The Trains Stop At Tampa: Port Mobilization During the Spanish-American War and the Evolution of Army Deployment Operations

BY Stephen T. Messenger

American History No. 104 (Summer 2017)

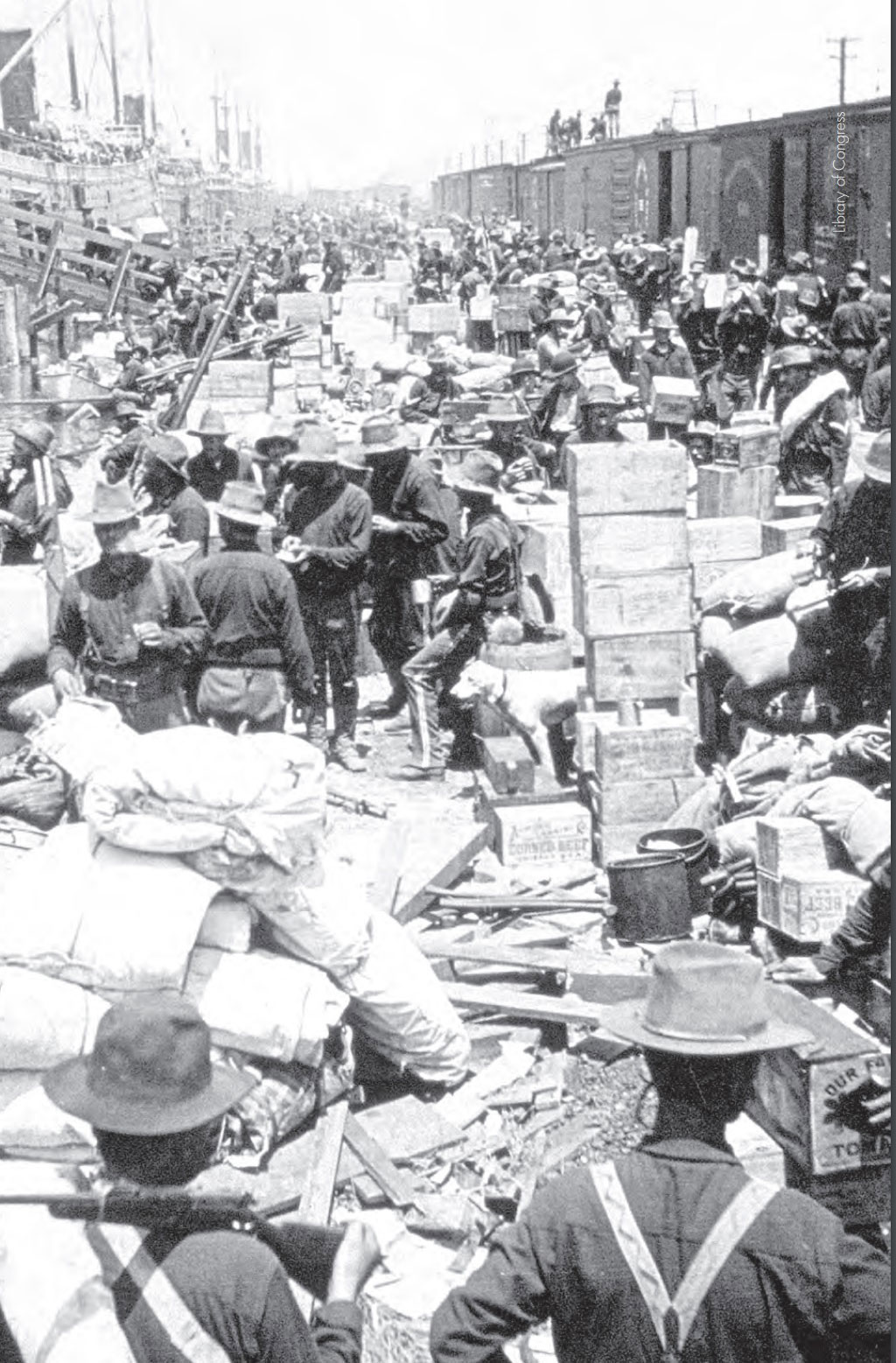

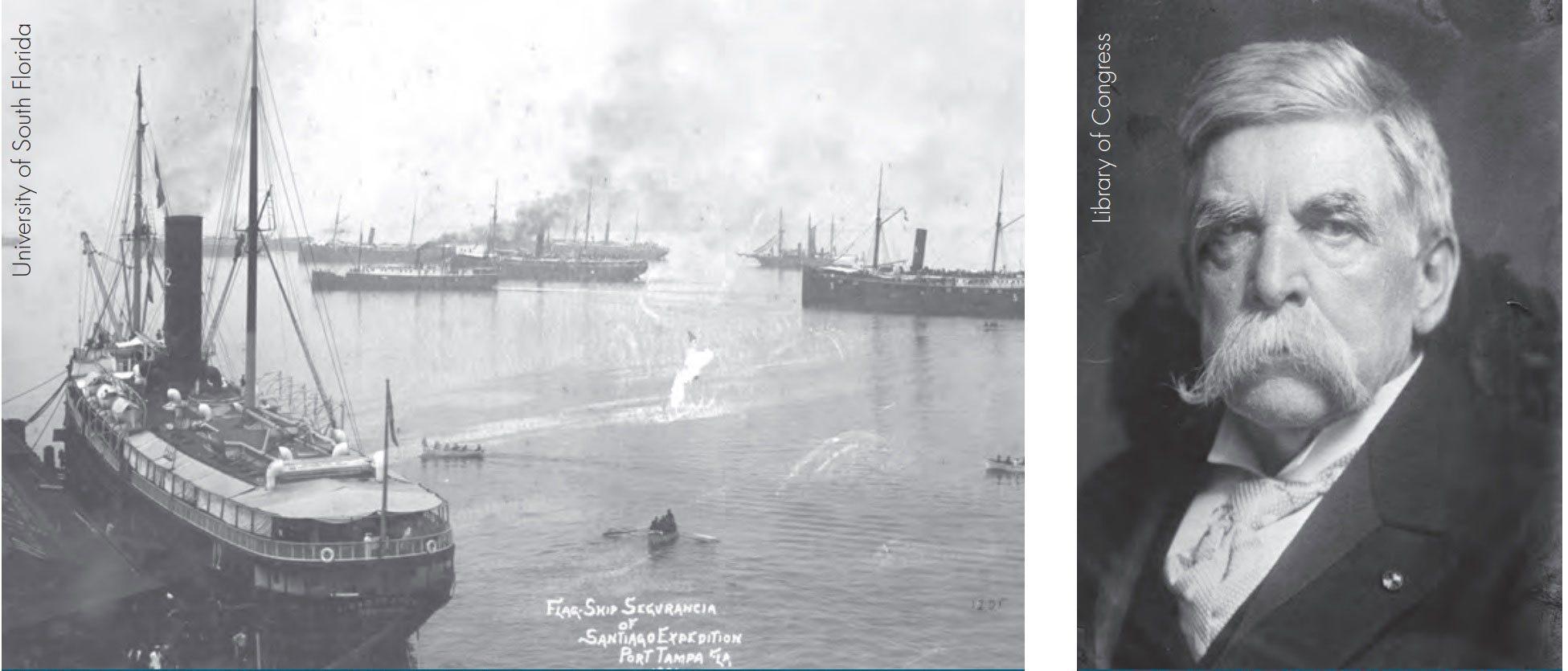

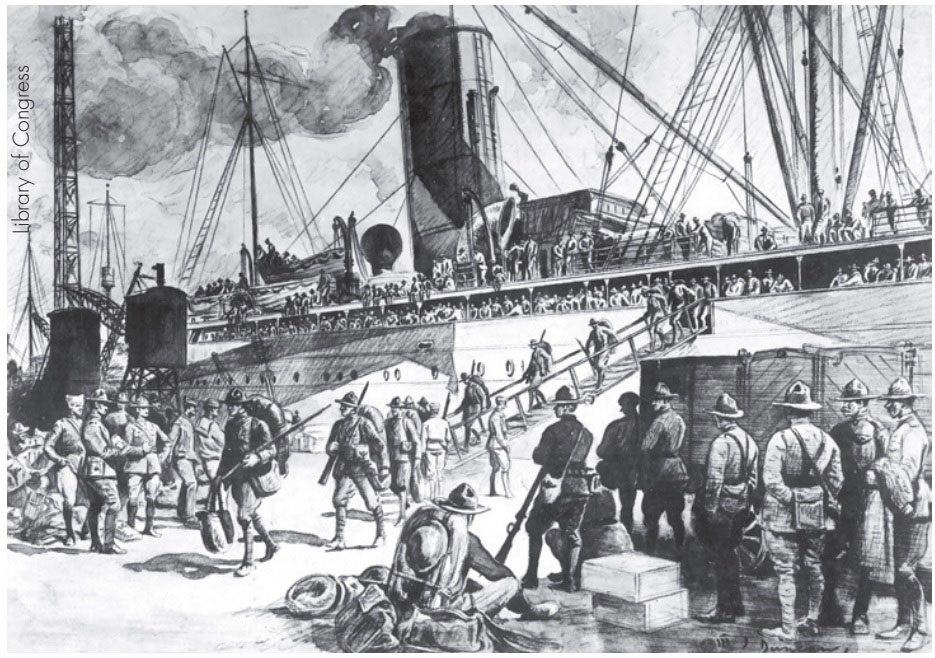

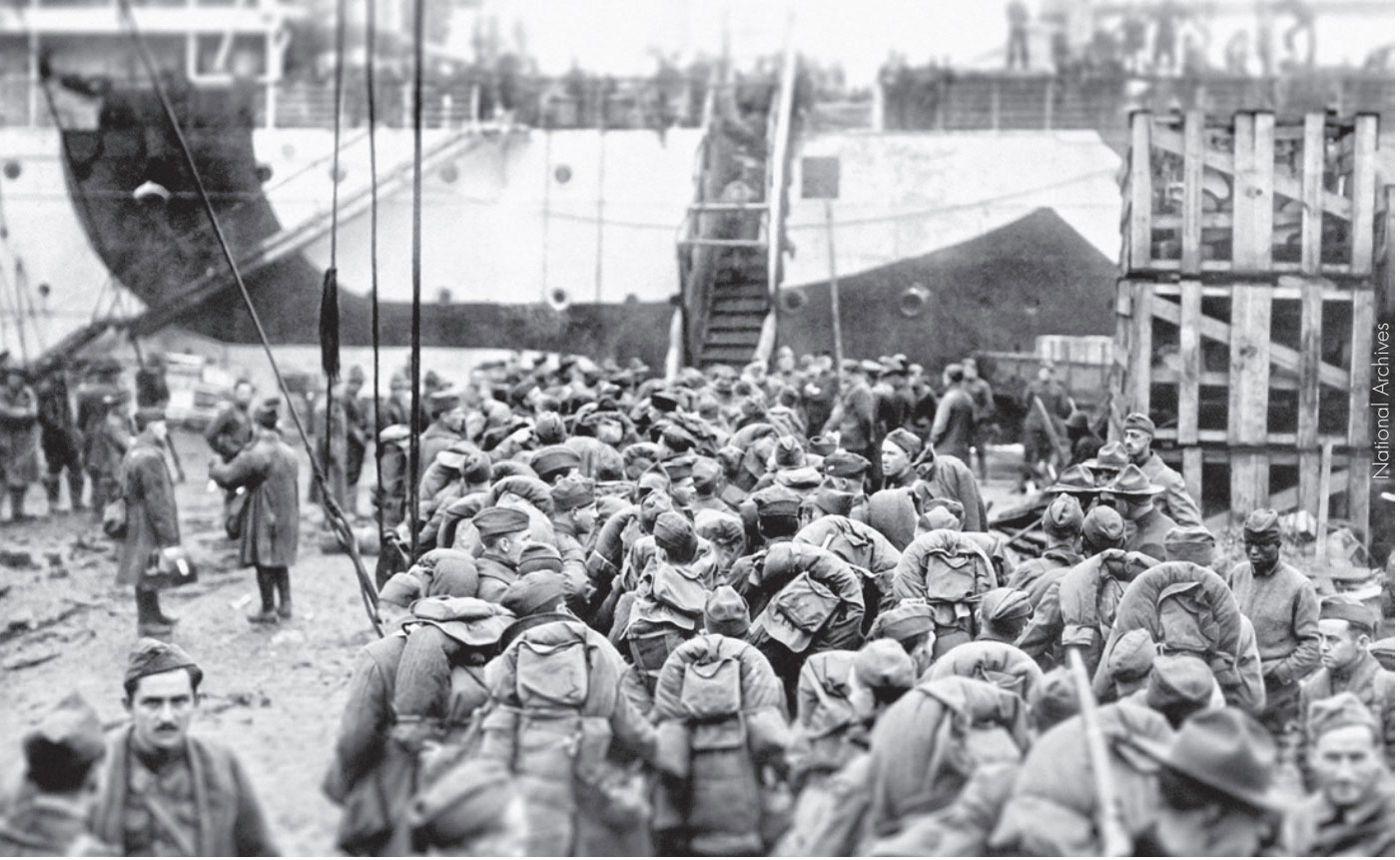

Loading transport ships in Tampa, Florida, bound for Santiago, Cuba

The American entry into World War I presented its military logistical planners with what must have seemed like an insurmountable problem. The scale and scope of World War I logistics operations was unfathomable at the time. The United States was eventually able to mobilize massive numbers of troops and materiel throughout the war, which contributed tremendously to the Allied victory. However, two decades earlier, another American expeditionary force met with very little success in deploying overseas. In the Spanish-American War, the United States mobilized soldiers destined for Cuba from a seldom used and little-known port in Florida called Tampa. The unsuccessful efforts at mobilizing a mere 25,000 troops highlighted a broken system that, following logistical evolution and improved methodology, led to successful World War I deployments less than twenty years later. The knowledge gained during the Tampa mobilization created the foundation of current Army deployment doctrine.

Port Mobilization During the Spanish-American War and the Evolution of Army Deployment Operations

The U.S. Army and Navy staged men and equipment in Tampa to prepare for the 1898 invasion of Cuba. The services conducted what planners today call the “deployment process.” This small scale mobilization was the first foreign expeditionary operation conducted by the Army since the Mexican American War in 1847. Critical to the Tampa operation was the application of establishing basing, maintaining tempo, and extending what the Army now calls operational reach, “the distance and duration across which a joint force can successfully employ military capabilities.”1

The evolution of the Army deployment process demonstrates the significance of the lessons learned from the force’s time in Tampa. The experience gained during the preparations for the invasion of Cuba in 1898 improved future operations and equipped the United States to move troops and materiel quickly and efficiently. The skills developed in Tampa enlightened mobilization planners and enabled them to establish processes to receive, stage, and deploy units and equipment in a more efficient manner using the principles of unity of command, synchronization, unit integrity, and balance.2

History of the Santiago Expedition

Cuba had been a Spanish colony since Christopher Columbus claimed it in the names of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella in 1492. By the late nineteenth century, however, Cuban independence was on the minds of many of the island’s inhabitants. The Cuban insurrection against its Spanish colonial master began on 28 February 1895, although there had been indicators of an impending Composite Image: Soldiers with the 21st Infantry cook a meal next to boxcars on a siding in Tampa, 1898. Military History Institute Port Mobilization During the Spanish-American War and the Evolution of Army Deployment Operations This content downloaded from 132.159.80.40 on Wed, 20 Dec 2023 14:03:01 +00:00 All use subject to https: 36 Army History Summer 2017 insurgency as early as the 1850s. Numerous nonviolent efforts by the Cubans to gain independence from Spanish authority had repeatedly failed. However, political efforts drew in private American support for the rebels.3

The Spanish reacted by using military force to establish reconcentration camps for 300,000 Cubans beginning in 1896. With the insurgency growing larger, Spain attempted to solve the problem by agreeing to limited political autonomy in November 1897, but the revolutionaries declined the offer and sought complete independence. The United States, concerned with trade disruption, protested through diplomatic channels. American officials cited human rights violations, but the Cuban people received no respite from Spanish aggression and retributions.4

