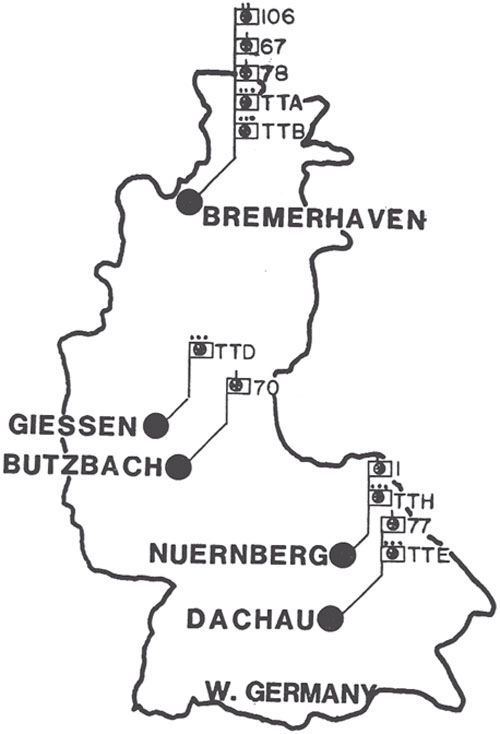

TASK ORGANIZATION 1967

By fall of 1972, the task organization was as shown:

- HHD, l06th Azbill Barracks, Ruesselsheim

- 1st Transportation Company (Med), Nuernberg

- 70th Transportation Company (Med),

- 78th Transportation Company (Med), Ruesselsheim

- TTA, Ruesselsheim

- TTD, Giessen

- TTH, Buernberg

The 78th was a light-medium company at this time. They had one platoon of 2 ½s which they used to support Rhein Main Air Base. Other than Rhein Main, business must not have been very good. On 1 October 1973, the 3rd Platoon of the 78th was attached to the 50lst Transportation Company in Kaiserslautern. This attachment lasted until July 1974, when the 78th turned in their 2 ½s and again became a medium truck company.

With the withdrawal from the Republic of Vietnam in the early 1970s, the national attention shifted again to Europe. This meant military highway assets were again needed in support of Bremerhaven-Giessen LOC. Initially, these needs were met by taking tractor assets of the TDA Refrigerator Platoon from the 53rd Transportation Battalion and assigning them to the l06th. In November 1974, the platoon moved to Bremerhaven.

Still, as the now of' cargo into Bremerhaven swelled, more assets were needed in the Bremerhaven area. By early 1975, the TDA platoon had been augmented to give it a limited maintenance capability. By March 1975, the battalion was actively looking for a site to reestablish a TTP in Bremerhaven. By this time, it was obvious that a full company was needed to service Bremerhaven-Giessen LOC. The 69th Transportation Company in Mannheim was detached from the 28th Transportation Battalion and attached to the 106th on 10 September 1975. It moved to Karl Schurz Kaserne in Bremerhaven. The tractors or the TDA platoon were moved to Giessen, with the personnel assets reverting to the 37th Group TDA.

The task organization in late 1975 was:

- HHD, l06th, Ruesselsheim

- 1st Transportation Company, Nuernberg

- 69th Transportation Company, Bremerhaven

- 70th Transportation Company, G1essen

- 78th Transportation Company, Ruesse1sheim

- TTA. Ruesselsheim

- TTB. Bremerhaven

- TTD. Giessen

- TTH. Nuermberg

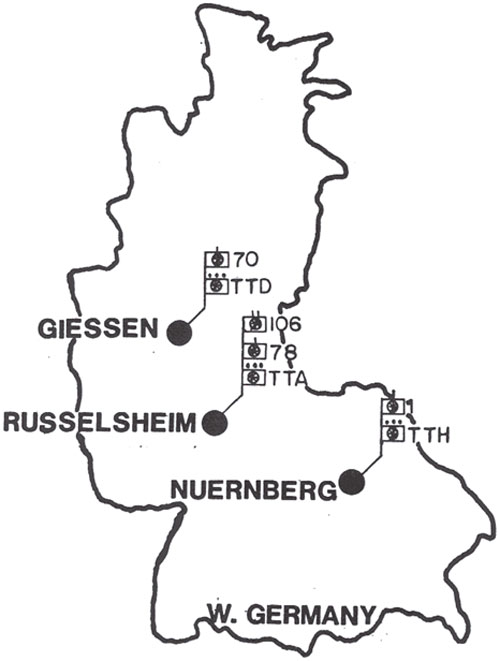

TASK ORGANIZATION 1972

ALOC ATTENTION SHIFT SOUTH: 1976 - 1978

By 1975, it had become painfully obvious Azbill Barracks was a terrible place for a trailer transfer point. It was located in a residential area far from the autobahn. It also had a very small trailer storage capacity. Detailed plans were drawn up for a move to Wiesbaden Air Base as USAF units were withdrawn as part of operation "Creek Swap." The plan had still not been executed by July of 1976. It is not clear if the exit move was ever made or if it was overtaken by events.