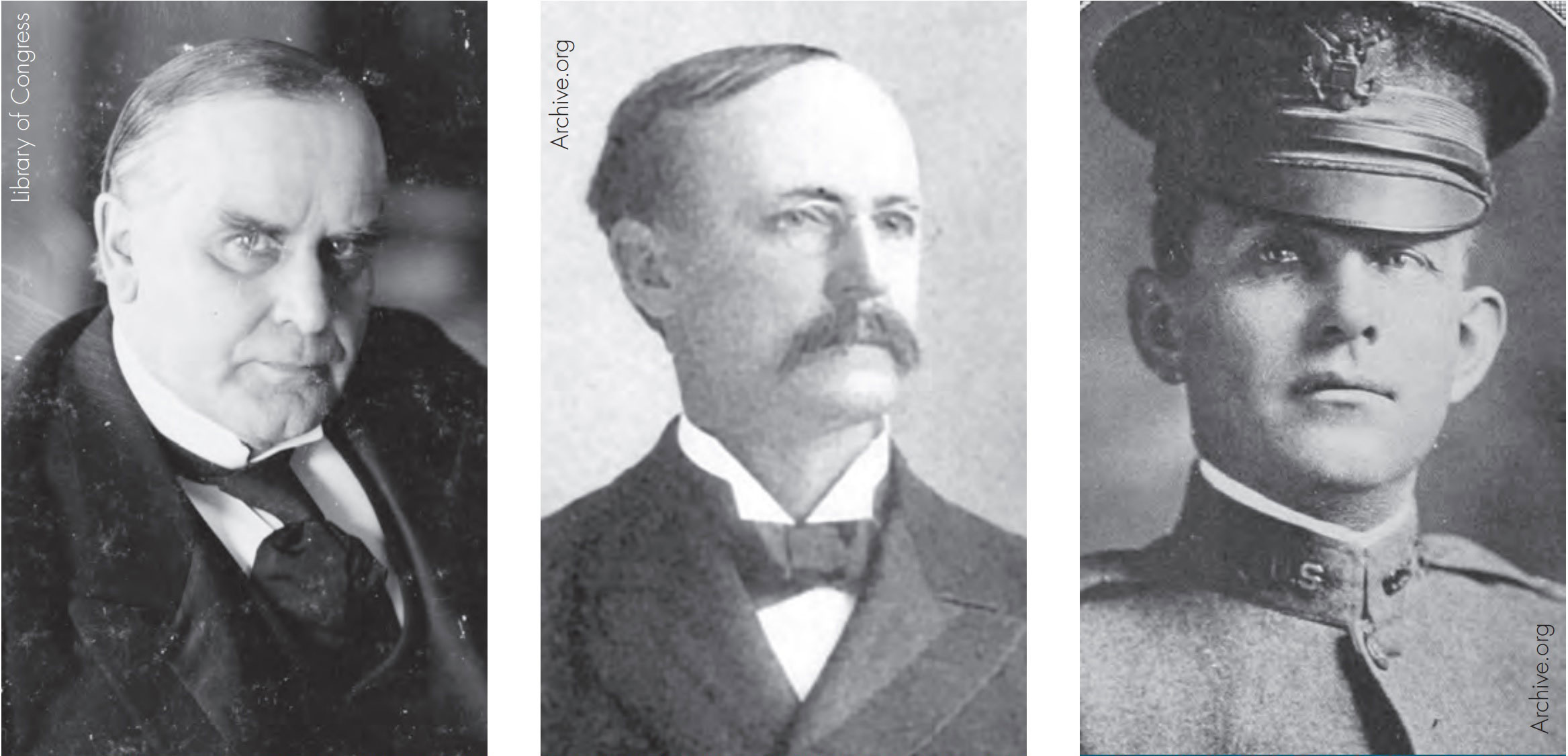

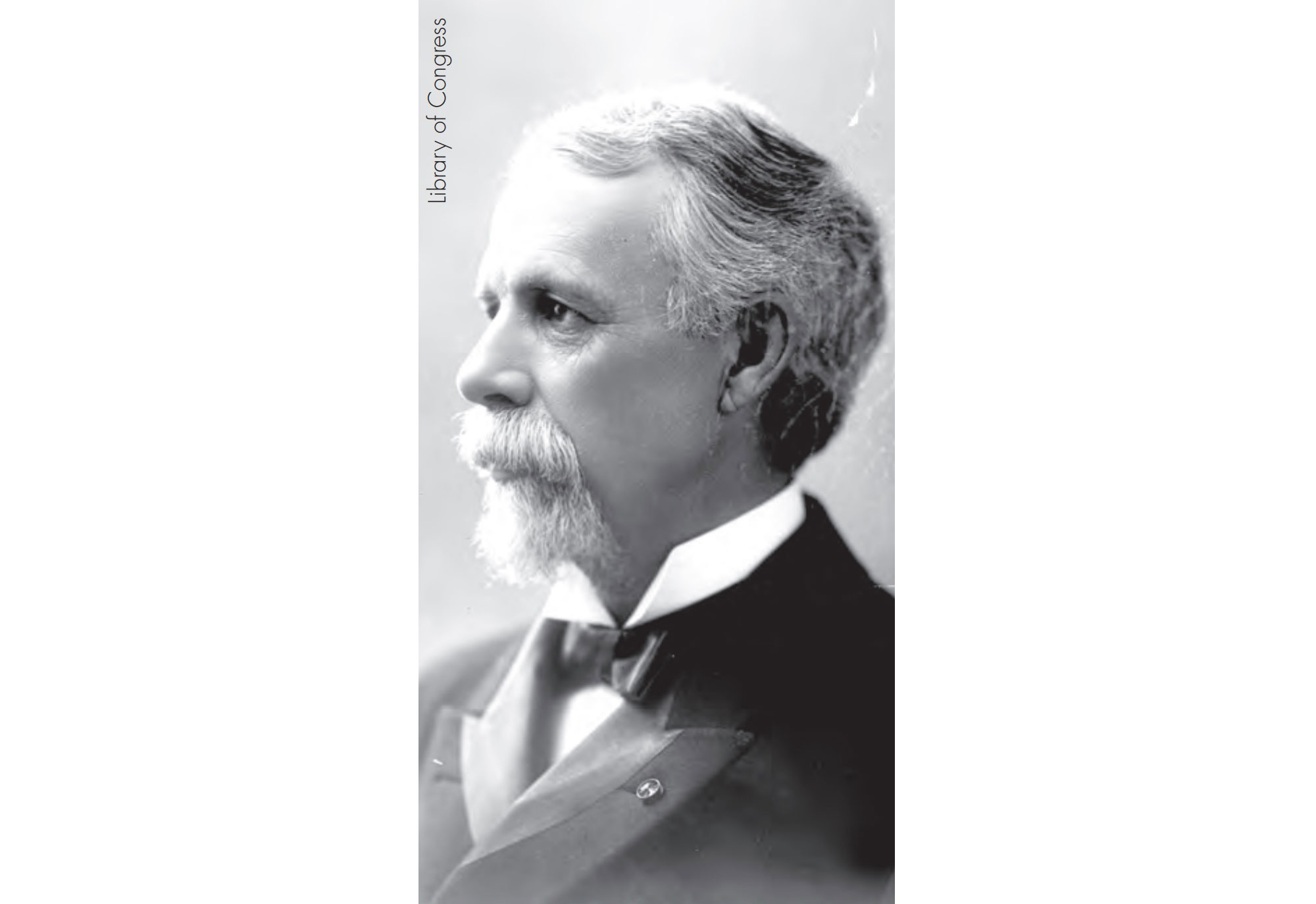

From left to right, President McKinley, c. 1989, Senator Thurston, c. 1899, Lieutenant Stewart, c. 1898.

On 12 January 1898, a large riot broke out on the streets of Havana that finally brought about American intervention. The instability of the situation concerned President William McKinley because of the threat to thousands of Americans living on the island and the millions of dollars invested in the Cuban economy. The riot compelled the president to send the armored cruiser USS Maine to Havana Harbor to project American power and protect American interests. The ship arrived in Havana on 25 January 1898. On 15 February, after three uneventful weeks, the Maine suddenly exploded, killing 260 sailors and marines.5 The investigation never linked Spanish action with the explosion, but the Maine incident quickly became the catalyst that sent the United States hurtling toward war with Spain.

President McKinley attempted to stem the public furor to go to war, but to no avail. After much consternation, he requested a $50 million appropriation, dubbed the “Fifty Million Bill,” for the purposes of national defense. The House of Representatives and the Senate unanimously passed the bill in early March, with $16 million earmarked for the Army and coastal defense.6 McKinley negotiated with Spain, which agreed to multiple demands for resolving the conf lict, with the exception of evacuating Cuba. Political pressure for war was fierce. U.S. Sen. John Thurston, a Republican from Nebraska, visited Cuba and reported 210,000 Cubans dying after Spain’s soldiers had driven them from their homes. Both houses of Congress encouraged intervention as Spanish forces and insurrectionists reached a stalemate: Spain could not stop the revolution and the Cubans could not drive Spanish rule from the island. The people of the United States pressed the government for action.7

The American preparations for war quickly escalated when, on 22 April, Congress gave the president the authority to call for volunteers to increase the size of the Regular Army from its current strength of 26,000. The following day, the president called for 125,000 volunteers. Congress declared war on 25 April and passed a bill the next day to double the size of existing Regular Army regiments.8 War planners decided that Tampa would serve as the embarkation point for the Cuban campaign, but the port lacked the infrastructure to execute the mission. Nevertheless, war had begun in bungling earnest. Second Lt. Merch Stewart described the mobilization as:

out of seeming chaos, brigades and divisions began to take form and substance. Gradually, also, regiments began to migrate Tampa-ward in preparation for we knew not what. Incidentally, we began to receive recruits whom we had no time to train, various articles of winter clothing, for which we had no use, and other impedimenta which were chiefly impedimenta.9

Time was of the essence, with men and equipment headed to Florida for the invasion of Cuba.

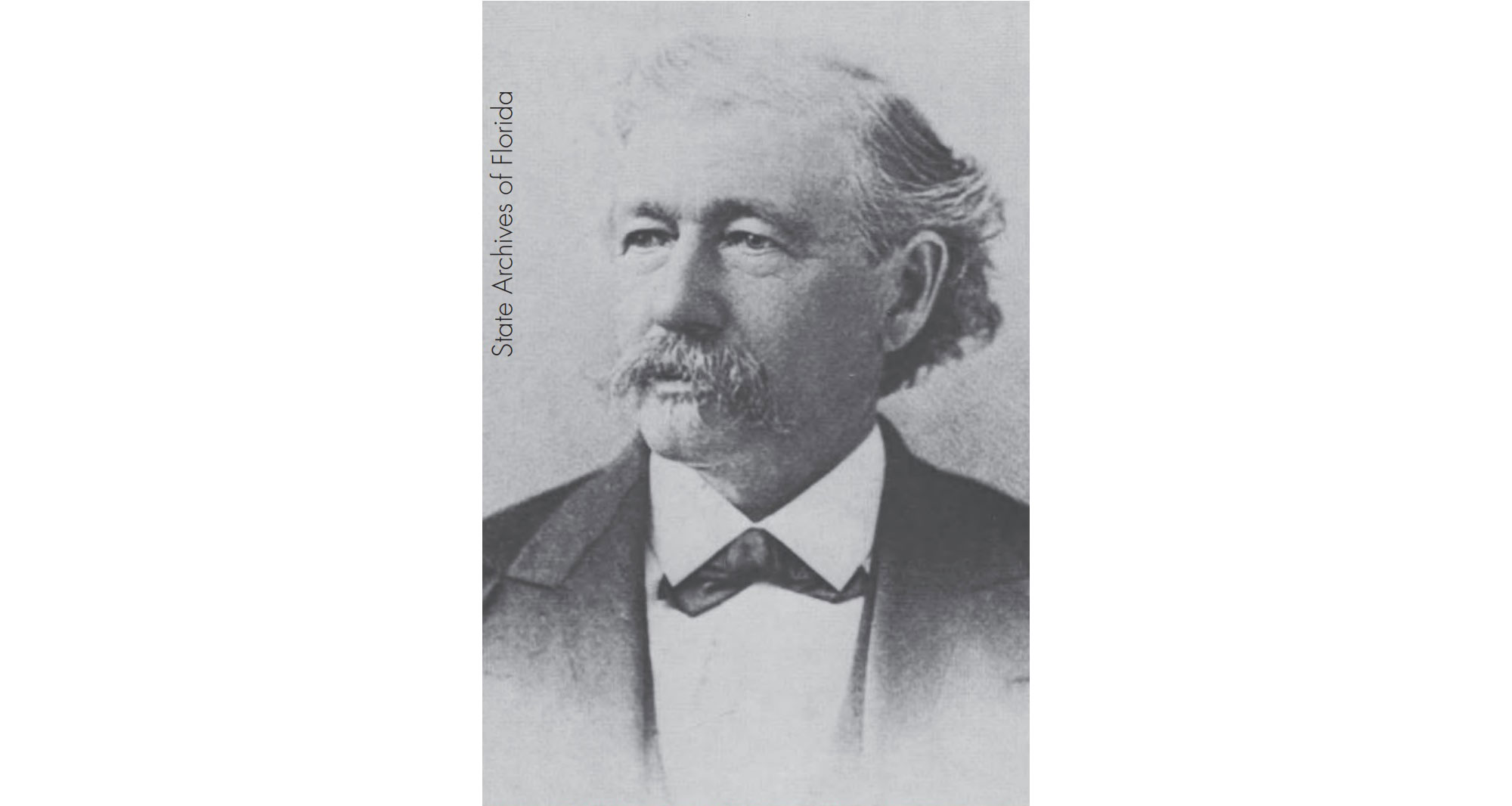

Tampa was a sleepy town on the Florida Gulf Coast with a population of 10,000 residents. Cigar making was the main industry. The town consisted of three banks, one movie theater, a transportation network consisting of gravel and planked roads, a handful of general stores, and one telegraph office. The main attraction was the Tampa Bay Hotel that rested on six acres with a silver dome covering a small casino. Henry B. Plant owned the property, along with the small one-track railroad leading nine miles from Tampa to the Port of Tampa.10 Plant had built the Port of Tampa to facilitate the flow of sea traffic from Key West and Cuba. In the port itself, a narrow channel allowed steamers access.11

Library of Congress State Archives of Florida Henry B. Plant

The channel’s twenty-one foot depth was adequate for large ships, and the wharf allowed thirteen vessels to dock simultaneously.12

The War Department had selected Tampa and the adjacent bay for their strategic advantages. Tampa Bay’s geography was ideal to prevent Spanish cruisers from engaging transport ships during the loading process because the port was far enough inland to discourage enemy ships from entering and risk being trapped.13 The location also possessed the minimum estimated railroad and shipping facilities for transportation support and was the closest port to Cuba with adequate naval capacity.14 With these considerations in mind, planners chose Tampa “almost by administrative gravitation,” and the Army began assembling on 15 April 1898.15 In retrospect, had the planners known the size to which the assembled force would grow, they likely would not have chosen the Port of Tampa as the embarkation point.16

The Tampa Bay Hotel, c. 1898

At the start of the mobilization, Secretary of War Russell Alger ordered 5,000 Regular Army troops to prepare for quick movement into Cuba.17 Upon arrival in Florida, units camped in the sandy terrain and waited for their imminent movement overseas. The staging process at Tampa captured the essence of the Army’s modernday deployment doctrine designed to combine troops, equipment, and supplies into one cohesive fighting force.18 In effect, Tampa was both a port of embarkation and debarkation. This was in contrast to New York City during World War I, where New York was a port of embarkation for thousands of soldiers brought there by railroads and planners executed only the movement phase of deployment operations. Three factors during the planning process dictated the reasoning behind Tampa as the site of deployment: establishing basing, maintaining tempo, and extending operational reach. Planners selected this site to receive units, integrate them with their equipment, and quickly facilitate movement into Cuba via ocean vessels.

Tempo was critical to the deployment through Tampa.19 The U.S. Navy had sent a force to blockade the Port of Havana with additional orders to destroy the Spanish fleet and set conditions for an Army landing force. Tampa had to be able to quickly receive, stage, and move soldiers to Cuba following any naval action. Therefore, maintaining a consistent pace in the Cuban campaign was essential to preserving the initiative gained by the destruction of the Spanish fleet. The Army needed to provide soldiers and supplies quickly in support of the Cuban insurrection. Additionally, the War Department believed that the rapid arrival of American ground forces would demoralize Spanish forces and boost the morale of Cuban rebels.

Operational reach is the ability of a military force to project combat power and sustain mission effectiveness through supply lines. It relies on basing to deploy forces and sets the initial tempo of the operation.20 Deployment sites form the foundation of projecting an army’s ability to fight any campaign. As military theorist Carl von Clausewitz wrote, the larger an army becomes, the more dependent it is on the base, thus the flow of men and materiel to the field of battle from the base becomes more restricted as the size of the army grows.21 Military planners assumed a large degree of risk when they anticipated that the Army could build enough infrastructure capacity at Tampa to mobilize and deploy armed forces to retain the initiative.

Secretary Alger, c. 1900

Beginning in early May 1898, mustered volunteers began pouring into Chickamauga Park, Georgia, for initial assembly, training, and follow on movement.22 From assembly points like this, enlistees typically moved to one of four sites: Camp Thomas, Tennessee; Tampa, Florida; Camp Alger, Virginia; and the Presidio of San Francisco, California.23 By the end of May, 163,626 soldiers had enlisted.24 While the government met the goal of increasing the fighting force, the Army’s organizational and institutional culture could only support a small, constabulary force. The Army’s entire logistics system consisted of a mere 22 commissary officers, 179 medical officers, and 57 quartermaster officers.25 This was simply not enough staff to support the increasing size of the Army. Still, there was no time to lose, and the desire to maintain the pace of deployment overruled logistics support. The original plan called for 5,000 soldiers to muster in Tampa. Sailing south, they would land in Cuba, conduct a reconnaissance-in-force, gain valuable intelligence, and aid the insurgents in whatever way they could.26 On 29 April 1898, an order from the adjutant general of the War Department directed Brig. Gen. William R. Shafter to “assume command of all the troops assembled there (Tampa).”27