In January 1977, the Air Line of Communication (ALOC) test program began. It has continued to grow ever since to where it is now the battalion's most important task. There are two aerial ports in Germany which receive air cargo: Ramstein and Rhein Main Air Bases. ALOC cargo is predominantly repair parts (Class IX) and other high priority cargo delivered directly to a direct support unit. In November 1977, ALOC became a permanent DOD Program.

When ALOC was begun as a test program, the decision was made to establish a temporary TTP on Rhein Main to clear the arriving cargo. TTA moved from Bremerhaven to Rhein Main. This created a terrible facilities problem, from which the TTP still suffers. The TTP was established without construction of any facilities or hardstand to support the 200 plus trailers needed to provide daily support to ALOC.

By early 1978, the battalion's task organization was unchanged, except TTA had moved from Azbill Barracks, Russelshetm, to Rhein Main Air Base.

From 1978 through 1983 the battalion continued to develop, working the Trailer Transfer Point concept into a responsive and efficient transportation system throughout all of the Federal Republic. In 1983, the Trailer Transfer Points were given numerical designations.

The task organization in the fall of 1983 is as shown:

- HHD, 106th Transportation Battalion, Ruesselsheim

- 1st Transportation Company (Med), Nuernberg

- 69th Transportation Company (Med), Bremerhaven

- 70th Transportation Company (Med), (5 Squads Med, 1 Squad Mercedes, 1 Ton Vans), Giessen

- 15th Transportation Det (TTP), Rhein Main Air Base (Formerly TTA)

- 152nd Transportation Det (TTP), Nuernberg (Formerly TTH)

- 326th Transportation Det (TTP), Bremerhaven (Formerly TTB)

- 517th Transportation Det (TTP), G1essen (Formerly TTD)

The battalion's mission is, as always, to provide theater motor transportation service to USAREUR. The highest priority task is still port clearance. Although in 1983, the most important port was the Aerial Port of' Debarkation at Rhein Main Air Base. ALOC is the highest-priority, continuing program in the theater. Ninety-nine percent of' the loads originating at Rhein Main are priority one. The requirement is within 24 hours from the time of' receipt the battalion must deliver ALOC Cargo to its customer.

The MTHC Bremerhaven terminal continues to be a major customer, especially with the Army of the early 1980s in the midst of a fundamental program of equipment modernization. This program has brought about a sea change in workload. Workload in the early 1980's moved from merely very busy to nearly inundated.

The concept of trailer transfer points as pony express relay stations remains very similar to what it has been since 1950's. Each company now has an attached trailer transfer point. This is a significant additional tasking for each company commander.

One new wrinkle is battalion drivers receive TDY pay. In FY 82 the battalion TDY payments to drivers were over $565,000. Needless to say, this shifts a great financial burden from the soldier to the Government, where it belongs. The crushing emphasis on tons and miles was virtually eliminated during COL Ross' tenure as the TRANSCOM Commander. The policy has been continued by his successors, COL Lanzillo and COL Jack Piatak. There is still an enormous amount of work to be done, however. The battalion's four companies drove more than 7 million miles in FY 82 and more than 8 million in FY 83. This battalion's accident rate in mid-1983 was at its lowest ebb ever: 1.22 recordable accidents per million miles.

Since 1981, the 106th has had three overall priorities: becoming expert in the operation and maintenance of equipment; training; and assigned soldiers and their families. No matter what else was hot, the fire hose never shifted from these three fires.

The battalion places a great deal of emphasis on training, both individual and collective. Soldiers must know survival skills as well as primary MOS skills. The chain of command has not done its job if its soldiers cannot survive a night on the perimeter or a chemical attack. In the fall of 1981, a squad stand down program was begun. Each company stands down me squad for a week. The battalion directs at least one day be devoted to vehicular maintenance and one day to NBC operations. The rest of the week's training is determined by the company chain of command. All training is conducted by the squad leader.

During the 1981 Christmas holidays, the battalion headquarters moved back to its newly renovated building at Azbill Barracks in Ruesselsheim. In 1982, the battalion's strong maintenance program had a real chance to prove itself. In the USAREUR Excellence in Maintenance Competition, the 70th Transportation Company was the runner-up in V Corps and the 1st Transportation Company was the VII Corps winner. In July, 1982, the battalion represented TRANSCOM in the Nijmegen marches. Showing the "grunts" what truckers could do, the battalion team (under 1LT Keith Thurgood and SSG Dexter) placed 4th amongst USAERUR' s 52 teams

The battalion had a very strong showing during the Fiscal Year 82 Annual General Inspection (AGI). It continued to do well during 1983. So well, in fact, TRANSCOM paid the unit-the high compliment of canceling our FY 83 AGI.

The battalion's mission problem in the fall of 1983 was to continue feeding the ever hungry ALOC dragon. The program has been growing very rapidly since its inception.

During Operation Vital Link, Ramstein Air Base was closed from 1 May 1983 until 31 July 1983. This meant every ounce of air cargo arriving in the theater landed at Rhein Main and was cleared by the 106th. While the burden of the operation fell on the 78th Transportation Company, it was truly a battalion team effort. Shortly after Operation Vital Link was completed, the battalion received very heavy taskings for REFORGER 83. During the deployment phase the 106th was responsible for clearing both the Duesseldorf (69th) and Rhein Main (78th) APODs. In addition, the 70th Transportation Company was responsible for line haul from Giessen to the exercise area in the vicinity of Muenster. The battalion was solely responsible for all truck operations during the redeployment place. During September 1983, the battalion drove 801,507 miles. This was the most in any month since operation FRELOC in France in 1967.