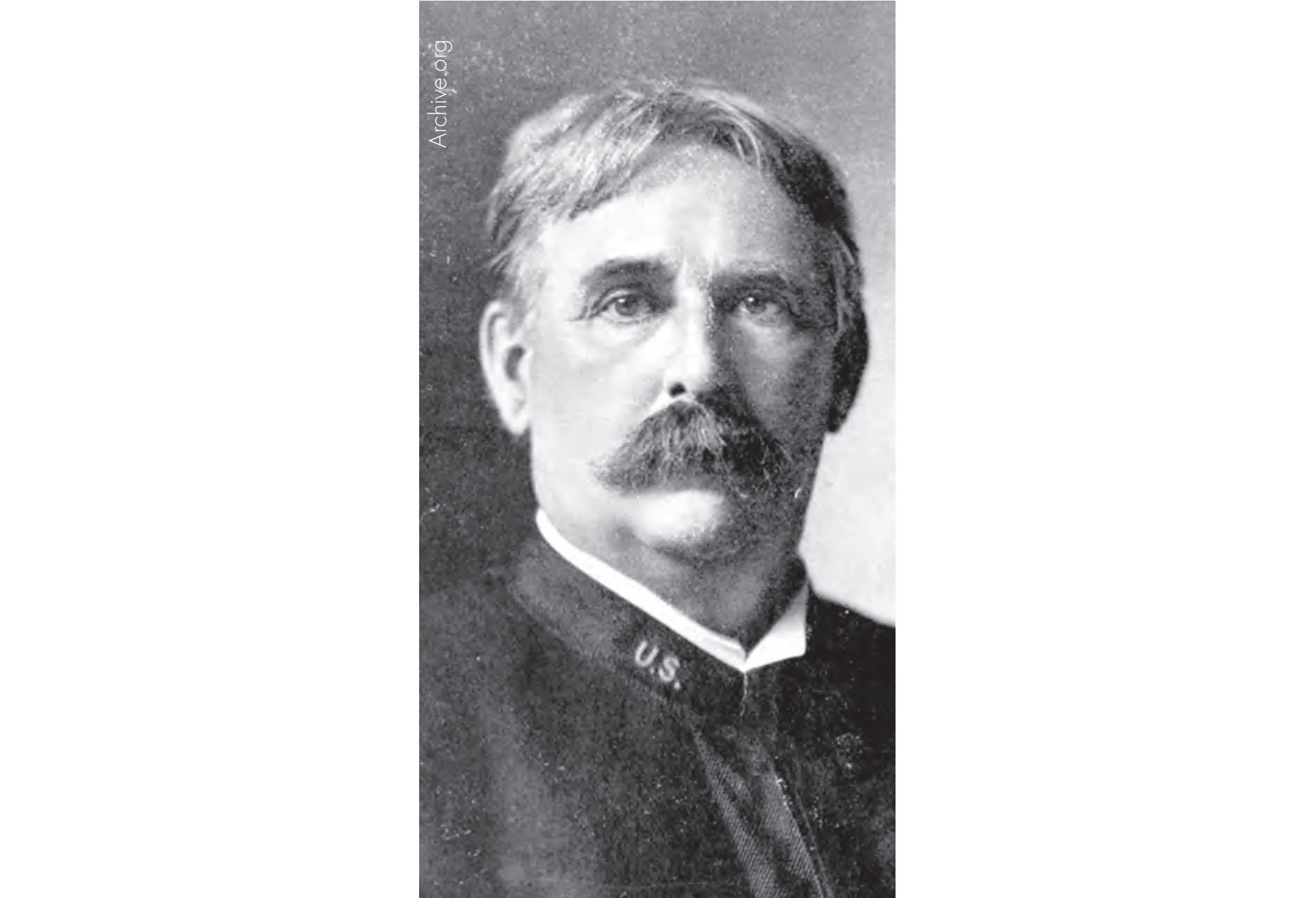

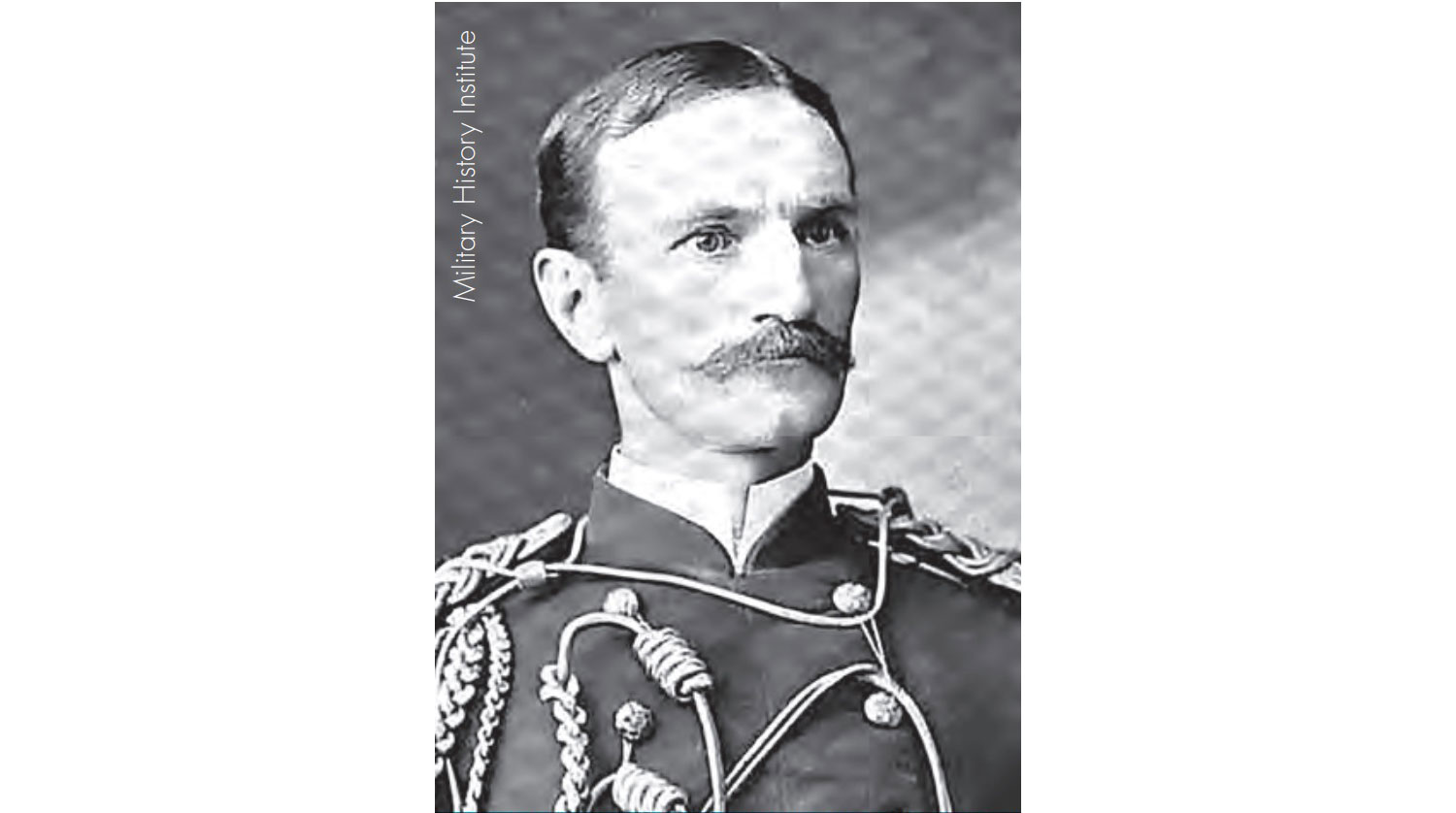

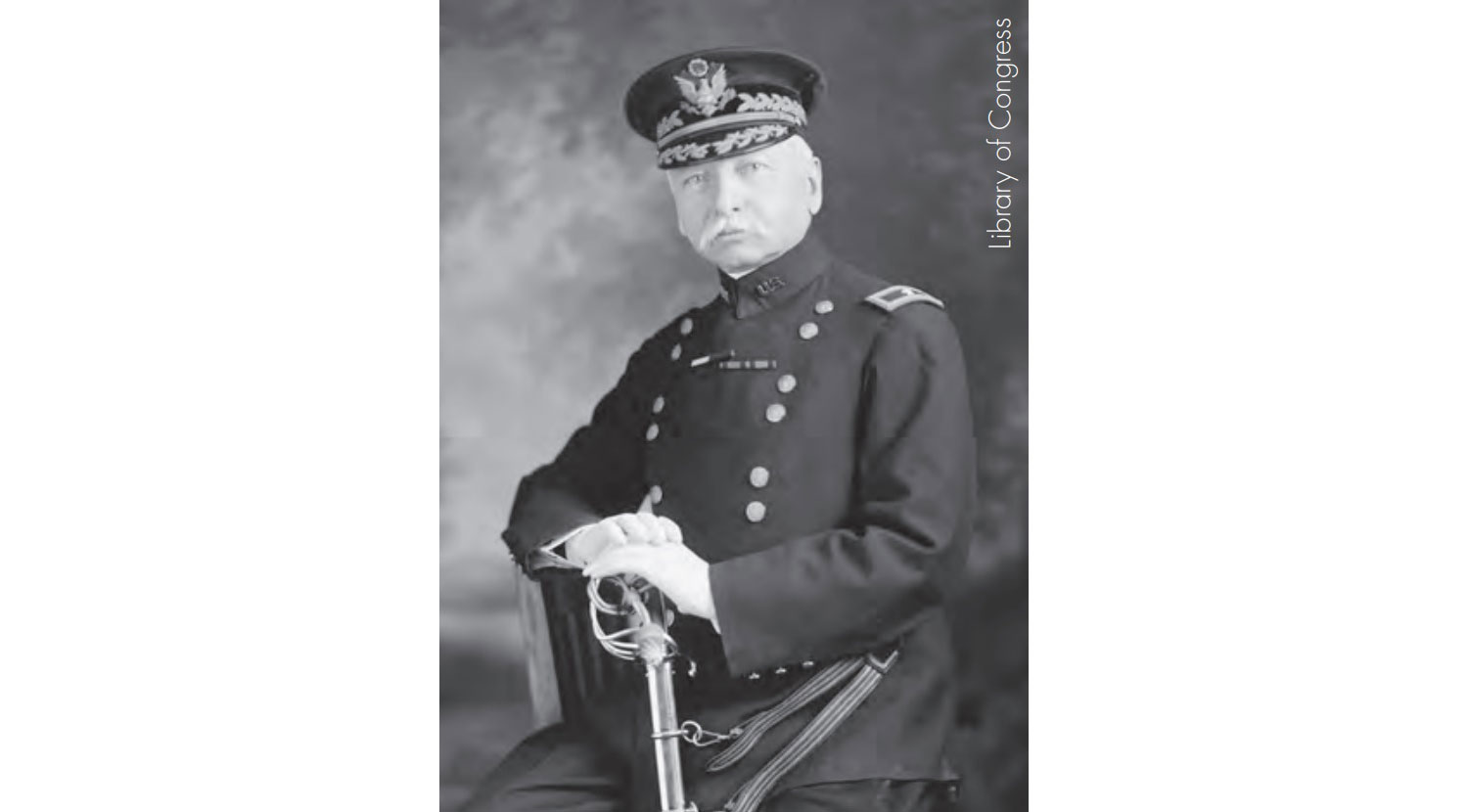

General Shafter

Shafter was born in rural Michigan and had enlisted in the Army before the Civil War. He earned the Medal of Honor for his conduct during the Battle of Fair Oaks, Virginia, on 31 May 1862, and continued his career across the plains in the Indian Wars throughout the 1870s. In 1897, Shafter received a promotion to brigadier general and assumed command of the Department of California. When the war with Spain began, Secretary of War Alger, Army Adjutant General Col. Henry Corbin, and Commanding General of the Army Maj. Gen. Nelson A. Miles unanimously chose Shafter as the expeditionary commander. Shafter was a large, stout man who weighed over 250 pounds following his years of sedentary garrison command. His chief commissary officer, Col. John F. Weston, stated Shafter “couldn’t walk two miles in an hour, [and was] just beastly obese.”28 Despite his weight, his peers described him as a brave soldier who contemplated decisions and did not make impulsive choices.29 Shafter’s one major shortcoming was his limited experience in the administration of large units. In Tampa, he failed to bring order to the port of embarkation, delegate command authority, or focus on the important details of unit departures.30 While senior leaders had chosen a seasoned commander to conduct combat operations in Cuba, they did not get an officer with the experience necessary to manage the vast sustainment challenges inherent with deploying the force from Tampa.

The Reception Process

The original call for the stationing of 5,000 troops at Tampa occurred one week before the official declaration of war on 25 April 1898.31 General Shafter arrived in Tampa on 30 April and received directions from the War Department. His orders were to maintain the pace of operations and sail at the earliest date possible with infantry, cavalry, artillery, and engineer forces. The American expeditionary force would land on the southern coast of Cuba to establish contact with General Maximo Gomez, the commander in chief of the insurgent army. The expedition would provide the rebels with supplies, arms, and ammunition. Shafter, though, was to avoid becoming decisively engaged, his main effort was to improve insurgent morale. However, Shafter soon received conflicting orders to delay any movement because there were Spanish warships spotted near Cuba. Preparations for deployment were to continue, and the expedition was to wait for further instructions.32

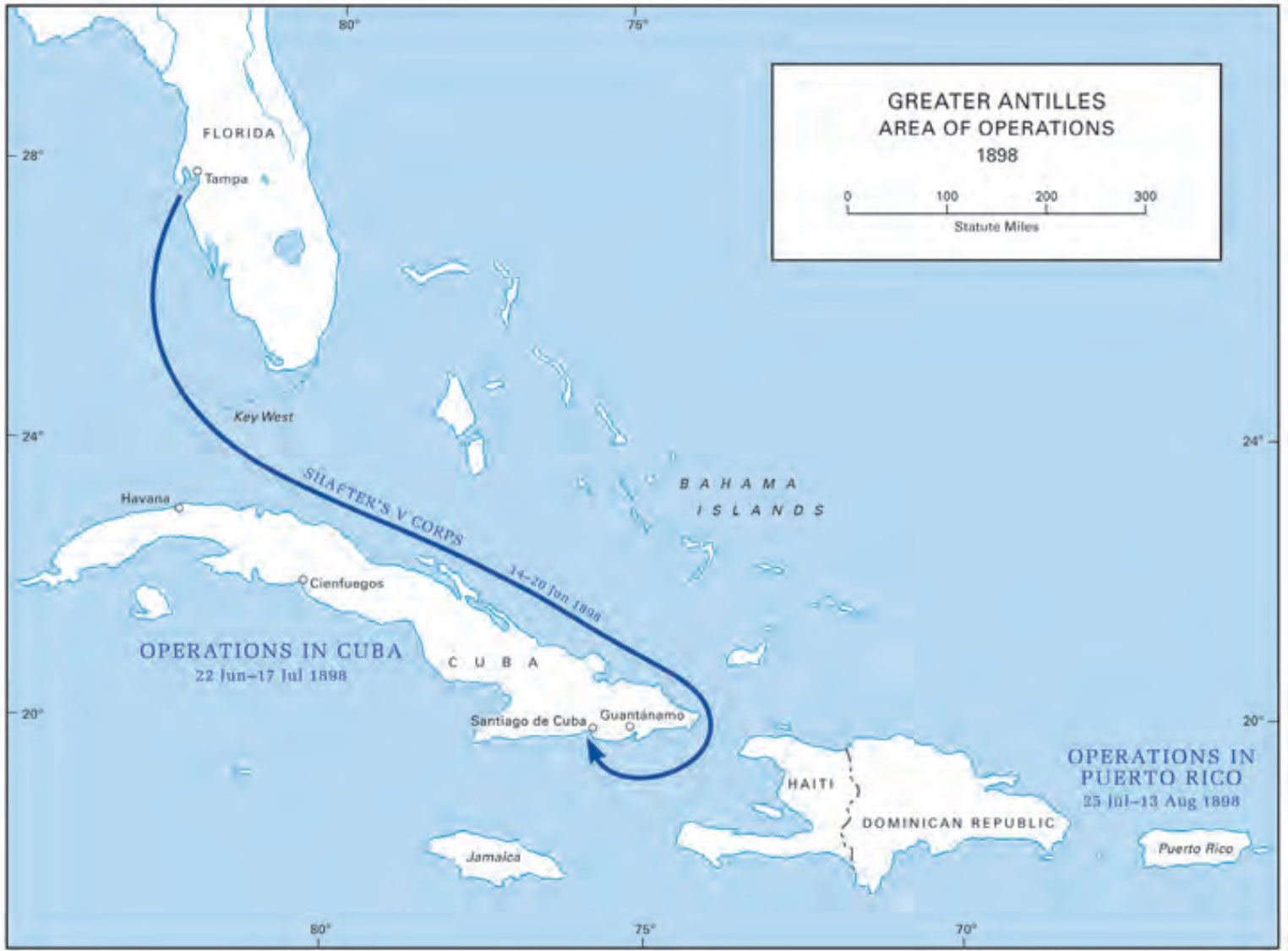

A map of the Greater Antilles Area of Operations 1898.

The plan for rapidly deploying the small contingent of 5,000 soldiers evolved into an unwieldy and lethargic force waiting for orders in the Florida heat. Moreover, in accordance with War Department directives, the number of troops began to increase—first to 12,000, and then to 25,000.33 The War Department did not anticipate the logistics needed to support this increase, and no one prepared Tampa for the challenges to come. On 10 May, Lt. Col. Charles F. Humphrey assumed command of the quartermaster department at Tampa. His command included ocean transportation and oversight of the depot quartermaster and chief quartermaster.34 Working with his assistant, Capt. James McKay, Humphrey focused his efforts on preparing the staging and movement process from Port Tampa to Cuba.35

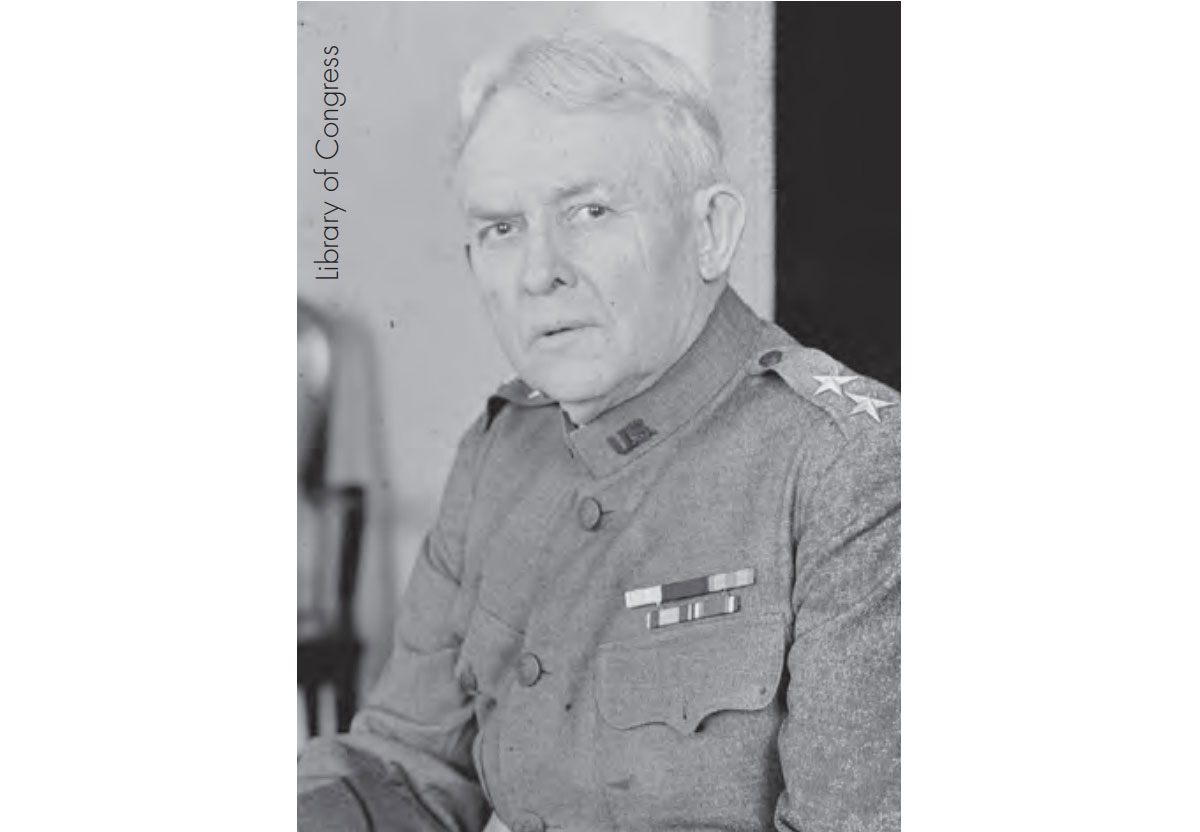

Charles F. Humphrey, shown here as a major general, c. 1907.

Shafter, promoted to major general of volunteers in early May, delegated the logistical management of the docks, but failed to establish a concept of reception for the thousands of troops about to arrive in Tampa. The modern-day reception process begins with receiving inbound units at transportation nodes and transitioning them to the next station. This process includes welcoming and providing guidance upon arrival, unloading equipment, marshalling troops into assigned areas, and providing sustenance and shelter for a temporary stay within the base.36 This orderly process coordinates incoming personnel and equipment while managing the flow of transitioning units. Tampa had no plan in place to manage this process effectively.