During both Vital Link and REFORGER 83, the men and women of the battalion as they have so many times in the past, proved they could rise to any occasion and get the job done safely, on time, and in good order.

The year of 1984 brought numerous changes to the battalion both operationally, with the issuance of the new series M915A1 tractor, and in terms of unit changes of command, with the battalion receiving a new commander. Three of the battalion's four line haul companies received the new M915A1 Tractor as their primary task vehicle. The 1st Transportation Company, located in Nuernberg, kept the old series tractor due primarily to the excellent performance record their direct support maintenance unit enjoyed in reference to vehicle maintenance and responsiveness. Through Operation "Alley Cat" M915 tractors were swapped and convoyed to the 1st Transportation Company from the three other companies. The remainder of the old series tractors were turned in at depot. At the same time the 69th, 70th, and 78th Transportation Company received their compliments of the M915A1 series tractor.

On 26 June 1984, LTC Zikmund relinquished Battalion Command after three years to LTC Richard L. Fields. In Aug 84, after the 78th Transportation Company change of command between 1LT Sharon R. Duffy and CPT Deirdre L. Dillon, COL Ray Stearns, CDR, 37th Group, presented the 1st Annual Safety Trophy to the 106th for the safest battalion from July 83-Jun 84.

Operationally, the 70th Transportation Company successfully continued its unique theater Ammunition Mission, moving CAD's enroute to reaching 2 million accident free miles. As with the 70th, The CDR TRANSCOM, COL John Piatak, presented the 1st Transportation Company their award for 3 million accident tree miles. Along with this award the 1st Transportation was also presented the 106th Battalion's Safety Award for 1984. Additionally the 152nd Transportation Det (TTPH) received the 4th TRANSCOM's Maintenance Excellence Award (Light Category.) All companies successfully accomplished phased Army Training and Evaluation Program (ARTEP) prior to the year’s end.

Exercise REFORGER 84 challenged the 106th and each of its companies from Aug - Nov. Held in Northern Germany, the exercise tested the battalion's ability to pull together and successfully operate as a team. As the battalion began implementation its Annual "Christmas Mail" mission, 1984 closed out with new challenges and another REFORGER Exercise to deal with. January 1985 brought REFORGER 85, the termination of "Christmas Mail" and planning for Wintex 85. All missions which were handled professionally and responsively. Back to back REFORGER exercises truly tested the transportation network in USAREUR. The 106th Transportation Battalion played an integral part in the successes of each. Centered in Giessen, REFORGER 85 cargo commitments were placed directly on the 70th Transportation Company and the 517th Transportation Detachment. Meeting the challenge, the 70th Transportation Company reached 3.5 million accident free miles and was subsequently nominated from the battalion as 37th Transportation Group's Company of the Year.

In March 85, the battalion began its normal training cycle. The 1st Transportation Company successfully planned and executed the first Military Operations in Urban Terrain (MOUT) ARTEP in 4 years in the German city of Langenzenn. Deployment of the 152nd Transportation Detachment on their first ARTEP marked a first. Each company, through an innovation phased ARTEP program planned and executed individual exercises using MILES equipment for realism and training. The strict coordination of mission requirements ensured the battalion’s theater mission was accomplished.

Another innovative training change implemented in 1985 was the 4th platoon concept of Army Motor Vehicle Instructors (AMVI's) who were responsible for training newly assigned 64C's upon graduation from the Primus Driver's Academy. This concept centralized training in one platoon, enhancing it and more effectively utilized training time to ensure qualified drivers in less time. To date this concept has been totally successful with proven results in better qualified and safer, more professional drivers.

All companies changed command during 1985. This change in leadership established a new group of leaders destined to meet the challenges offered only to commanders within the 106th Transportation Battalion.

Safety wise, the 69th's new commander CPT Steven Kerr, inherited a company which broke the 1,000,000 mile accident free miles driven within his first five days of command.

In training, 1985 found the 69th Transportation Company led by 1LT Doug McKay, representing the 37th Transportation Group in the Nijmegan marches in Holland. It was again proven Transporters could successfully compete with the Army's ground pounders. Successful Berlin Convoys were conducted by the 69th, 70th, and 1st Transportation Companies throughout the year. Each exercise ensured the surface corridor remained open for Allied traffic in addition to rewarding selected soldiers with a well deserved, unforgettable visit to the island city. Additional new equipment was issued to the European theater. In addition to the requirement to deliver most new vehicles to depots for further deployment, the 106th, itself, received the new CUCV, Which replaced the Army's standard-the jeep. The Group's trailer fleet was updated with the M872A3 trailer and the conversion of drop-side trailers which increased the trailer fleet's productivity. Trailer Transfer Points were issued 6,000 and 10,000 pound forklifts for trans-loading cargo. Sponsoring the 37th Group's Annual Truck Rodeo, the 106th ensured it was the best organized competition ever and then in turn brought home top honors.

International partnership activities saw the battalion participate with the Dutch in the Queen's Birthday Ball and a separate sports day competition. The 105th Royal Transportation Battalion was an idea host for all the activities. Thanksgiving saw local German neighbors of Azbill Barracks in Ruesselsheim invited to share with the soldiers of as a gesture of appreciation for continued relations and good will.

REFORGER 86, centered in the Nuernberg area, ushered in 1986 and as in REFORGER 85 with the 70th Transportation Company, multiplied the work load for the 1st Transportation Company and the 152nd Transportation Detachment. An unseasonably warm winter turned the exercise into a major Command Post Exercise (CPX), but the 106th Transportation Battalion again forged together to meet the challenges through safe and responsive cargo delivery and mission accomplishment.

Training again took center stage after ENDEX and the 1st Transportation Company conducted their now routine MOUT ARTEP. The 78th ran the Berlin Convoy for February 86 coupled with a totally female Convoy making the Brunson Mail Run to Belgium. Both were excellent training opportunities to show the US Transportation Corps to international customers. The issuance of LOGMARS equipment brought the automated world of metal bar code plates and an innovation cargo documentation/accountability system for military Cargo. The system will offer maximum benefits once it becomes totally operational. Another unique milestone for the 78th Transportation Company came on 14 February, when it hit the 1,000,000 accident free miles driven mark. The remarkable thing about this achievement is due to its unique mission, the 78th hit the one million mark 15 miles at a time. As in 1984, 1986 saw the Battalion and two of its companies change command.

On 26 June, LTC Richard L. Fields relinquished battalion command after two productive years to LTC Glynne R. Hamrick. Within 30 days of assuming command, LTC Hamrick received the same award LTC Fields received during his first days of command - namely the 37th Group's Safety Trophy as the Safest Battalion from July 1985 - June 1986. It marked the 2d time out of 3 years the 106th boasted the safest miles driven in 37th Transportation Group. Two of the battalion's companies continued their safe driving mileage records throughout 1986 - the 1st Transportation Company and the 69th Transportation Company both broke the 3,000,000 mile mark.

CAPSTONE training and interface with the reserves marked 1986 as a banner new year for new realignment and detailed coordination with soldiers and units from CONUS. The basic ground work performed during 1986 marked the future a challenging and demanding test for transition to war and basic Battle Book operational planning.

Heightened terrorist activities throughout Europe caused the cancellation of nearly all partnership and German - American activities. Inspite of the threat, one new program initiated in May 1985 made it possible for Azbill Barracks to adopt a local village - Bauschheim. Activities planned included the local mayor and installation commander with representation of both organizations enjoying the traditions and camaraderie of each. A close relationship and pistol range firing with the Ruesselsheim police department also began during the summer of 1986. With the end of FY 86 came planning and preparation for "Christmas Mail 87". The 106th stood ready to meet its greatest operational challenge yet.

FORT CAMPBELL, KENTUCKY

Following the downsizing and reorganization of the US Army in the early 1990s, the 106th Battalion was inactivated on 15 September 1993. It was then reactivated at Fort Campbell, Kentucky on 18 September 1998, where it became a part of the 101st Corps Support Group, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault). The 1st Medium Truck Company and the 15th Trailer Transfer Detachment were transferred to the 53rd Battalion, the only theater level transportation truck battalion to remain in Europe. At the same time, the 69th, 70th and 78th Medium Truck Companies were inactivated. Because the 69th and 70th were two of the oldest truck companies in Germany their guidons were transferred to the 28th Battalion to reflag two of their companies.

While at Fort Campbell, the 106th Battalion picked up control of the following companies:

- 372nd Transportation Company (Terminal Transfer

- 541st Medium Truck Company (POL)

- 494th Light-Medium Truck Company

After Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld took office, in 2001, he wanted to streamline the Armed Forces and particularly the US Army by reducing the “logistical foot print.” At the same time Army chief of Staff General Shinseki wanted to organize more Special Brigade Combat Teams built around the new Infantry Tactical Fighting Vehicle. Someone would have to pay the bill for the cuts and new programs. The Department of the Army level decision directed US Forces Command to identify which units to inactivate. USFORSCOM based their recommendation on installation support, readiness, OPLAN support and “Kentucky Windage” to determine which units to inactivate. In 2002, they identified the units to inactivate. The 53rd Movement Control Battalion (MCB) at Fort McPhearson, Georgia, the 57th Transportation Battalion at Fort Lewis, Washington, and the 106th Transportation Battalion at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, were designated for inactivation as a result of Total Army Analysis 2009 (TAA-09) results. The US Army would go to war the next year realize its error in reducing transportation units. In fact, two of the three battalions slated for inactivation would deploy.

OPERATION IRAQI FREEDOM 1

In July 2002, USCENTCOM sponsored Operation VIGILANT HAMMER from 10 to 31 July. The 7th Transportation Group wanted to download one Large, Medium Speed, Roll-on, Roll-off (LMSR) vessel, the Lotkins, from the Afloat Preposition Stock (APS) 3 at Port of Au Shuyabah in order to determine the download time and also how many Prepo vessels they could berth at the pier at one time. The planners of the transportation commands spent one day watching the download then loaded up in two buses and visited Camp Arifjan, which was still under construction, and the location of where the other staging camps would be. All were just empty spaces in the desert. MAJ Thomas Jones, 6th Battalion S-3, brought his operations sergeant, SFC Michael Aguilar. MAJ Craig Czak, 106th Battalion S-3, brought his operation sergeant, SFC David Munsey. MAJ Thomas Jones, 6th Battalion S-3, brought his operations sergeant, SFC Michael Aguilar, because of his institutional knowledge of the battalion.