For 6 weeks the Regular army had been assembled at Tampa, enjoying a scene rather curiously combining aspects of a professional men’s reunion, a county fair, and, as the volunteer regiments began to arrive to augment the force, a major disaster.37

Planners had given very little thought to Tampa’s limited capabilities to transport and house men and materiel. The War Department continued to push troops and supplies into the area without assigning a commander to organize this complicated logistics effort. Additionally, Shafter did not assign a leader to coordinate the process from reception to embarkation.38 The result was general confusion for arriving troops. As one reporter wrote,

The United States troops who arrive in Tampa . . . are dumped out on a railway siding like so many emigrants. No staff officer prepares anything in advance for them. Regiments go off in any direction that suits them, looking for the nearest place where they may cook their pork and beans.39

Pvt. Charles Post of the 71st New York Volunteer Infantry arrived by train at nearby Ybor City, where he proceeded to walk three miles to the Tampa camp in the Florida heat. After his regiment suffered numerous heat stroke casualties on its march, the men settled in a wide-open area and dug latrines near the camp.40 The intended plan was for units to arrive and report to the headquarters in the Tampa Bay Hotel and receive their billeting locations.41 However, General Shafter and his command gave few instructions to units upon arrival.

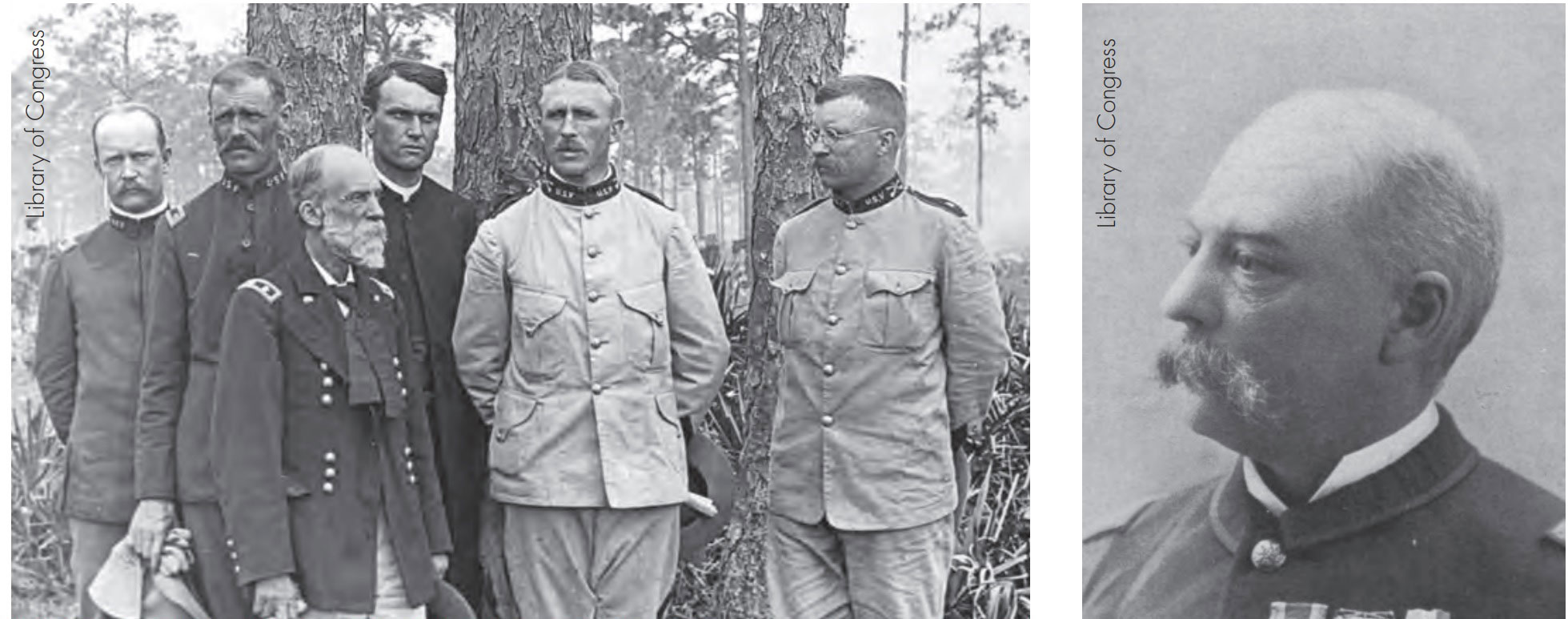

Image left: Staff of the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry in Tampa, c. 1898. From left: Taylor MacDonald, Maj. Alexander Oswald Brodie, General Wheeler, unidentified officer, Colonel Wood, and Colonel Roosevelt. Image right: General Wade.

When Lt. Col. Theodore Roosevelt, with the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry, reached Tampa, he described the conditions as “a perfect welter of confusion.” When the train arrived and disembarked the soldiers, there was no central authority to receive his “Rough Riders,” no guidance on where to camp, and no food for the first twenty-four hours. The future president stated that,

“everything connected with both military and railroad matters was in an almost inextricable tangle.”42 Roosevelt’s commander, Col. Leonard Wood, was in total agreement when he stated, Confusion, confusion, confusion. War! Why it is an advertisement to foreigners of our absolutely unprepared condition. We are dumped into a grove of short stumpy ground in the dark and our animals on an adjoining place filled with 2100 loose animals.43

Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler arrived in Tampa on 13 May to assume command of the cavalry division in V Corps. After reporting to Maj. Gen. James Wade, Wheeler received no instructions for three days while waiting for orders from the command.44

The War Department failed to plan for supply requirements as troops arrived in Tampa. Many of the units required four days of travel from their mobilization camps, but the supply system provided only two days of rations. The lucky ones received food from local residents and churches on arrival in the region.45 The incoming troops found limited camping grounds and an insufficient water supply.46 Three to five regiments arrived in Tampa every day. By 25 May, the expanding soldier population of now 17,000 troops began to overcrowd the Florida port. Due to increased congestion and lack of facilities, Shafter made the decision to open up additional camps in Lakeland and Jacksonville to alleviate the burden on the Tampa infrastructure.47 The reception process was a failure due to the lack of unity of command and because no one was in charge to synchronize unit arrivals with land allocation, supplies, or leadership. There was never any plan to support this influx of personnel, and there was no published timeline of unit arrivals. However, as bad as the troop reception was, the receiving of equipment was worse.

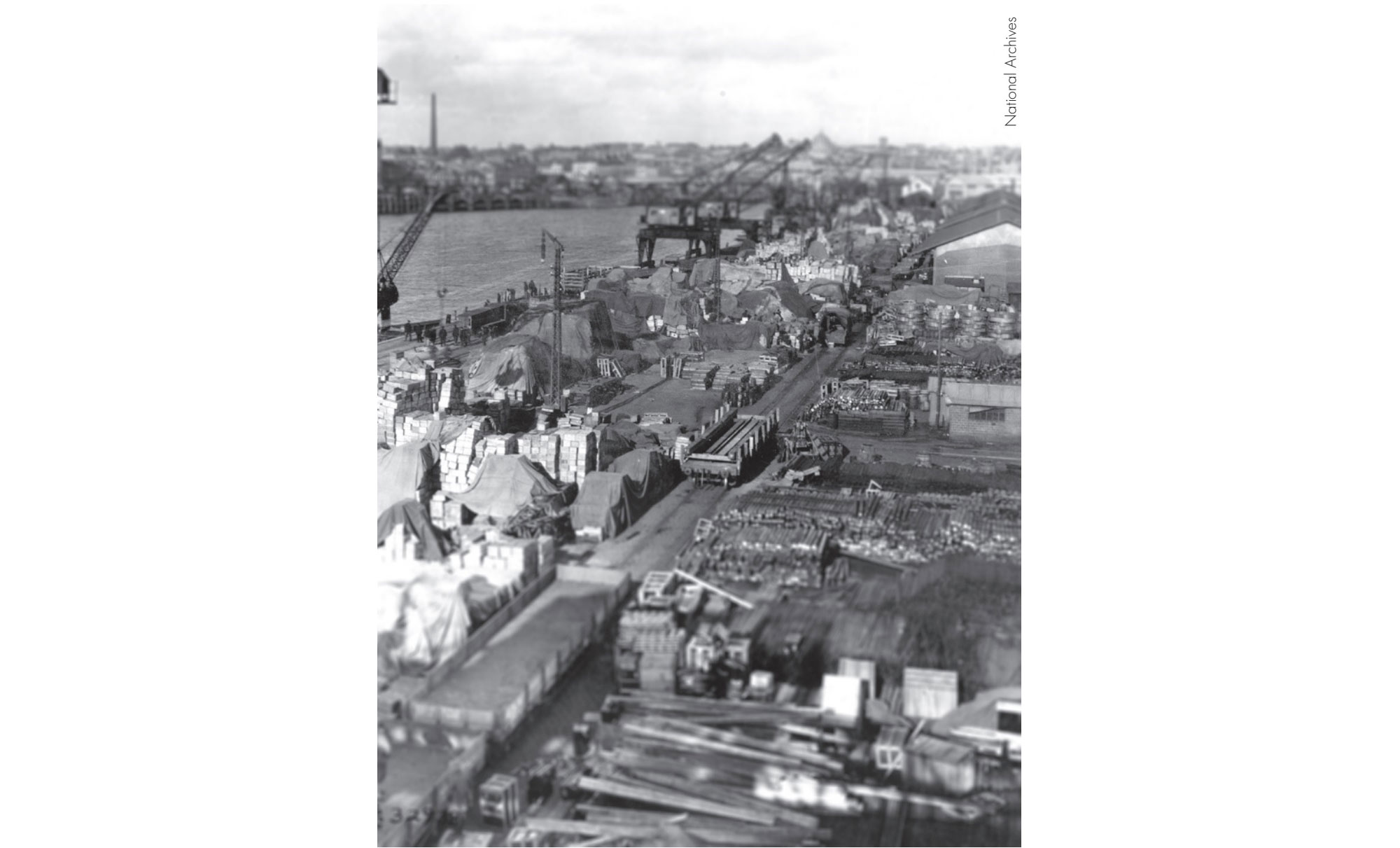

View of a dock at the port of Tampa with moored ships and boxcars being unloaded, c. 1898

In accordance with the time-honored Army tradition of “hurry up and wait,” the incoming soldiers’ rush to Tampa was followed by weeks of waiting. Meanwhile, quartermaster and commissary officers worked on the chaotic tasks of organizing the thousands of tons of arriving supplies.48 The two main issues faced were the lack of railroad infrastructure and the privatized commercial transportation options, which were monopolized by Henry Plant. There were only two railroad lines leading to the City of Tampa. From there, one line proceeded nine miles to the Port of Tampa. Plant independently operated this line and refused to allow other rail companies to use it.49 Complicating matters, Plant ran sightseeing trains on his line to allow citizens the opportunity to observe the military activities. He also allowed train and boat services to continue in the harbor.50 The backlog these two factors created was tremendous as equipment relentlessly poured into the small town.

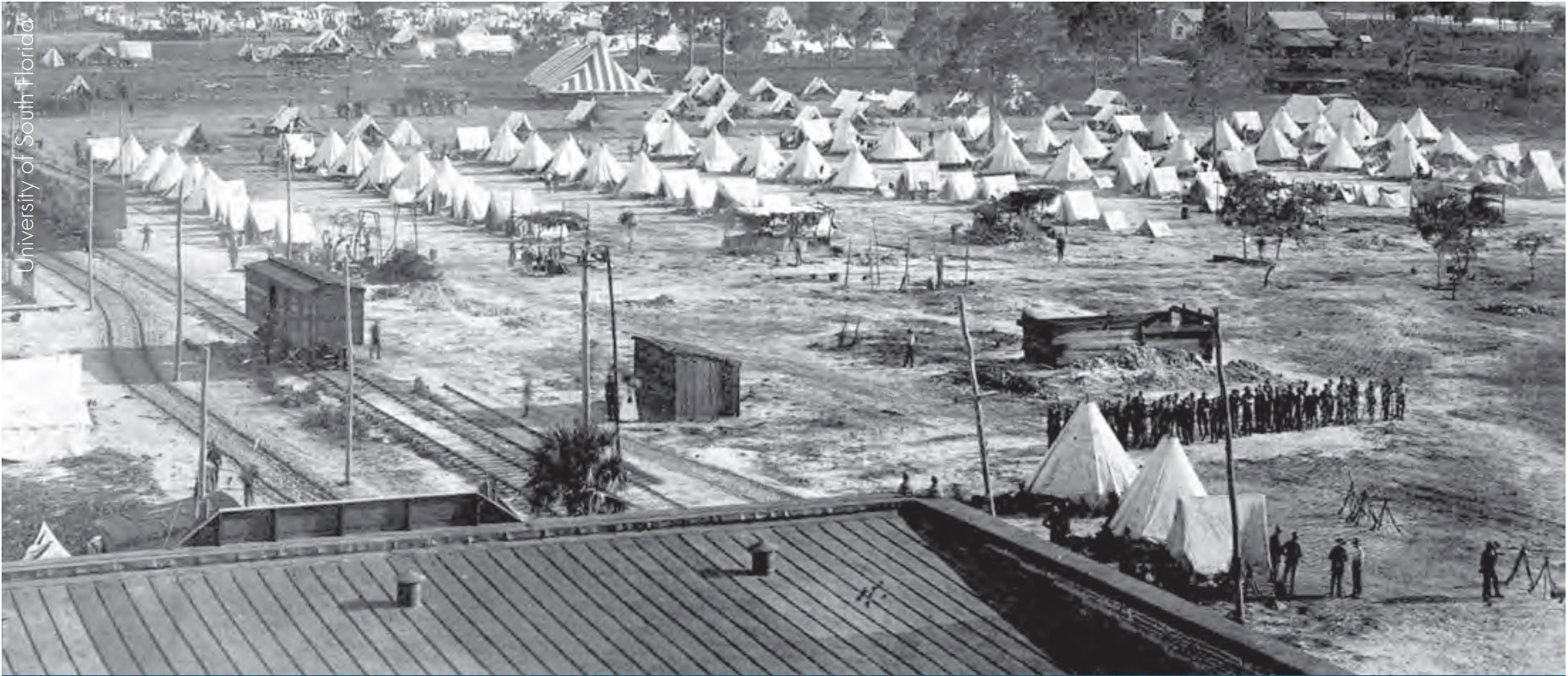

Aerial view of military encampment near Tampa, c. 1898

By 18 May, there were more than 1,000 freight cars ready to be unloaded with a processing rate of only three per day. Trains were waiting as far north as Columbia, South Carolina, due to the backlogs. Train cars that did make it to Tampa remained loaded because of the lack of warehousing By 18 May, there were more than 1,000 freight cars ready to be unloaded with a processing rate of only three per day. Trains were waiting as far north as Columbia, South Carolina, due to the backlogs. Train cars that did make it to Tampa remained loaded because of the lack of warehousing University of South Florida University of South Florida Aerial view of military encampment near Tampa, c. 1898 View of a dock at the port of Tampa with moored ships and boxcars being unloaded, c. 1898 This content downloaded from 132.159.80.40 on Wed, 20 Dec 2023 14:03:01 +00:00 All use subject to https: 42 Army History Summer 2017 and on site transportation.51 Only five government wagons and twelve hired civilian wagons were on hand to facilitate loading and unloading.52 and on site transportation.51 Only five government wagons and twelve hired civilian wagons were on hand to facilitate loading and unloading.52

Incoming railroad companies feuded with both the government and Plant. The local developer refused to let competitors use his rail line and ordered his employees to transfer freight solely with Plant equipment. This only stopped when the Army threatened to take over the Plant line.53 The War Department shipped supplies with such haste that it neglected to label the railroad cars and in some instances, the bills of lading were weeks behind and each container had to be hand inspected.

Soldiers of the 71st New York Volunteer Infantry wait with their gear at the port of Tampa.

Units attempting to find the equipment they had shipped often took whatever supplies they came across first, leading to further confusion.54 With very limited warehousing, the troops unloaded the cars slowly to preserve precious storage space, but failed to organize the cargo with any semblance of logic.55 The reception process was a total failure and backlogs mounted. The loading parties could not keep up with the inf lux of equipment, delaying the expedition’s readiness to sail. In contrast, Shafter required his expeditionary force staged and ready to react to a short-notice order to deploy to Cuba.

Staging Process

The staging process organizes personnel and supplies into combat formations, ready to deploy as a cohesive fighting force. It joins soldiers to their equipment, and places them in arranged locations to deploy, in accordance with a planned timeline and provides logistics support for units flowing through.56 The conditions established at Tampa failed to lay the groundwork for successful staging operations.