At that time, no one had determined which truck battalion would extend the line of communication into Iraq. Since the 106th Battalion did not belong to the 7th Group, MAJ Czak believed that they would answer directly to the 143rd TRANSCOM. They thought that they would receive the mission to cross into Iraq. LTC Helmick was confident that his 6th Battalion would get the mission because the 143rd TRANSCOM and the 7th Group had a long established working relationship. On the last day of the planning conference, the transportation planners met at CFLCC headquarters. There MG David E. Kratzer, Commander of the 377th TSC, thanked everyone for coming then reassured them that they were going to war. From then on, the battalions made serious preparations for war. The problem was that the Army had identified three transportation battalion headquarters for inactivation and the 106th Battalion was one of them. As the clock clicked closer to going to war, so was time running out for the 106th.

The 106th Battalion, commanded by LTC Randolph “Randy” Patterson, received its deployment order during the second week in January 2003. Because of snow, the personnel of the HHD and 594th Transportation Company did not deploy from their home station until 15 January. Like the 6th Battalion, it was multifunctional transportation battalion but would operate as a pure truck battalion. Therefore, it would only take its organic 594th Medium Truck Company. After a 22-hour flight, they arrived at Kuwait International Airport (KIAP). The 6th and 106th Truck Battalions fell under the control of the 7th Transportation Group as theater movement assets. The original plan had the 106th establish its headquarters at the Port of Shuyabah, but the 7th Group changed their initial destination to warehouse in Camp Arifjan. They had rail loaded their equipment in December to sail by ship. It arrived in the third week, 26 January. The rest of HHD and its equipment followed on a C-5 in early February, a month after the 89th Medium Truck of the 6th Battalion. The initial mission of the theater trucks was to conduct Reception Staging and Onward Movement and Integration (RSO&I) of arriving units.

The original plan for the 106th Battalion in the OPLAN was port clearance and supervision of host nation trucks. However, the host nation assets were not ready by the first of February and the need for trucks exceeded the capability of the 6th Battalion. MAJ Craig Czak, 106th Battalion S-3, asked COL Jim Veditz, Commander of the 7th Group, to sign over part of the trucks for the 89th TC so his battalion could assist in the RSO mission. MAJ Thomas Jones, 6th Battalion S-3, told Czak, “No way in hell are we going to give you our trucks. We’ll let you right seat ride with us.” Within 36 hours of its arrival, the 594th TC, under the command of CPT Aaron Wolfe, started training up their drivers by having them ride right seat driver with the trucks of the 89th Transportation Company of the 6th Transportation Battalion. The 106th Battalion was eager to get to work. MAJ Jones suggested that Czak sign some trucks from Prepo. Czak asked the 7th Group for permission to draw the Prepo trucks and equipment of the 513th Transportation Company that would arrive later and belong to the 106th Battalion. Since the 513th TC would belong to the 106th Battalion when it arrived, this caused no conflict and the equipment would be ready and waiting for them. COL Veditz agreed and after a week in Kuwait, BG Vincent Boles, the AMC commander of Army Preposition Stocks (APS) 3, gave them permission to sign for the Prepo. The 594th TC then joined in on the 7th Group’s RSO&I mission.

Unlike the 6th Battalion, MAJ Craig Czak, the 106th Battalion S-3, felt that they could put more trucks on the road and get in more “flips” by running 24-hour operations in three shifts. One platoon would be on the road, another in maintenance and another resting. The 106th Battalion were treated like redheaded step children in the 101st Airborne Division at Fort Campbell so they were very competitive by nature. The 594th also had more of its drivers licensed than the 89th Medium Truck so it completed more missions each day. Wolfe also encouraged friendly competition within his company. It became a competition between platoons as to which one could get in more flips.

The medium trucks hauled Class I (food and water) from the Port of Swuayk to TAA NEW JERSEY, VIRGINIA, NEW YORK, PENNSYLVANIA, COYOTE, FOX, Udari and Arifjan. The medium trucks also moved Class V (ammunition)from the Ammunition Supply Point at KNB to Ali Al Salam Airbase, Al Jabber Airbase, Camps Udari, Arifjan, COMMANDO, NEW YORK, NEW JERSEY, FOX, COYOTE and Breach Point West. They delivered Classes II, IV, VII and IX to the various bases.

By the early part of February, 30 to 50 Host Nation truck assets were available. By the first week in March they had 200 trucks. The Host Nation trucks moved cargo from the TDC to the camps.

The 106th Battalion, like the 6th Battalion, picked up several more truck companies from other units. The 513th Medium Truck, commanded by CPT Nicole Humpheries, arrived from Fort Lewis, Washington. The 109th Medium Truck, commanded by CPT Todd Terrell, came from Mannheim, Germany. The 126th PLS, commanded by CPT Dennis Major; and the 483rd TTD, commanded by 1LT Chris Rogers, came from Fort Bragg, North Carolina. The 106th Battalion sent a platoon of the 126th PLS to carry the pipeline for the construction of the IPDS pipeline from Camp VIRGINIA to Breach point West.

The 233rd HET, commanded by CPT Larry House, arrived from Fort Knox, Kentucky, by mid-February and drew Prepo. Since there were only two HET companies in 7th Group, they moved heavy equipment from the SPOD and APOD to Camps Doha, Arifjan, Udari, NEW JERSEY, VIRGINIA, NEW YORK, PENNSYLVANIA, COYOTE, FOX and VICTORY.

They also picked up the 567th Transportation Company from Fort Eustis, Virginia. The 106th Battalion received the 68th Medium Truck Company, commanded by CPT Edward J. Gawlik III, arrived from the 28th Battalion in Germany on 4 March and drew all its equipment by mid-March. On 19 March, they also received the 109th Transportation Company, commanded by CPT Todd Terrell, from the 28th Battalion in Germany.

During the planning for the invasion of Iraq, the 7th Group would extend the supply line from Kuwait up to the V Corps rear boundary as it advanced toward Baghdad. The 106th Battalion already had the responsibility for supervising the host nation trucks. Veditz assigned it the mission to establish the Convoy Support Center (CSC) NAVISTAR on the Kuwait/Iraq border. They also received the responsibility for the Theater Distribution Center and would push supplies from there up to NAVISTAR. The 6th Transportation Battalion would cross the border into Iraq and establish LSA ADDER where they would run a pull-push operation. Their trucks would run back to CSC NAVISTAR then push cargo up to V Corps rear, initially at BUSHMASTER. The plan called for the trucks of the 106th Battalion to stop at the Iraq border. Veditz gave Randy Patterson the arriving 494th Light/Medium Truck, 1454th and 1168th PLS Companies. Patterson already had the 126th PLS, the 513th and 594th Medium Truck, the 233rd HET, and his battalion would then total over 400 trucks in nine companies. The 1454th PLS, commanded by CPT William McCormick, arrived at the end of February. The plan also had the 32nd Transportation Group relieve the 106th Battalion when it came available and the 106th would jump forward of ADDER. Patterson had the 494th Medium Truck for two weeks before he attached it to the 101st Airborne Division on G-Day.

Patterson looked at his map of the balloon that encompassed NAVISTAR. It was off of MSR TAMPA, right along the border with Iraq. He liked the idea of setting up just north of the border town of Safwan, but could not cross to border to reconnoiter it. Marines owned the area. The 106th Battalion’s mission was to send 66 trucks with supplies up to the 6th Battalion at Tallil on G+3.

On 16 March, the 106th Battalion assumed command and control of the Theater Distribution Center (TDC) from the 11th Battalion and command and control of the Host Nation Vehicle Contract. Transportation units continued to move 3rd Infantry Division and 1st MEF to their staging areas near the border. Patterson assigned the 1168th Medium Truck to the TDC to make up the short comings of the Host Nation trucks. The Host Nation truck drivers would disappear for up to three days. Sometimes the drivers would drop off a load one day, then sleep for another day before returning the next day. Sometimes the units at the camps shanghaied the trucks. Patterson had the 1168th draw HMMWVs to escort the Host Nation trucks so that they would return on time.

On Monday, 17 March, Bush announced his ultimatum to Saddam Hussein. Bush gave Hussein 48 hours to leave Iraq with his entire family. That day, the 7th Group received a message from the 143rd TRANSCOM. It originated from CENTCOM 17 minutes earlier directing the 106th Battalion to occupy the UN compound as NAVISTAR. CW3 Michael Wichterman, in the Group S-3, realized that each headquarters had just passed it down without thinking through the consequences. He sent the email back up the CFLCC to verify if they could legally do that. Meanwhile he sent an email to LTC Patterson to go and check the compound out. LTC Patterson took MAJ Czak and CPT Chris Kirkman, Battle Captain, in his recon party. They spent four hours looking around. The 106th Battalion had to establish a control point and a TTP. Patterson needed a place to park convoys and provide security. This was his first visit to the site. He found an abandoned, UN compound that had buildings in a fenced-in compound. They asked a Kuwaiti Air Force colonel and retired general for permission to occupy it. The Kuwaitis told them they could have it.

On 20 March, the day of the ground assault, the 106th Battalion relinquished responsibility of the TDC over to the 406th Transportation Battalion of the 32nd Transportation Group. After the Marines vacated their camp on the border, the 106th Battalion “Jump” TOC and 594th Medium Truck Company arrived at 1830 on 22 March. Patterson’s NCOs started working on getting the water and electricity running. He established a 66-acre TTP motor pool. KBR contract engineers mixed clay, sand and gravel, wetted it and rolled it flat then sprayed a coating of oil to seal it. Anything up to including HETs could drive on it. As long as they kept oil sprayed on it, the vehicles would not break the seal and create pot holes. CSC NAVISTAR became the last US compound along MSR TAMPA before crossing into Iraq. MSR TAMPA led to CEDAR and VIPER.