The water supply was short; machinery broke down; siege guns had to be carried bodily for miles; supply trains were stalled; mules and horses that should have arrived had been left behind in some unknown locality; troops coming in from a dozen different camps in a dozen different stages of unpreparedness—such were the few of the tangles, drawbacks and difficulties that had to be met, unraveled, and conquered before the great transport fleet could get on her way.57

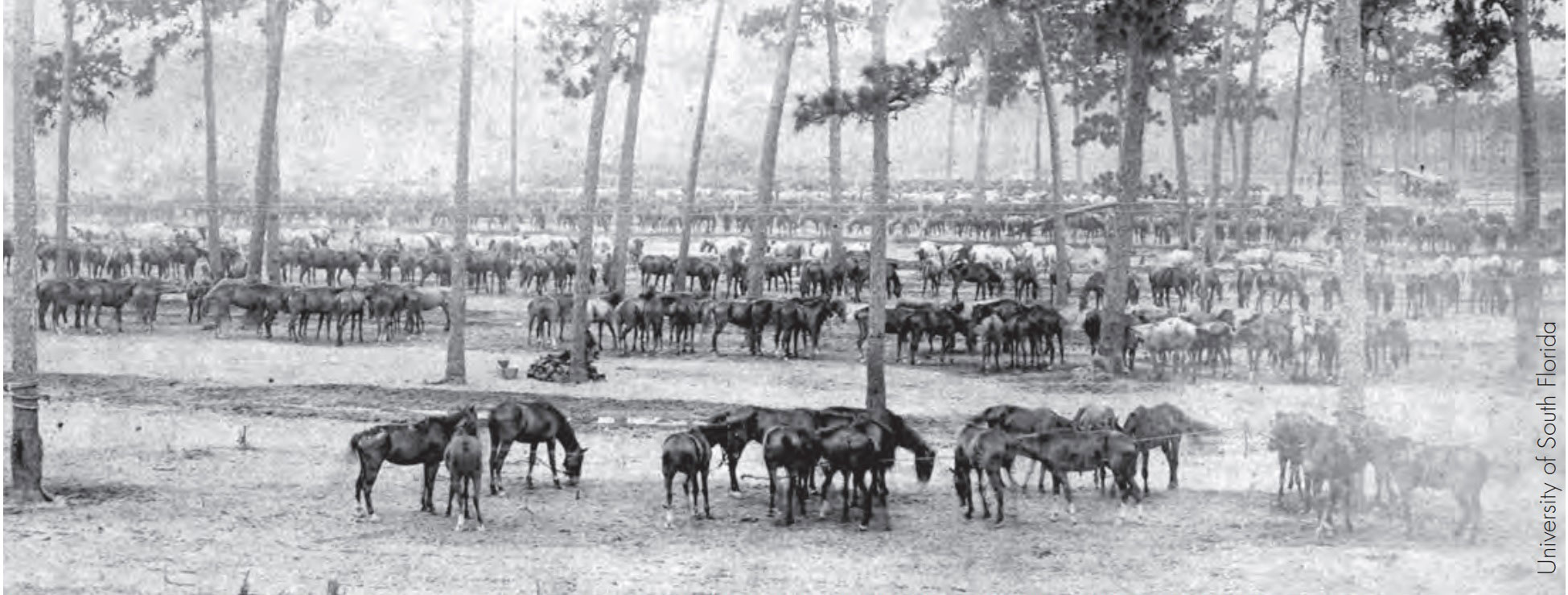

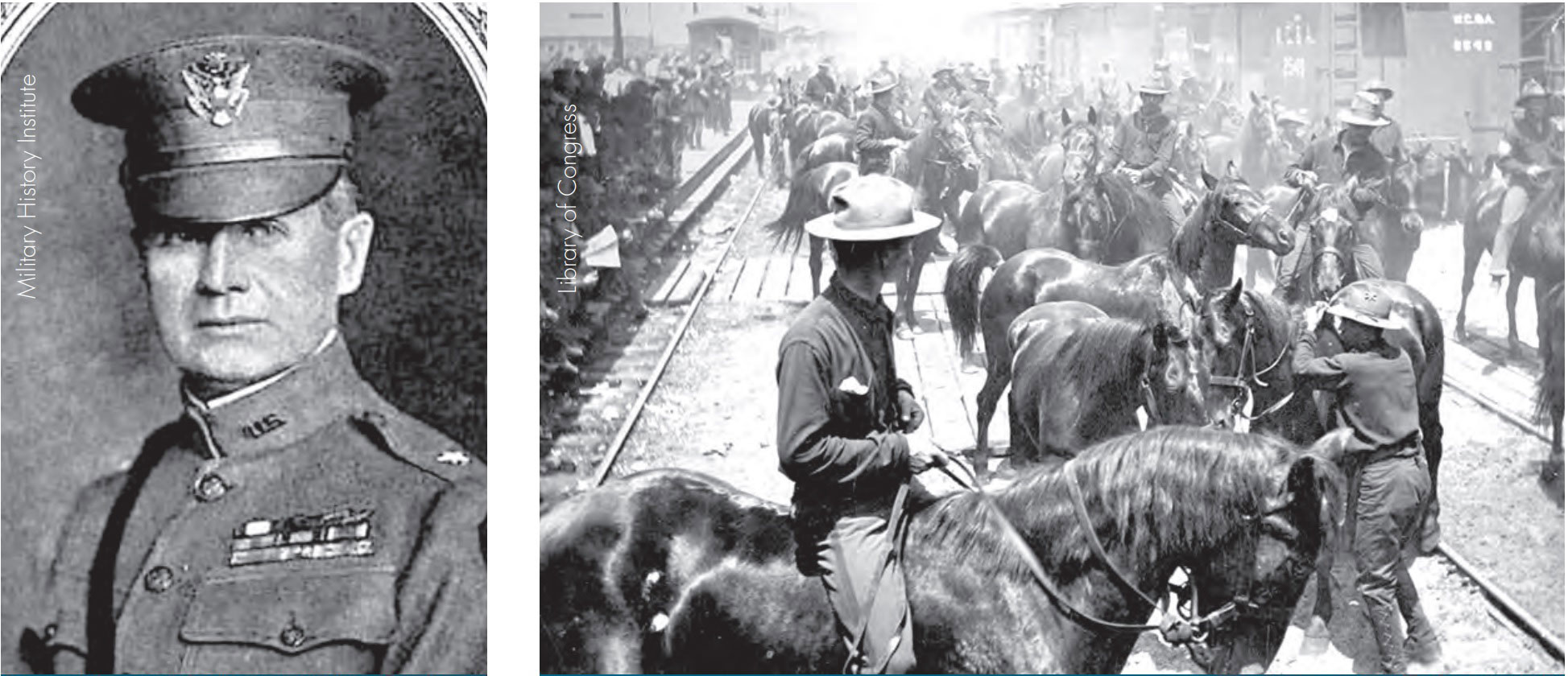

Horses corralled near Tampa waiting for shipment to Cuba

Yet, in anticipation of the Navy destroying the Spanish fleet, the War Department expected the expeditionary force to load transports at a moment’s notice and move quickly to Cuba. The expedition simply was not ready to embark due to the lack of preparations.

Providing logistical support to incoming units was problematic. The lack of water and sanitary facilities forced units to encamp in small towns several miles from Tampa. The small post office could not identify packages destined for staged soldiers due to the lack of mailing labels. Units received supply and organizational equipment in an untimely manner or not at all, and materiel shortages contributed to insufficient and incomplete training.58 Animals, including cavalry horses and mules to haul wagons, required more fodder than was available.59 Ammunition was not in adequate supply and the War Department could not accurately predict when sufficient quantities would arrive.60

The artillery force faced a unique problem with its field pieces, a condition that lasted through arrival in Santiago. Manufacturers shipped artillery components piecemeal in separate freight cars from different factories. Artillery batteries had to seek out separate shipments of caissons, carriages, field pieces, and ammunition to assemble and ready their guns.61 Many components remained on unidentified boxcars twenty-five miles outside of Tampa through the end of May.62 The original plans had called for transitioning the artillery batteries to a war footing and creating larger six-gun batteries, but the supply issues were overwhelming.63

The preparation of the transports was the final staging action necessary. When the United States declared war, the Army owned no shipping vessels. It managed to obtain four by the end of April and thirty by the end of May; however, none possessed the proper ventilation systems or facilities necessary for transporting large numbers of men. The government purchased these ships from privatized freightliners in the Gulf of Mexico.64

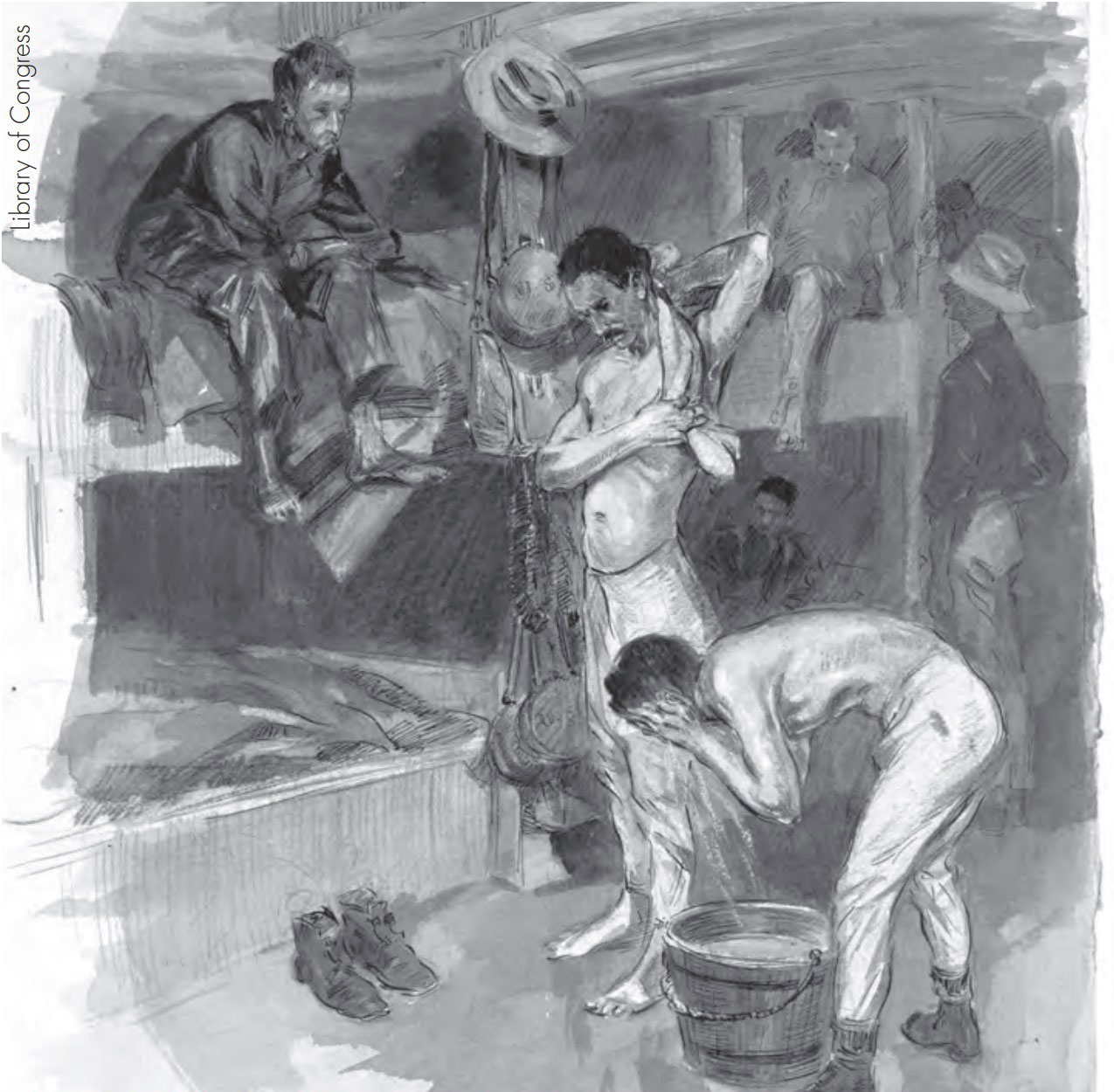

Sketch by William Glackens showing soldiers in their berths and bathing aboard a transport bound for Cuba, c.1898

The War Department invested a huge amount of manpower and resources to turn these freighters into troopships with bunks, water storage tanks, and proper ventilation.65 In total, the War Department purchased thirty-nine vessels at a cost of $7 million, a sum not included in the allocated “Fifty Million Bill.” When completed, the transports could sail for thirty straight hours but only provided minimal comfort for the troops.66 The men would have to take turns sleeping on bunks, and, in the worst case for one vessel, engineers only had enough room to install twelve toilets for a compliment of 1,200 soldiers.67

Workers converted the Miami and San Marcos from a cattle boat and a freighter, respectively, into transport ships. However, as one soldier from the 6th Infantry Regiment stated, “It was a misnomer to call these ships transports.”68 The quartermaster general originally estimated the new transport fleet’s overall carrying capacity at 25,000 soldiers, but this was quickly lowered to 17,000 due to space limitations.69

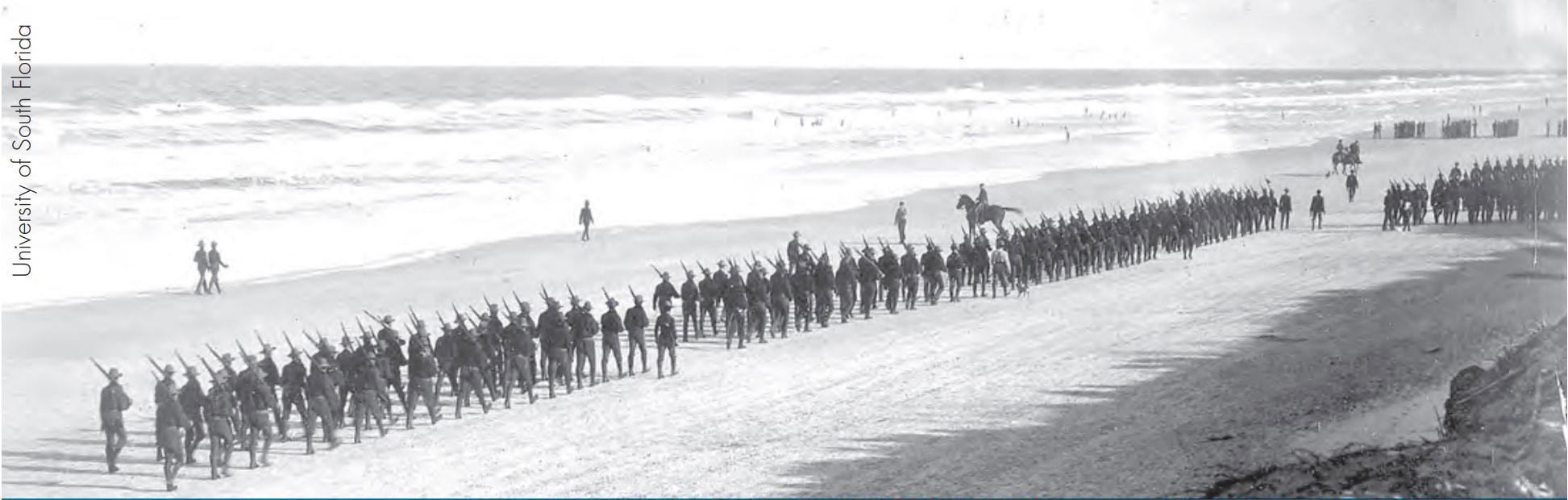

Most soldiers spent much of May in the hot Florida sun focused on preparing for war and entertaining themselves. General Miles issued orders on 30 May for officers to “labor diligently and zealously to perfect himself and his subordinates in military drill, instruction, [and] discipline.”70 Soldiers considered drill commonplace during staging, but the commanders wanted additional training. New volunteers with little to no combat experience arrived daily along with officers and noncommissioned officers largely unfamiliar with conducting training. In the 28 May edition of Harpers Weekly, correspondent Poultney Bigelow pointed out that units were training, but “the senior commanders had never seen their commands.”71 The oppressive heat shortened many drills due to soldier exhaustion, with the lack of water compounding the misery. Units completed drills early in the mornings and late evenings in order to avoid the heat. In addition, the limited space to maneuver supported only small-scale training exercises.72 Shafter considered this a liability and even contemplated moving a portion of the command northeast to Jacksonville, but the force never relocated and drills continued in the limited training space.73

Like the quartermasters, the commissary supply system was also inadequate at Tampa. The embarkation point experienced problems such as receiving rotten meat from the food contractors. Even when arriving on refrigerated train cars, soldiers opened food shipments that were often spoiled. The Department of Agriculture investigated and could find no evidence of tampering or wrongdoing.74 Nevertheless, unloading parties wore handkerchiefs around their faces as they transferred the putrid meat into ditches for quick burial. The troops dubbed the shipments “Alger’s Embalmed Beef” to assign blame to the secretary of war and his perceived lack of support for the Tampa expedition.75 The soldiers received their main supply of food from rations, which arrived via the Subsistence Department’s short notice purchases. Depot commissaries purchased and shipped sixty days of supply to Tampa, and Regular Army units en route to the embarkation point received thirty days of rations. This system, once it caught up to the number of soldiers in Florida, eventually stockpiled a ninetyday supply at Tampa for 70,000 men.76

Troops of the 3d Nebraska Volunteer Infantry march along Pablo Beach near Jacksonville, Florida, c. 1898.

The spoiled meat issue added to the overall concerns of the poor health of the camp. While there were no deaths in Tampa, there was a constant threat of dysentery and one outbreak of typhoid fever. The overcrowding, lack of supplies, animal waste, kitchen refuse, and rotten meat contributed to unsanitary conditions. However, the short stay in Tampa, compared to other camps, prevented unnecessary deaths from disease. The chief surgeon of the 5th Cavalry Division reported to General Wheeler the satisfactory Tampa camp conditions and health of the troops, with each unit possessing three to four weeks of medical supplies.77 Meanwhile, hundreds of soldiers died at various camps across the United States, including 425 who perished at Camp Thomas, Tennessee.78

Most of the volunteer units arrived without proper equipment. Planners designed supply stations at Tampa to equip newly enlisted soldiers with the needed gear during staging. However, lack of warehousing facilities coupled with shipping backlogs prevented an adequate on-hand supply. The availability of equipment determined distribution. At the quartermaster warehouse, a supply sergeant would guess the sizes of each soldier for uniforms, shoes, and hats. If incorrect, the exchange process could take as many as three days.79 The 28 May edition of Harpers Weekly mused that Congress declared war thirty days ago but,

not one regiment is yet equipped with uniforms suitable for hot weather. The Cuban Patriots and cigar-makers look happy in their big Panama hats and loose linen trousers, but the U.S. troops sit day and night in their cowhide boots, thick flannel shirts, and winter trousers.80

Most soldiers received only one set of clothing to replace their cold weather uniforms. The weapons situation was even more abysmal, with the depot commander refusing weapons requisitions for the units until they arrived at camp.81 This delay further exacerbated the supply problem.

The problems of inadequate supply and poor training led to an inordinate amount of idle time for the troops. Naturally, soldiers found plenty to do in Tampa to keep busy. Unfortunately, this also meant violating the second part of Miles’ orders to “maintain the highest character, to foster and stimulate that truly soldierly spirit and patriotic devotion to duty which must characterize an effective army.”82 Officers issued passes for the men to explore the local area, and the enlisted soldiers took advantage of this privilege. Some chose to walk peacefully around the Tampa Bay Hotel or visit the nearby towns. Others found ways to get into trouble, like Pvt. Frank Brito, who discovered an opium den in Ybor City.83 Unscrupulous entrepreneurs took advantage of the young population, as “there were plenty of locations for alcohol, good times, gambling, and prostitution.”84 A private with less than one month’s service received $10.35 in pay and could find plenty of ways to enjoy his paycheck. One night, Pvt. Charles Post assisted in retrieving unruly troops from Tampa; he observed hundreds of detained soldiers from his 1st Infantry Regiment.85

The waiting in Tampa continued through the last week of May. While the enlisted men occupied their time in the towns, the officers lounged in the Tampa Bay Hotel, reuniting and sharing war stories with old colleagues.86

Colonel Roosevelt noted general officers milling about the hotel with their staffs, women in pretty dresses, newspaper correspondents, and foreign onlookers from Great Britain, Germany, Russia, France, and Japan.87 Other notables seen around the hotel were Clara Barton, founder of the Red Cross; evangelist Ira Sankey; the adviser to the Cuban rebels, Capt. Andrew Rowan; Kaiser Wilhelm II’s observer, Count Gustav Adolf von Goetzen; and Roosevelt’s wife, Edith Carow Roosevelt.88 Maj. Gen. Shafter set up his headquarters in the hotel and continued to wait for word of the Spanish fleet’s destruction as the days ticked by.