The 106th Battalion had the task to send 66 trucks with the Marines and 3rd ID (M). The battalion headquarters only had one map that they had borrowed from the 6th Battalion. From this the staff drew strip maps for the drivers. CPT Wolfe tasked 2LT Erin Cornett and SFC Crader, of the 594th Medium Truck, to take a convoy with the 3rd ID (M) and 2LT Kathryn Mills to take a convoy up to VIPER with the Marines. She asked 2LT Sarah Parker, also of the 594th, if she wanted ride along. Parker did. Mills took a little more than 30 trucks up to Camp COYOTE around 0600 in the morning of 23 March to pick up the palletized loads of ammunition. She did not have a map of the area nor did she have MTS, only a commercial GPS that was not very accurate. The convoy was supposed to move up MSR TAMPA, which was a straight drive to VIPER. While at COYOTE, someone called over to inform Mill’s convoy that they could not drive on MSR TAMPA but had to use ASPEN. Early that afternoon, they fueled up the trucks and were ready to go. The Marines had several sections of maps and led them to Camp YOYO, which then stood for “You’re On Your Own.” Evidently, someone named the stopping point after the ADDER packages has passed.

Mills’ convoy finally found Breach Point West in the dark. Mills had no idea of whether she had crossed the border. Someone who provided fuel for the Marine HMMWVs informed her that she would know when she reached the border because she would see a Movement Control Team. She drove further and saw neither the MCT nor any MPs. She called back to the battalion headquarters and said, “It’s pitch dark. I don’t even know if I’m in Iraq yet or not. Can I park this convoy at Camp YOYO until daylight, and then move on in the morning, when I can see what’s going on?” They did not have any night vision devices. Battalion informed her, “No, that ammo needs to go now.” She said, “All right.” They finally figured out where they were and it turned out that they were two kilometers off from where the GPS said they were. 12 hours after leaving COYOTE, her convoy reached VIPER at around daylight in the morning of 24 March. VIPER was nothing more than a bunch of tents at that time with no berm for security. Mills’ convoy was the first convoy of the 106th Battalion to cross into Iraq. Cornett took his convoy with the 3rd ID (M) up beyond An Nasariyah and remained gone for 8 to 9 days.

MAJ Czak sent CPT Chris Kirkman up to VIPER to look for Mills’ convoy. It took him three hours to reach VIER and find them. They were waiting for the Marines to bring up the forklifts to unload them. The convoy was out of fuel, so Kirkman drove around and located a fuel tanker about four miles in the desert. He assumed that they were lost. They had about 1,200 gallons left in their 5,000 gallon tanks. After filling up the trucks, Kirkman then escorted the convoy back down TAMPA to NAVISTAR that night. They arrived around 0500 the morning of 25 March. Mills and Parker moved into tents, but no one had brought up Mills gear. She later drove back to pick up a couple of trucks and trailers from maintenance in Arifjan and brought back her personal gear.

The 106th Battalion established split based operations. Patterson and his S-3, MAJ Czak, ran the convoy support center at NAVISTAR with the 126th PLS and 594th Medium Truck Companies. The 567th CTC (-) ran the TTP. The 171st and 259th Movement Control Teams of the 53rd MCB provided movement control. The battalion XO ran RSO mission out of Arifjan. He had the vast majority of truck companies: 233rd HET, 513th and 1454th Medium Truck Companies.

On 25 March, the 106th Battalion finally received the 171st MCT form Fort Irwin, California, and on 29 March, would receive the 259th MCT from Fort Bragg, North Carolina. The MCTs unfortunately had no communications. NAVSITAR did have a phone line running within 72 hours after the 106th Battalion had arrived, but they had no email capability for 45 days.

Czak tried to schedule the convoys from Kuwait so that they would arrive at NAVISTAR at night. Either he or 1LT Kirkman would brief the convoy commander on the mission and enemy situation. The convoy would rest overnight then depart the next morning. During the early part of the war, convoys could only drive during daylight hours in Iraq. From NAVISTAR, convoy supporting V Corps drove to CEDAR and those supporting the 1st MEF drove to VIPER.

On 26 March, the day after the mother of all stand storms, LTC Patterson and MAJ Czak drove up to CEDAR. COL Veditz was irritated that they had come up without his permission. They told him that they could not get him on the radio. This was the problem of Veditz remaining forward of his subordinate units. They had good communications with the 7th Group Rear at Arifjan but had to relay messages through them to Veditz. Due to communication limitations, only the 6th Battalion could talk with him. This made the 11th and 24th Battalion very happy, but not the 106th Battalion. With Stultz forward, Helmick pretty much took his direction straight from his theater transportation commander, not Group.

The two officers of the 106th Battalion met with LTC Helmick to discuss operations. Helmick had a functioning TTP at CEDAR. He did not believe that his tractors need to drive back to NAVISTAR to pick up trailers. Both truck commanders agreed that the 6th Battalion should get out of the pull business and the 106th Battalion convoys should push to CEDAR. The 106th Battalion would finally get to cross into Iraq and push cargo to CEDAR. There was still an air of friendly competition. Czak told Helmick that the 106th Battalion was deliberately holding back on mission so as not to overload the 6th Battalion. Helmick leaned back and put his hand behind his head and told the major, “Bring it on.” Czak accepted the challenge and was not content to just push supplies forward, he wanted to shove more trucks into CEDAR than Helmick could handle. He wanted to overwhelm the 6th Battalion and create a bottleneck. This kind of friendly competition would benefit the customers up the road.

Since Helmick no longer needed to haul heavy equipment, he turned the 96th HET Company over to the 106th Battalion on 30 March. He kept 2LT Delima’s platoon of HETs to move his KALMARs around since the 551st only had two organic HETs. They would also conduct recovery operations of other units’ heavy equipment. The two HET companies then went back to Arifjan to move the heavy equipment of the arriving 4th ID(M). In the spirit of cooperation, Patterson gave Helmick the 68th Medium Truck Company on 3 April. This brought the 6th Battalion up to four truck companies: the 68th and 89th Medium Truck Companies and the 15th PLS Company.

The 32nd Transportation Group would replace the 7th Group and eventually receive more trucks. It would organize them under three truck battalions instead of 7th Group’s two. The 346th Transportation Battalion (Motor) (USAR), out of Roosevelt Roads, Puerto Rico, would replace the 6th Battalion in Iraq and the 495th Transportation Battalion (Motor) (NG), from Kalispell, Montana, would replace the 106th Battalion at Camp NAVISTAR on the border. The 32nd Group would also pick up the 419th Transportation Battalion (USAR) out of Bartonville, Illinois. It would supervise the commercial contract trucks and the Theater Distribution Center (TDC).

The camp outside the United Nations compound was well on its way to completion anyway. Engineers had mixed sand, clay and gravel with a wet oil solution to form a hard pack that could support the weight of HETs. This 66-acre parking lot transformed into their trailer transfer point and motor pool. Patterson did regret losing the fine dining facility and having to move everything and everyone into tents though. By the middle of June, none the less, the new camp sported a dining facility that could seat 400 with running water, showers, fixed latrines and air conditioning in all tents. For recreation, they had built tennis, basketball and volley ball courts. They dubbed their new camp, NAVISTAR Oasis.

In late April, the 377th Theater Support Command instructed the 106th Battalion to move out of the United Nations Compound so that United Nations personnel could return. However, after the declaration of victory on 1 May, the United Nations did not return. None the less, the 106th had only expected to benefit from its fixed facilities until they had constructed their own camp outside the fence. This decision did not bother LTC Patterson much, since the 495th Transportation Battalion was replacing his battalion at NAVISTAR and he was in the process of jumping his battalion forward to CEDAR to replace the 6th Battalion as it relocated to Gharma. Patterson had brought the rest of the battalion forward to NAVISTAR to prepare for the jump forward. By Memorial Day, at the end of May, he had his entire battalion in one location for the first time.

With the 495th Transportation Battalion in place, the 106th Battalion was the last of 7th Group’s battalions to depart. The battalion had proudly driven 5,121,320 miles, hauled 467,870 tons of cargo and 49,980 pieces of equipment. It brought its companies back to clean their equipment and put it back in storage. As Patterson’s companies prepared to go home the word came down that National Guard and US Army Reserve units would have to stay. Patterson had to leave the 1454th Medium Truck Company. It hurt to leave companies behind that had done the same thing they had. Telling them that they had to stay was not as bad as telling the 109th, which was an active duty company from Germany. They unfortunately had been mission capable since March and had already cleaned their equipment and turned it in. Patterson had the unpleasant duty to inform them, “Unpack your stuff, you’re going to stay.” It was very demoralizing to come that close to going home then told they could not go. HHD, 106th Battalion redeployed on 12 July 2003 and just narrowly escaped being stuck there too. Just after its arrival at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, the DA decision came down that all units in theater would remain in theater. Had HHD delayed just 15 days, they would also have been extended.

OPERATION IRAQI FREEDOM 04-06

The war had only given the 106th Transportation Battalion a stay in execution, after it returned to Fort Campbell, the Battalion was once again put on the chopping block and this time the Army was serious. The unit headquarters was zeroed out on staff as it drew down to inactivate. Again the life expectancy of the 106th was extended but this time the battalion headquarters had to be resuscitated. In May 2004, HHD 106th Battalion received orders to deploy to the CENTCOM Area of Operations again. The headquarters would have to be built up with personnel from scratch and was slated to deploy once again to Kuwait. For that reason, a number of officers on the command list turned down the opportunity to command the battalion. LTC James Sagen was offered command and accepted on 21 June, arrived on 18 July and assumed command on 4 August 2004. The battalion deployed thereafter to Kuwait shortly on 24 September and coincidently was assigned to NAVISTAR, a camp built by the 106th during OIF1. The 106th Battalion again fell under the command of the 7th Transportation Group and on 15 October the 106th completed the Transfer of Authority (TOA) with the 812th Transportation Battalion and inherited the following medium truck companies:

- 172nd Medium Truck (NG NB)

- 227th Medium Truck (NG NC)

- 518th Combat Gun Truck Company (Provisional)

- 1450th Medium Truck (USAR)

- 1486th Medium Truck (USAR)

- 1487th Medium Truck (USAR)