Onward Movement Process

Onward movement is the forward progress of units transitioning from staging areas to follow-on destinations and applies to personnel and equipment.89 In Tampa, the changing nature of the strategic situation prevented Shafter from understanding how best to achieve the original goals of the McKinley administration, much less onward movement. While Shafter continued through all of May to prepare for a quick mission to provide moral and physical support to insurgents, the guidance from the president suddenly changed.

Colonel Miley

Lt. Col. John Miley, the aide-de-camp to Shafter, stated that on 26 May, the general received an order via telegram to prepare 25,000 soldiers for departure from Tampa. The War Department had issued the warning of a changing mission: the expeditionary force would now directly engage Spanish soldiers, but Shafter had no definitive details with which to plan.90 The following day, correspondence from Secretary of the Navy John Long shed some light on matters by emphasizing the Navy Department’s urgent pleas to mobilize soldiers to invade Cuba.91 Finally, on 30 May, General Miles issued orders to Shafter clarifying the exact mission of the expedition:

Go with your force to capture garrison at Santiago and assist in capturing the harbor and fleet. . . . Have your command embark as rapidly as possible and telegraph when your expedition will be ready to sail.92

This order expedited Shafter’s tempo of operations in loading supplies on the transports.

U.S. troops arrive aboard railcars in Tampa, c. 1898.

The force made all efforts to load the ships from 30 May through 6 June. Working well into the night, troops traveled forward from outlying camps. Supplies from warehouses in Tampa started movement toward the port, further congesting the single-track line. On 31 May, deck hands filled coal and water on the ships, and men began loading rations. The new orders called for 25,000 men to be supported for six months. This directive was subsequently lowered to two months along with an additional 100,000 rations scattered throughout the ships in the event of separation. The work of loading artillery wagons, guns, and caissons began on 1 June. Artillerymen now sensed the urgency of finding disparate components and linking them to form complete gun systems. The men spent considerable time consolidating commissary rations that shipped in separate railcars.93 The single-track line created and exacerbated delays in moving materiel to the port.

Supplies being loaded aboard ships at the port of Tampa, c. 1898.

Simultaneous activities at the harbor caused a bottleneck. Once equipment finally arrived at the dock, contracted stevedores became the driving force to load the ships. This was no easy task, as the goal was to maintain unit integrity with equipment as they assigned units to vessels. With limited berths, the ships continuously rotated within the narrow port to align with arriving railroad shipments, which caused further delays.94 The stevedores mostly loaded equipment from the railcars by hand across fifty feet of sandy terrain and then up steep ramps to the vessels. Once their shifts were over, many of these men fell asleep on the spot where they last stopped working due to exhaustion.95 All these difficulties notwithstanding, the contractors loaded over 10,000,000 pounds of materiel. The ration trains moved from one ship to the next to unload their cargoes before attempting to exit the single lane track. Soldiers assembled each artillery piece on the docks prior to loading. This practice ensured that the breech mechanisms, fuses, projectiles, and guns were present and facilitated the final and complete assembly of each gun. To add to the confusion, Plant kept the rail line open for civilian sightseers.96 Congestion had reached its peak.

Two trains stopped on a trestle near the port of Tampa, c. 1898.

Under continuous pressure from Secretary Alger to maintain the pace and load the ships, Shafter relayed in his message on 4 June that he had encountered unforeseen delays due to units arriving late, track congestion, and a lack of facilities. He expressed his frustration at the small throughput capacity in Tampa and reaffirmed his efforts to sail as “early as practical.”97 Finally, the stevedores completed loading equipment at 1100 on 6 June and Shafter ordered that soldier embarkation begin at 1200.98

Both Colonel Humphrey and his assistant, Captain McKay, recalled the loading of the ships as a smooth, coordinated process. Humphrey claimed that it was “carried on speedily and systematically, and continued to completion without regard to hours or fatigue.”99 McKay also recollected the process as orderly and proceeding with no issues.100

However, soldiers’ accounts of the process were vastly different from those in charge at the port. The plan called for an orderly procession of units called forward. Trains were to arrive with troops and baggage together, and soldiers would report to Humphrey for their assigned ship. This process would maintain unit integrity and place the assigned units on the proper ships in accordance with manifests.101 In reality, however, the loading operation was much different. While the initial movement began in an orderly manner, it quickly deteriorated.

Troops prepare to board transport ships at the port of Tampa, 1898.

Soldiers initiated movement throughout the night of 6 June. Shafter reported his hopes to sail by 8 June.102 On the night of 7 June, Shafter received a telegram that the Navy had engaged the forts of Santiago and

If 10,000 men were here, city and fleet would be ours within forty-eight hours. Every consideration demands immediate army movement. If delayed, city will be defended more strongly by guns taken from fleet.103

With that telegram, Shafter’s staff notified the regimental commanders that those units not on ships by morning would remain behind. This order set off a frenzied rush to the ports. The headquarters staff evacuated the Tampa Bay Hotel to its train and found the rail lines congested and immobile.104

Image left: U.S. soldiers in Tampa await the order to board their assigned ships before sailing for Cuba, June 1898. Image right: Members of the 71st New York Volunteer Infantry gather on the dock in Tampa before sailing for Cuba, June 1898.

British war correspondent John Atkins heard the frantic order that “Those who are not aboard by daybreak will be left behind. Leave your tents standing.” He noted the contrast between the long wait in Tampa and the frenzied rush to the docks. Many units abandoned wagons and equipment that were never loaded.105 In the rush, units competed with one another by stealing the abandoned wagons, commandeering train cars, and even hijacking trains.106 One account from 2d Lt. Paul Malone of the 13th U.S. Infantry recounts his unit finding cattle cars with an attached train engine. After finding and rousting the train engineer, they traveled to the port.107

The 9th Infantry seized abandoned wagons and unoccupied freight trains. They interpreted the order as “you fight in Cuba only if you can get to the port and find a ship.”108

A soldier with the 71st New York Volunteer Infantry noted “that no one knew what boat you were going on, what time the boats would come to the pier, or anything else which a little system and some management might have provided.”109

Image left: Paul Malone, pictured here as a brigadier general, c. 1918. Image right: Colonel Roosevelt’s “Rough Riders” arrive at the port of Tampa in June 1898.

Perhaps the most famous story came from Colonel Roosevelt when he described the eventful night as a “scramble.” The Rough Riders followed Shafter’s orders to proceed to the train station at midnight. When no train came for six hours, they seized an engine and some coal cars and backed down the track. Upon arrival to the port, the train dropped them off and the unit sought out Colonel Humphrey for vessel assignment.110 When they finally found him, Humphrey haphazardly assigned them to the Yucatan, previously allocated to the 2d Infantry Division, V Corps and the 71st New York. Roosevelt rushed his men on board faster than the other units and was confronted by Capt. Anthony Bleecker of the 71st New York.111 When asked to surrender the ship, Roosevelt reportedly replied, “Since we have the ship, I think we’ll keep it—much as I would like to oblige you.”112 The 71st spent the next two nights without a vessel, but Humphrey eventually assigned the unit to the Valencia, a newer and more comfortable ship.113 War correspondent George Musgrave noted,

With the capacity of each transport, and the roster of each regiment before him, the youngest officer could have made effective assignment and saved such dire confusion, which took two days to untangle, and entailed much sun exposure and hardship on the soldiers.114

The chaos in the port was influencing the war’s strategic objectives. The confusion caused delays in the timeline of departure, and the War Department felt they were missing their opportunity to win the war quickly and decisively. Shafter found out just prior to loading that there was not enough room for all of his 25,000 soldiers and their equipment.115 The newly converted freighters could not hold the anticipated capacity, even after exceeding the ships’ original capabilities. For example, the Cherokee was equipped for 570 men but carried 1,040.116 Supplies remained on the docks in unopened freight cars. The Gatling gun detachment did not sail due to the limited space.117 Upon assessing the capacity of the ships, Col. Wood received orders he could only take two of his three cavalry squadrons but no horses.118 Not only did the lack of basing facilities slow the tempo of operations, but also the lack of supplies and horses would limit the operational reach of the expedition. All of this notwithstanding, by 1400 on 8 June, most vessels departed the dock and were in position to leave the next morning.

Many authors have written about the Army’s failure to synchronize its movement in the mad dash to the port. This was a failure of command and organization. No one officer was in charge of calling forward troops or of the port’s synchronization. A single leader needed to arrange actions in time, space, and purpose to facilitate the continuous movement and maintain order at the port. The lack of personnel and resources dedicated strictly to deployment management prevented a timely flow of troops and equipment. The single-track line to the Port of Tampa exacerbated the situation by the Army’s reliance on the transportation provided by the Plant Company. The continuous flow of supplies to Tampa City from the rest of the country congested the rail line and disrupted the flow of resources. Logistics planners still had not solved this problem forty days into the operation. The poor transportation infrastructure affected the tempo of the operation creating a culmination point before the expedition was underway. In the postwar investigation, Humphrey testified that he did not know if the train congestion problem was ever unraveled. He also faulted the lack of loading order for the supplies and troops. Humphrey ordered units to load on a first-come, first-served basis, disrupting unit integrity of troops and equipment.119 The process in which Shafter himself telephoned or telegraphed the departing unit from Tampa on their way to the port was a reactive, unplanned process. Shafter simply failed to plan for the movement of 25,000 soldiers down a single railline.

Captain Bleecker at the Creedmoor Rifle Range, Queens, New York, 24 May 1902.

Once the expedition was loaded, Shafter collapsed in exhaustion aboard his ship, the Seguranca, around 1400 on 8 June after having been awake for forty straight hours.120 Responding to the sudden timeline acceleration, he managed to get the bulk of his forces onto ships in a twenty-four hour period. However, an important message arrived from the secretary of war around 1400 stating, “Wait until you get further orders before you sail.”121 Shafter’s aide awakened the commander, who groggily stated that he would fix it in the morning. After Col. Edward McClernand awakened the general a second time to ask for compliance with the order, Shafter roused himself out of his sleep and stated, “God, I should say so,” and he recalled the vessels anchored in the harbor back to the port.122 The cause for the delay was the sighting of a Spanish armored cruiser and torpedo-boat destroyer reported near Nicolas Channel, a straight off the northwest coast of Cuba.123 Shafter immediately ensured all his ships were in the safety of the port under the watchful eye of supporting field guns and escort vessels at the bay’s entrance.124 The expeditionary force returned to its staging posture until further notice.

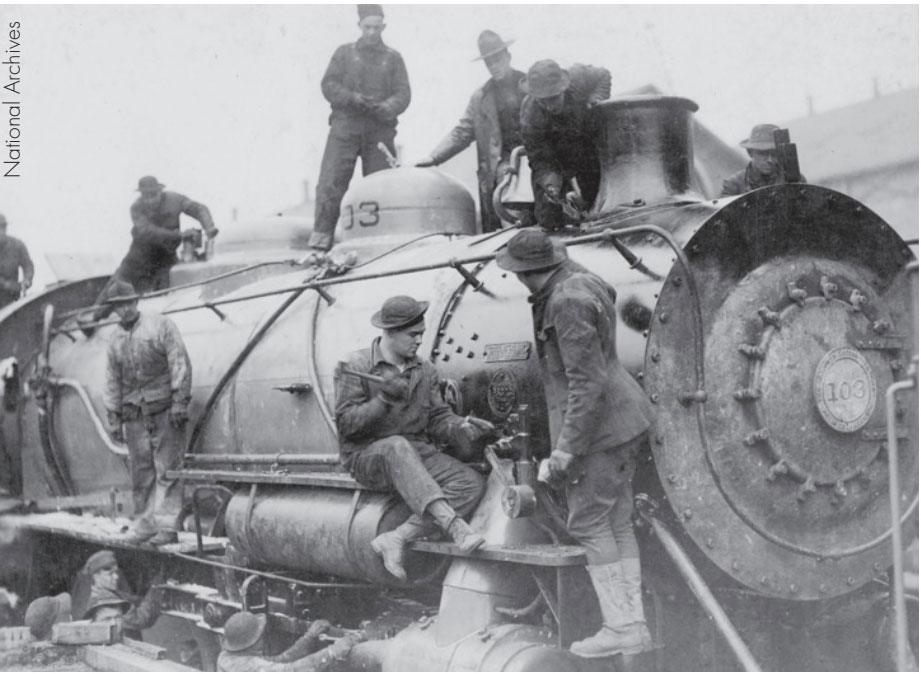

General Shafter observes the unloading of railcars in Tampa.

Shafter decided to house his men aboard the ships in their hot, unventilated compartments to maintain readiness in preparation for the orders to depart. However, construction teams did not build sufficient living facilities onboard the ships to support more than a short journey to Cuba, and the nearest place to camp was back in Tampa, nine miles away. The units unloaded the animals and issued limited passes to the soldiers to disembark the vessels. The soldiers were required to be aboard ship no later than 2100 every night. They also had the option of bathing in the bay.125

From Private Post’s perspective, the conditions were less than ideal. The beds contained only twentyfour inches width of sleeping space. The food on his ship, the Valencia, consisted of corned beef with hardtack cooked on a steam pipe from the engine room. The drinking water was “sluggish fluid mixed with particles of charcoal for health’s sake. It looked like muddy glycerine and tasted like bilgewater.” Aboard the vessels, the men were completely without purpose. Units conducted some landing drills on empty beaches, but even these turned into an excuse to swim. Very few soldiers ventured into town for fear of missing the expedition. This kept alcohol consumption to a minimum for most of the troops, an unintended benefit. The temporary hold, however, created two advantages. The long awaited medical supplies finally arrived, and stevedores loaded them aboard the ships. More importantly, the expedition was actually ready to sail at a moment’s notice.126

On 12 June, after three days of waiting, the War Department issued orders to sail the following day. This time there was no transportation nightmare in loading the ships. The logistics party refueled the ships with coal and water, hoisted the animals on board, and continued loading supplies as the ships individually departed.127 On 13 June, two months after the first units had arrived in Tampa, the ships steamed out of the bay heading for Cuba.

Image left: The expedition flagship Seguranca at the pier in Tampa before departing for Cuba. Image right: Grenville Dodge, c. 1900.

After the Spanish-American War’s conclusion, public criticism erupted over the lack of medical support during the conflict. The press directed its outrage at what it deemed criminal neglect in camps, hospitals, and during transit. President McKinley, sensing political pressure, appointed retired major general Grenville Dodge to chair a commission that would come to bear his name. The Dodge Commission conducted its investigation between 26 September 1898 and 9 February 1899.128 The report produced by the commission, which included interviews with eyewitnesses and firsthand accounts, provided valuable insight into the logistical process and problems encountered at Tampa.

Conclusions from the report noted four major deficiencies related to the deployment operation. First, the Army effectively staffed the quartermaster department to support an army of peacetime proportions, not a force exceeding 25,000. Second, the congestion at Tampa was due to the lack of administrative oversight in the quartermaster and railroad sections. Third, there was a total failure of planning for ship transport capacity that decreased the fighting force by 8,000 soldiers and its ambulance carrying capability. Finally, there needed to be a division of labor between the quartermaster and transportation departments instead of both working similar issues simultaneously.129

Implications for World War I Operations

The lessons learned from the failures of this deployment impacted future operations. The Army had failed to establish adequate basing, its operational reach was hampered by logistical and transport problems, and its tempo was disrupted by a lack of command oversight on the docks, as well as by conflicting and confusing orders—all of which were detrimental to the mobilization process. These deficiencies were corrected and the deployment process improved at debarkation points in New York City, and elsewhere, during World War I.

Edward McClernand, pictured here as a brigadier general, c. 1912.

Base selection is critical to support contemporary deployments. The War Department chose Tampa because of its proximity to Cuba and because it met the minimum logistical requirements, including two railroad tracks entering the town, a port that could hold a small number of ships, and a projected water supply for the soldiers. Even t houg h Ta mpa had met t hese minimum requirements, there was not enough additional planning for the needs of 25,000 incoming troops. World War I planners understood the limitations of a port like Tampa and chose the Port of New York as the embarkation facility. The port in New York was one of the largest in the world and possessed more than ample facilities—railroads, docks, housing, food and water supplies—to mobilize millions of soldiers. The port could expand as needed to meet increased requirements, unlike Tampa’s inability to grow effectively.

Unity of command is a principle critical to managing throughput of basing operations. A single commander for the logistics aspect of deployment allows solitary focus on controlling and operating port deployments. This commander has the ability to adjust resources as necessary, control movements in the deployment area, and arrange support for units in transition.130 In Tampa, there was no single commander for the deployment operation. General Shafter was responsible for the overall operation, but at no time over the forty-day period did he take control of the process to relieve the congestion. Colonel Humphrey was responsible for the staging and loading of supplies along with the arrangement of soldiers on transports once called forward. However, his responsibility was limited to the port area. Then—2d Infantry Division commander and future Brig. Gen. Arthur Wagner stated in his memoirs that the expedition commander shou ld have granted authority to a single officer and charged him with the loading process.131 At no time was there a single point of contact for the deployment process to task and shift resources for alleviating congestion.

The Port of New York in World War I was vastly different. Unity of command was assigned to ports, ensuring that resources could be adequately allocated. Maj. Gen. J. Franklin Bell commanded the New York port of embarkation and managed all movement through the port.132 American planners understood that “adequate and clear lines of communications were critical to organizing and sustaining large-unit operations.”133 Bell used his command authority and robust staff to manage port flow. This unity of command stands in contrast to Shafter’s leadership—he lacked the institutional knowledge to assign a deployment commander with a large enough staff to manage port operations.

Military planners traditionally associate the tempo of operations to combat-related activities. However, efficient and effective mobilization of units requires a steady pace and rhythm to bring soldiers into combat at their optimal performance. Tampa demonstrated tempo with varying peaks and valleys. Initially, the War Department sent 5,000 soldiers to Cuba to support the insurgency, followed by a forty-day lull while troops mustered in Florida. Shafter ordered a mad dash to the transports only to wait for three days in miserable conditions aboard hot, cramped vessels. This entire process contributed to a degraded fighting force. The deployment process at Tampa diminished combat preparedness, and the force did not arrive in Cuba in an optimal state of readiness.

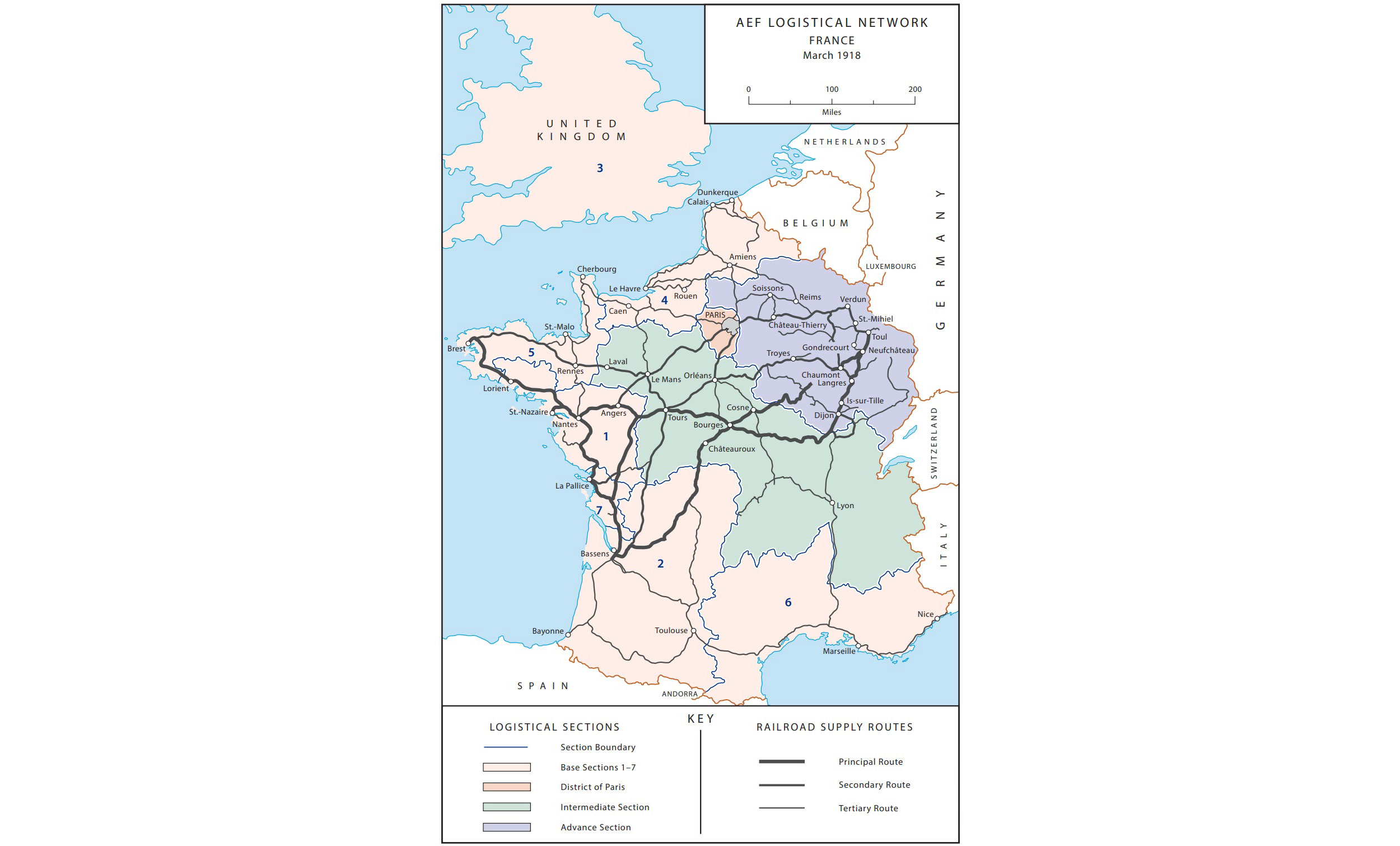

The pace of deployment is maintained through the Army adage, “slow is smooth, and smooth is fast.” This momentum can be facilitated using synchronization, which manages the timing of supply in the correct order and coordinates with supporting activities “to ensure the tempo of deployment is uninterrupted.”134 Soldiers at the Port of New York performed synchronization activities admirably after recognizing a train congestion issue that clogged the ports. The decentralized system of railroad transportation created a backlog of railcars leading into New York.135 However, the government established the Shipping Control Committee in February 1918, which organized a single system to coordinate the flow from unit mobilization stations to the Port of New York, to transport overseas, and finally onto the French ports. The Operations Division in Washington performed synchronization oversight coordinating with the Railroad Administration, the Port of New York, the U.S. Navy, and the British Ministry of Shipping. The detailed planning synchronized the flow of movement in direct contrast to the activities in Tampa. New York was not without its difficulties and failings, as machinery breakdowns, labor disputes, and fuel shortages often delayed sailings and disrupted the massive mobilization. However, the New York operation managed to move almost one hundred times the number of men as the Army did in Tampa, and with far fewer issues.136

Library of Congress General Bell, c. 1917

Operational reach and tempo are mutually supportive and stem from establishing proper basing at the beginning of operations. Basing establishes the operational reach for follow-on missions. Planners originally designated Tampa as a temporary port facility established for the rapid deployment of soldiers to Cuba. However, the mission evolved, and 25,000 troops mobilized and reported to Tampa without the required sustainment resources on-site. This created two single points of failure: rail capacity and sea transportation. The lack of rail capacity disrupted momentum in loading the vessels. Congestion led to confusion with assembling rations and field guns for eventual deployment. The shortage of vessels created a storage capacity problem and reduced the number of soldiers able to depart on the expedition. These shortfalls resulted in the inability to transport all combat power, leaving 8,000 soldiers and important supplies, such as ambulances and cavalry horses, on the docks. These two assets were crucial to maintaining momentum.

Unit integrity is the movement of soldiers and associated equipment together on a common platform to simplify the deployment process, leverage the chain of command, and increase training opportunities. While the intent in Tampa was to keep units together, they arrived at the ports with directions to board ships assigned to other units. The lack of understanding of vessel capacity and capability unnecessarily separated units from their equipment. Most notably, the cavalry sailed to Cuba without its horses and fought as infantrymen, and the medical soldiers sailed on different vessels than did their ambulances. In World War I, the Army solved unit integrity issues during the troop movement phase by issuing soldiers equipment in New York and having them carry it directly aboard the ships. This eliminated the task of loading gear at home station and tracking it throughout the process. Supply activities consisted of 138 warehouses with ample supply of materiel to issue transitioning soldiers.137

Balance ensures the correct support system is in place to process deploying units, thereby extending operational reach.138 An excess of sustainers creates confusion while a shortage creates backlogs in the system. Colonel Humphrey was not only in charge of the quartermaster department at Tampa, but assigned as the chief quartermaster of the expedition. In his testimony, Humphrey stated, “I did not see how I could perform the duties, as I was there on other business.”139 There was no dedicated staff, other than the hired stevedores, to facilitate onward movement and extend operational reach. The result was that Tampa became a port of ineffectiveness once the ships sailed. The remaining supplies, food stocks, horses, and ambulances did not rejoin the expedition. The second compounding factor was that the privatized railroad eliminated all balance from military mobilization. Without control and synchronization of the railroads, the expedition relied on the Plant Company to transport freight and passengers the final nine miles to the port, an arrangement that was detrimental to the mobilization effort.

In 1918, the Army solved these problems by dedicating support infrastructure solely to the deployment process. The Port of New York had more than 2,500 officers assigned whose mission was to facilitate the movement of forces.140 The federal government mitigated rail congestion by seizing the railroad infrastructure under the National Defense Act of 1916 along with taking over the North-German Lloyd and HamburgAmerican Steamship companies.141 Federalized control of transportation assets eliminated friction between civilian and government agencies.

Conclusion

The Spanish-American War required an immediate mobilization of men and equipment. The original plan of sending 5,000 troops through Tampa escalated quickly to 25,000 men as strategic objectives shifted from supporting insurgents to fighting a full-fledged war against the Spanish in Cuba. Clausewitz states that an army “remains dependent on its sources of supply and replenishment,” that bases “constitute the basis of its existence and survival,” and that the “army and base must be conceived as a single whole.”142

Operations in Tampa failed to connect the strategic with the tactical actions of sustainment in three areas: basing, tempo, and operational reach.

Clausewitz posits, “No one starts a war . . . without first being clear in his mind what he intends to achieve by that war and how he intends to conduct it. The former is the political purpose; the latter its operational objective.” This principle establishes the course of the war in “scale of means and effort” that influences an operation “down to the smallest operational detail.”143 Clausewitz argued for clear war plans, a reasoning that permeates into the logistics of supplying and transporting an army into theater to meet political objectives by linking tactical actions. He asserts that maintenance and supply are critical to sustaining an army. He contends that subsistence by means of depots is one of four ways to provide for a force, and the base of operations is critical to its survival.144 This is a holistic approach to sustaining the operational reach and tempo. The flow of men and equipment to the field of battle is paramount, and “one must never forget that it is among those that take the time to produce a decisive effect.”145 Clausewitz understood the importance of sustainment as laying the foundation for the political and military end state.

The failure to link strategic and tactical goals, the changing guidance from the War Department, and insufficient resources to maintain deployment momentum created unnecessary disruptions to operational capabilities. By 1918, the evolution of planning and executing mobilizations saw great gains in synchronizing and integrating unit flow from home station to France. This was due to having a single commander in New York and supporting forces with the sole mission of deploying units through the port. The War Department learned to oversee holistic transportation plans through rail, port, and sea, resulting in massive numbers of soldiers, along with all supporting materiel, being successfully moved around the country and deployed overseas.146

Charles Johnson Post, Embarking for Cuba, Port Tampa, Florida, June 1898

The movement of troops and equipment from countless locations within the country to a central port of embarkation was required for follow-on movement to the war zone. New York City was the primary hub for overseas transit to France. Created in 1917, the Embarkation Service was the central organization tasked with overseeing all ports of departure in the United States. The New York port of embarkation employed 2,500 officers working in various roles at piers, staging camps, and hospitals. New York Harbor and its subports deployed 1,798,000 soldiers by the war’s end—with a peak of 51,000 troops dispatched overseas in one day—which exceeded all previous single-port records.147

Commanded by General Bell, the New York Port of Embarkation controlled movement operations as a single system, flowing a total of 5,130,000 tons of equipment through Armistice Day.148 In comparison to deployment operations in Tampa, the ports of New York were a model of efficiency and control during World War I.

Author’s Note The author would like to extend special thanks to Dr. Ricardo Herrera, who was instrumental during the writing process and encouraged the author to submit this article for publication.

Footnotes

1 Army Doctrine Reference Publication (ADRP) 3–0 discusses ten elements of operational art. Basing, tempo, and operational reach are all critical to pursuing “strategic objectives, in whole or in part, through the arrangement of tactical actions in time, space, and purpose.” ADRP 3–0, Unified Land Operations (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2012), pp. 4-1–4-3.

2 Field Manual (FM) 3–35 states that reception, staging, onward movement, and integration “is designed to rapidly combine and integrate arriving elements of personnel, equipment, and materiel into combat power that can be employed by the combatant commander.” Moreover, four principles underpin the reception, staging, onward movement, and integration (RSOI) process: unity of command, synchronization, unit integrity, and balance. FM 3–35, Army Deployment and Redeployment (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2010), pp. 4-1–4-2.

3Walter Millis, The Martial Spirit: A Study of Our War with Spain (Boston, Mass.: Riverside Press, 1931), pp. 1–31. See John Lawrence Tone, War and Genocide in Cuba, 1895–1898 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008) on the Spanish policy of reconcentration and prosecution of the war against Cuban insurgents.

4 G. J. A. O’Toole, The Spanish American War (New York: W. W. Norton, 1984), p. 20.

5 O’Toole, The Spanish American War, pp. 20–21.

6 Millis, The Martial Spirit, pp. 116–17.

7 John M. Thurston, “Senate Speech March 24, 1898,” in Patriotic Eloquence Relating to the Spanish-American War and Its Issues, ed. Robert Fulton and Thomas Trueblood (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1903), pp. 304–08.

8 Richard Titherington, A History of the Spanish American War of 1898 (New York: D. Appleton, 1900), p. 105.

9 Frank Freidel, The Splendid Little War (Boston, Mass.: Little, Brown and Company, 1958), p. 38.

10 A. C. M. Azoy, CHARGE! The Story of the Battle of San Juan Hill (New York: Longman’s, Green and Company, 1961), p. 38.

11 Freidel, The Splendid Little War, p. 60.

12 Graham A. Cosmas, An Army for Empire: The United States Army in the Spanish-American War (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1971), p. 187.

13 Edward J. McClernand, “The Santiago Campaign,” in The Santiago Campaign, ed. Joseph T. Dickman (Richmond, Va.: Williams Printing Company, 1927), p. 3.

14 Kenneth E. Hendrickson, The Spanish-American War (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood, 2003), p. 10.

15 Cosmas, An Army for Empire, p. 187.

16 Russell A. Alger, The Spanish-American War (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1901), p. 65.

17 Ibid., p. 69.

18 FM 3–35 states reception, staging, and onward movement are designed “to rapidly combine and integrate arriving elements of personnel, equipment, and materiel into combat power that can be employed by the combatant commander.” FM 3–35, Army Deployment and Redeployment, p. 4-1.

19 ADRP 3–0 defines tempo as “the relative speed and rhythm of military operations over time with respect to the enemy.” ADRP 3–0, Unified Land Operations, pp. 4–7.

20 ADRP 3–0 defines operational reach as “the distance and duration across which a joint force can successfully employ military capabilities.” This element of operational art relates to the ability to “create, protect, and sustain a force. Ibid., pp. 4–5.

21 Carl von Clausewitz, On War, trans. and ed. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1984), pp. 343–44.

22 Cosmas, An Army for Empire, p. 126.

23 Hendrickson, The Spanish-American War, p. 28.

24 Herbert H. Sargent, The Campaign of Santiago de Cuba, vol. 1 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1907), p. 108.

25 Ibid., pp. 89–90.

26 Ibid., p. 114.

27 Correspondence Relating to the War with Spain, Vol. 1 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1902), p. 9.

28 Cosmas, An Army for Empire, p. 194.

29 Wayne H. Morgan, America’s Road to Empire: The War with Spain and Overseas Expansion (1965; repr., New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1966), p. 71.

30 Cosmas, An Army for Empire, p. 194.

31 James A. Huston, The Sinews of War: Army Logistics, 1775–1953 (Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, 1997), p. 280.

32 John D. Miley, In Cuba with Shafter (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1899), pp. 1–4.

33 Huston, The Sinews of War, p. 280.

34 Report of the Commission Appointed by the President to Investigate the Conduct of the War Department with Spain, 56th Cong., 1st sess., 1900, S. Doc. 221, vol. 7, p. 3638.

35 Miley, In Cuba with Shafter, pp. 9–10.

36 FM 3–35 defines the reception process as “unloading personnel and equipment from strategic transport assets, managing port marshalling areas, transporting personnel, equipment, and materiel to staging areas, and providing logistics support services to units transiting the port of debarkation.” FM 3–35, Army Deployment and Redeployment, p. 4-1.

37 Millis, The Martial Spirit, p. 241.

38 Cosmas, An Army for Empire, p. 195.

39 Ibid., pp. 170–71.

40 Charles Johnson Post, The Little War of Private Post (Boston, Mass.: Little, Brown and Company, 1960), pp. 68–69.

41 Dale L. Walker, The Boys of ‘98: Theodore Roosevelt and the Rough Riders (New York: Tom Doherty Associates, 1998), p. 143.

42 Theodore Roosevelt, The Rough Riders (1899; repr., Williamstown, Mass.: Corner House, 1979), pp. 53–54.

43 David F. Trask, The War with Spain in 1898, (New York: Macmillan, 1981), p. 184.

44 Joseph Wheeler, The Santiago Campaign 1898 (Boston, Mass.: Rockwell and Church, 1898), pp. 5–6.

45 Charles H. Brown, Correspondents’ War (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1967), p. 212.

46 Miley, In Cuba with Shafter, p. 11.

47 Cosmas, An Army for Empire, pp. 130–31.

48 Huston, The Sinews of War, p. 280.

49 Alger, The Spanish-American War, p. 65.

50 Freidel, The Splendid Little War, p. 60.

51 Cosmas, An Army for Empire, p. 195.

52 Huston, The Sinews of War, p. 281.

53 Cosmas, An Army for Empire, p. 195.

54 David Rutenberg and Jane Allen, eds., The Logistics of Waging War: American Logistics 1774–1985, Emphasizing the Development of Airpower (Gunter Air Force Station, Ala.: Air Force Logistics Management Center, 1985), p. 49.

55 Huston, The Sinews of War, p. 281.

56 FM 3–35 defines the staging process as “organizing personnel, equipment, and basic loads into movement units; preparing the units for onward movement; and providing logistics support for units transiting the staging area.” FM 3–35, Army Deployment and Redeployment, p. 4-1.

57 Thomas J. Vivian, The Fall of Santiago (New York: R. F. Fenno, 1898), p. 74.

58 Sargent, The Campaign of Santiago de Cuba, pp. 112–23.

59 Morgan, America’s Road to Empire, p. 70.

60 Cosmas, An Army for Empire, p. 129.

61 Huston, The Sinews of War, p. 283.

62 Brown, Correspondents’ War, p. 271.

63 Dwight E. Aultman, “Personal Recollections of the Artillery at Santiago, 1898,” in The Santiago Campaign, ed. Joseph T. Dickman (Richmond, Va.: Williams Printing Company, 1927), p. 184.

64 Huston, The Sinews of War, p. 279.

65 Alger, The Spanish-American War, p. 74.

66 Cosmas, An Army for Empire, p. 197.

67 C. D. Rhodes, “The Diary of a Lieutenant,” in The Santiago Campaign, ed. Joseph T. Dickman (Richmond, Va.: Williams Printing Company, 1927), p. 335.

68 B. T. Simmons and E. R. Chrisman, “The Sixth and Sixteenth Regiments of Infantry,” in The Santiago Campaign, ed. Joseph T. Dickman (Richmond, Va.: Williams Printing Company, 1927), p. 68.

69 Huston, The Sinews of War, p. 282.

70 Harvey Rosenfeld, The Diary of a Dirty Little War: The Spanish-American War of 1898 (Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 2000), p. 94.

71 Trask, The War with Spain, p. 182.

72 John Black Atkins, The War in Cuba: The Experiences of an Englishman with the United States Army (London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1899), p. 51.

73 Rosenfeld, The Diary of a Dirty Little War, p. 85.

74 Huston, The Sinews of War, p. 279.

75 Rosenfeld, The Diary of a Dirty Little War, p. 96.

76 Huston, The Sinews of War, p. 279.

77 Valery Havard, “The Medical Corps at Santiago,” in The Santiago Campaign, ed. Joseph T. Dickman (Richmond, Va.: Williams Printing Company, 1927), p. 207.

78 Trask, The War with Spain, pp. 160–61.

79 Rosenfeld, The Diary of a Dirty Little War, p. 99.

80 Walker, The Boys of ‘98, p. 138.

81 Cosmas, An Army for Empire, pp. 169–72.

82 Rosenfeld, The Diary of a Dirty Little War, p. 94.

83 Walker, The Boys of ‘98, p. 140.

84 A. B. Feuer, The Santiago Campaign of 1898: A Soldier’s View of the SpanishAmerican War (Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 1993), pp. 15–16.

85 Post, The Little War of Private Post, p. 71.

86 Freidel, The Splendid Little War, p. 40.

87 Roosevelt, The Rough Riders, p. 55

88 Walker, The Boys of ‘98, p. 137.

89 FM 3–35 defines onward movement as “moving units from reception facilities and staging areas to tactical assembly areas or other theater destinations; moving non-unit personnel to gaining commands; and moving sustainment supplies to distribution sites.” FM 3–35, Army Deployment and Redeployment, p. 4-1.

90 Miley, In Cuba with Shafter, pp. 15–16.

91 Correspondence Relating to the War with Spain, p. 16.

92 Miley, In Cuba with Shafter, p. 18.

93 Ibid., pp. 19–23.

94 Huston, The Sinews of War, p. 282.

95 Freidel, The Splendid Little War, p. 60.

96 Miley, In Cuba with Shafter, pp. 23–24.

97 Correspondence Relating to the War with Spain, p. 25.

98 Huston, The Sinews of War, p. 283.

99 Charles F. Humphrey, “The Quartermaster’s Department at Santiago de Cuba,” in The Santiago Campaign, ed. Joseph T. Dickman (Richmond, Va.: Williams Printing Company, 1927), p. 196.

100 Report of the Commission, vol. 6, pp. 2,655–2,678.

101 Miley, In Cuba with Shafter, p. 25.

102 Correspondence Relating to the War with Spain, p. 28.

103Ibid., pp. 29–30.

104 Miley, In Cuba with Shafter, p. 32.

105 Atkins, The War in Cuba, pp. 63–69.

106 Hendrickson, The Spanish-American War, p. 30.

107 Paul B. Malone, “The Thirteenth U. S. Infantry in the Santiago Campaign,” in The Santiago Campaign, ed. Joseph T. Dickman (Richmond, Va.: Williams Printing Company, 1927), pp. 92–93.

108 Edwin V. Bookmiller, “The Ninth U. S. Infantry,” in The Santiago Campaign, ed. Joseph T. Dickman (Richmond, Va.: Williams Printing Company, 1927), p. 60.

109 George R. Van Dewater, “The Seventy First Regiment, New York Volunteers at Santiago de Cuba,” in The Santiago Campaign, ed. Joseph T. Dickman (Richmond, Va.: Williams Printing Company, 1927), p. 129.

110 Roosevelt, The Rough Riders, pp. 55–59.

111 Freidel, The Splendid Little War, pp. 67–68.

112 Feuer, The Santiago Campaign, pp. 16–17.

113 Freidel, The Splendid Little War, pp. 67–68.

114 George C. Musgrave, Under Three Flags in Cuba: A Personal Account of the Cuban Insurrection and Spanish-American War (Boston, Mass.: Little, Brown and Company, 1899), p. 260.

115 Cosmas, An Army for Empire, p. 196.

116 Rhodes, The Santiago Campaign, p. 335.

117 Azoy, CHARGE!, pp. 55–57.

118 Walker, The Boys of ‘98, p. 143.

119 Report of the Commission, vol. 7, pp. 3,639–3,652.

120 McClernand, The Santiago Campaign, p. 6.

121 Correspondence Relating to the War with Spain, p. 31.

122 McClernand, The Santiago Campaign, p. 6.

123 Correspondence Relating to the War with Spain, p. 31.

124 Miley, In Cuba with Shafter, pp. 34–35.

125 Ibid., pp. 34–37.

126 Post, The Little War of Private Post, pp. 77–93.

127 Miley, In Cuba with Shafter, p. 40.

128 Vincent J. Cirillo, Bullets and Bacilli: The Spanish-American War and Military Medicine (Piscataway, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2004), pp. 100–103.

129 Report of the Commission, vol. 1, pp. 147–48.

130 130. FM 3–35, Army Deployment and Redeployment, p. 4-1.

131 Arthur Wagner, The Santiago Campaign (Kansas City, Kans.: Franklin Hudson Publishing, 1906), pp. 23–24.

132 Huston, The Sinews of War, p. 345.

133 Michael Matheny, Carrying the War to the Enemy: American Operational Art to 1945 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2011), p. 29.

134 FM 3–35, Army Deployment and Redeployment, p. 4-1.

135 Rutenberg and Allen, The Logistics of Waging War, p. 65.

136 Huston, The Sinews of War, pp. 347–48.

137 Ibid., p. 146.

138 FM 3–35, Army Deployment and Redeployment, p. 4-2.

139 Report of the Commission, vol. 7, pp. 3638–3639.

140 Huston, The Sinews of War, p. 346.

141 Rutenberg and Allen, The Logistics of Waging War, 65; Huston, The Sinews of War, p. 345.

142 Clausewitz, On War, p. 341.

143 Ibid., p. 579.

144 Ibid., pp. 332–38.

145 Ibid., p. 344.

146 Rutenberg and Allen, The Logistics of Waging War, p. 65.

147 Huston, The Sinews of War, pp. 345–48. 148.

148 Ibid.

"Get the Boys Home—Toot Sweet."

A Private's-Eye Biew of World War I Demobilization

By Crant T. Harward

Army History, No. 115 (Spring 2020)

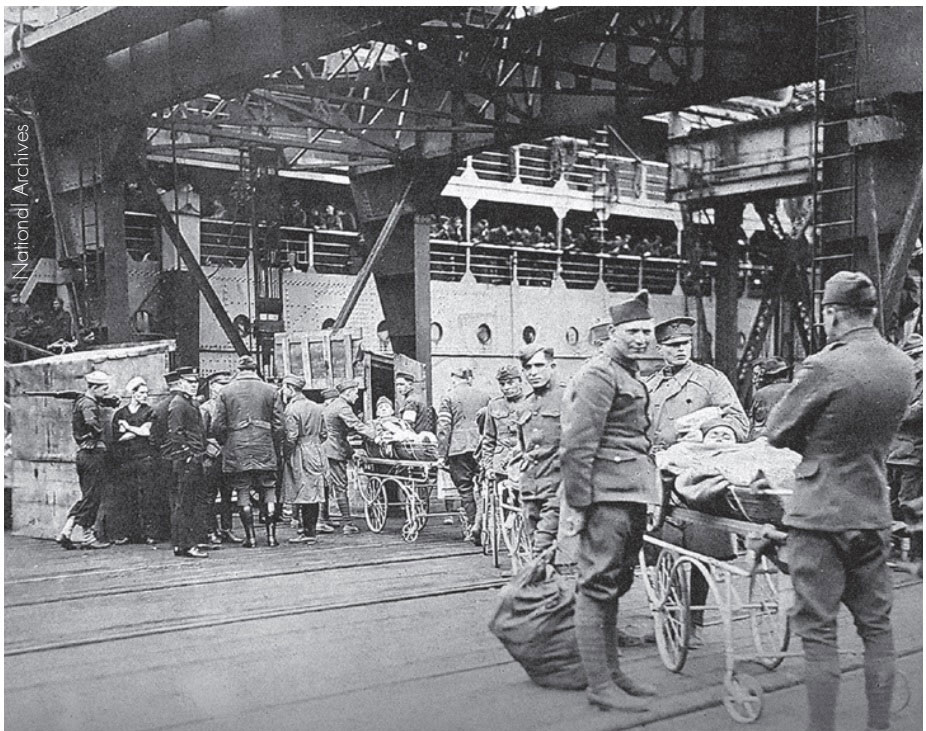

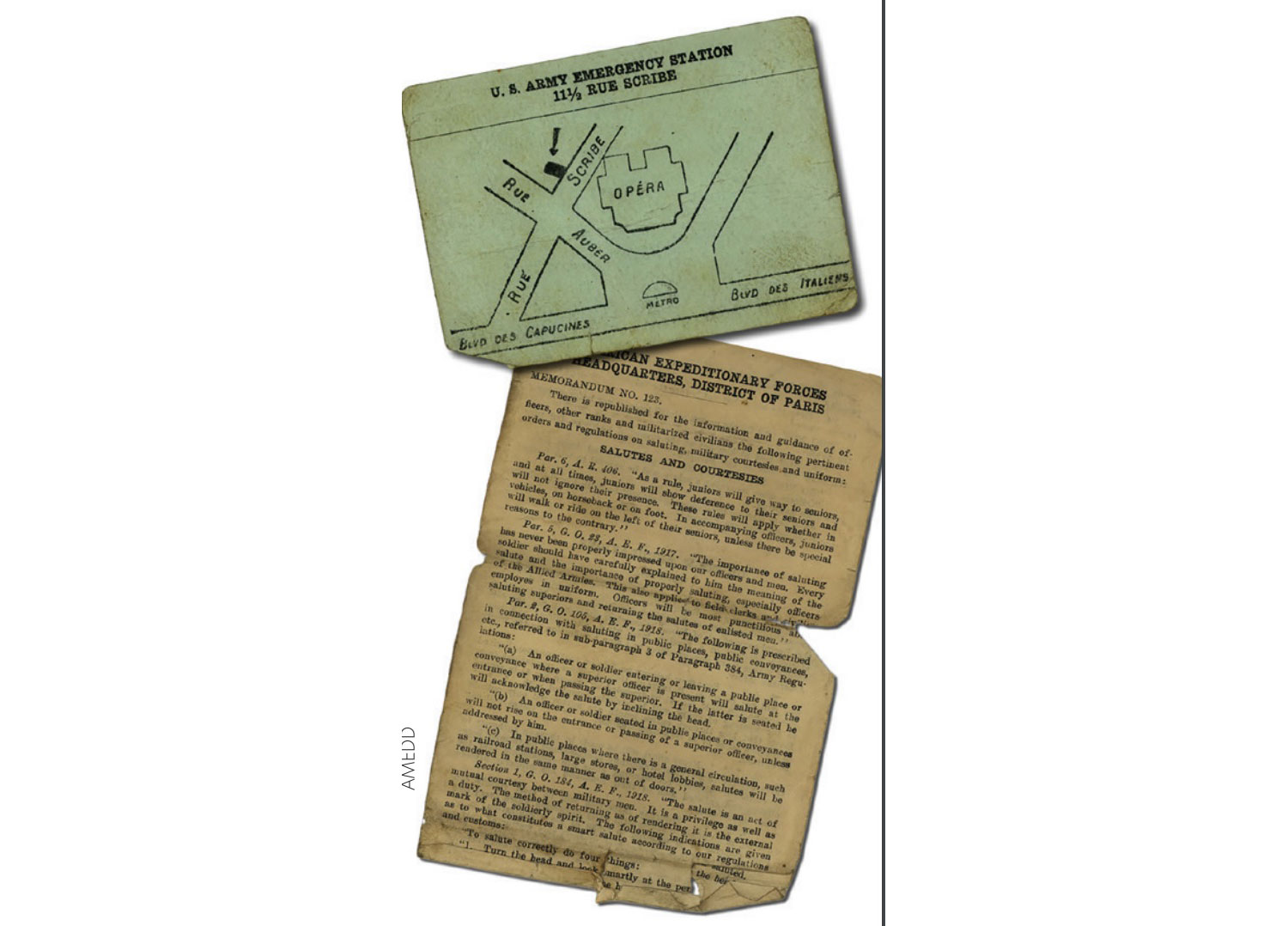

A soldier prepares to embark for the voyage home, c. 1918.

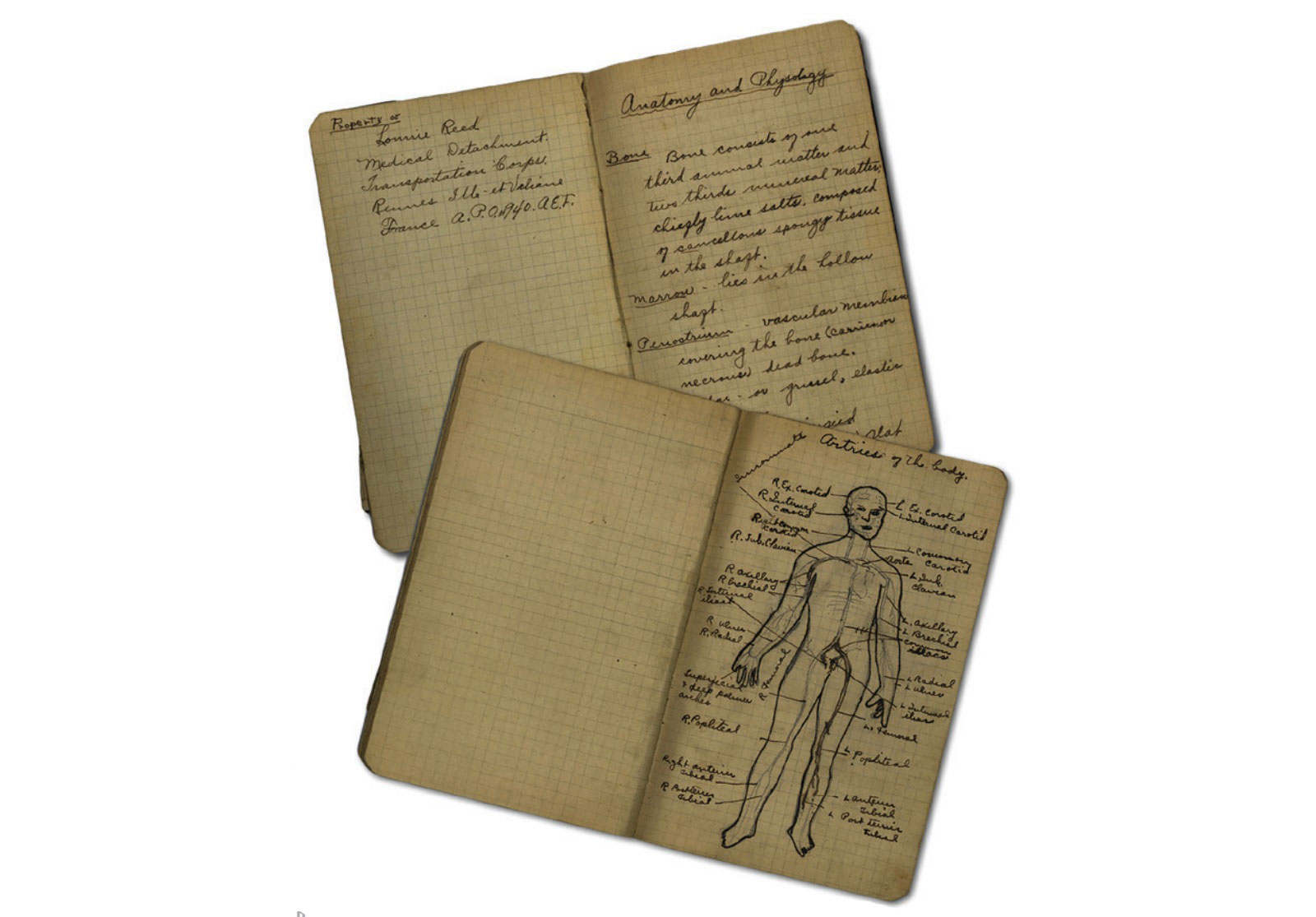

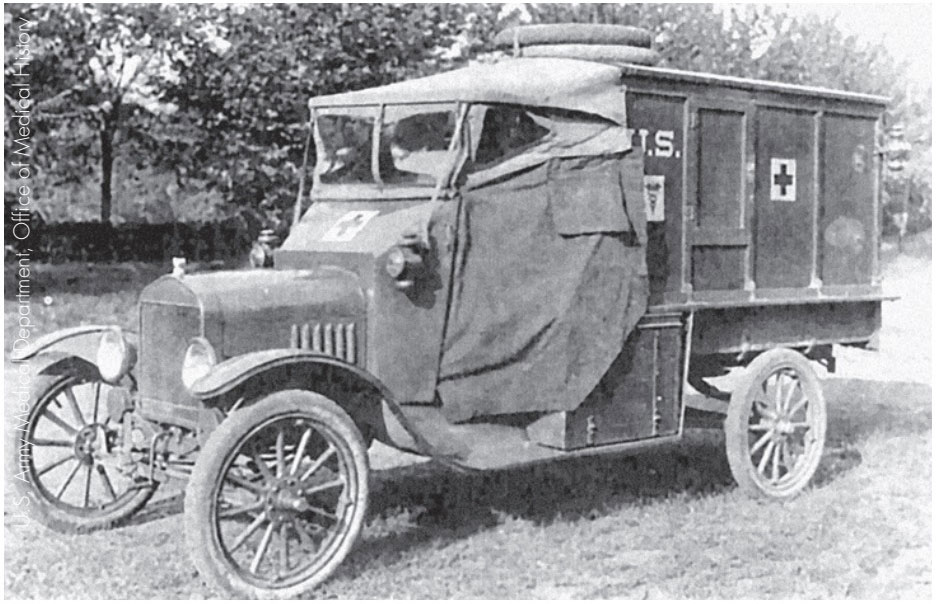

"The papers here are printing headlines ‘get the boys home– toot sweet’ but there is nothing definate as to going home yet. All the talk is of being sent to Russia,” Pfc. Alonzo E. Reed Jr. wrote his mother on 2 February 1919.1 Lonnie (as family and friends called him) used “toot sweet,” the anglicized French phrase tout de suite meaning “right now,” popularized by doughboys in France. His letter illustrates the conundrum facing the U.S. Army on the Western Front following the Armistice. The American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) needed to be ready to fight if peace negotiations collapsed and also to support an ongoing Allied intervention in the civil war in Russia, but they also had to demobilize rapidly because the American public expected soldiers to return from overseas “toot sweet.”

Lonnie served with a railroad regiment in France that helped transport most of the AEF to ports for home. His collection of letters, stored at the archives of the U.S. Army Medical Department (AMEDD) Center of History and Heritage, provides a unique private’s-eye view of the AEF’s demobilization a century ago. This article covers Lonnie’s military service between May 1918 and November 1919 and uses his correspondence to highlight various aspects of Army demobilization.

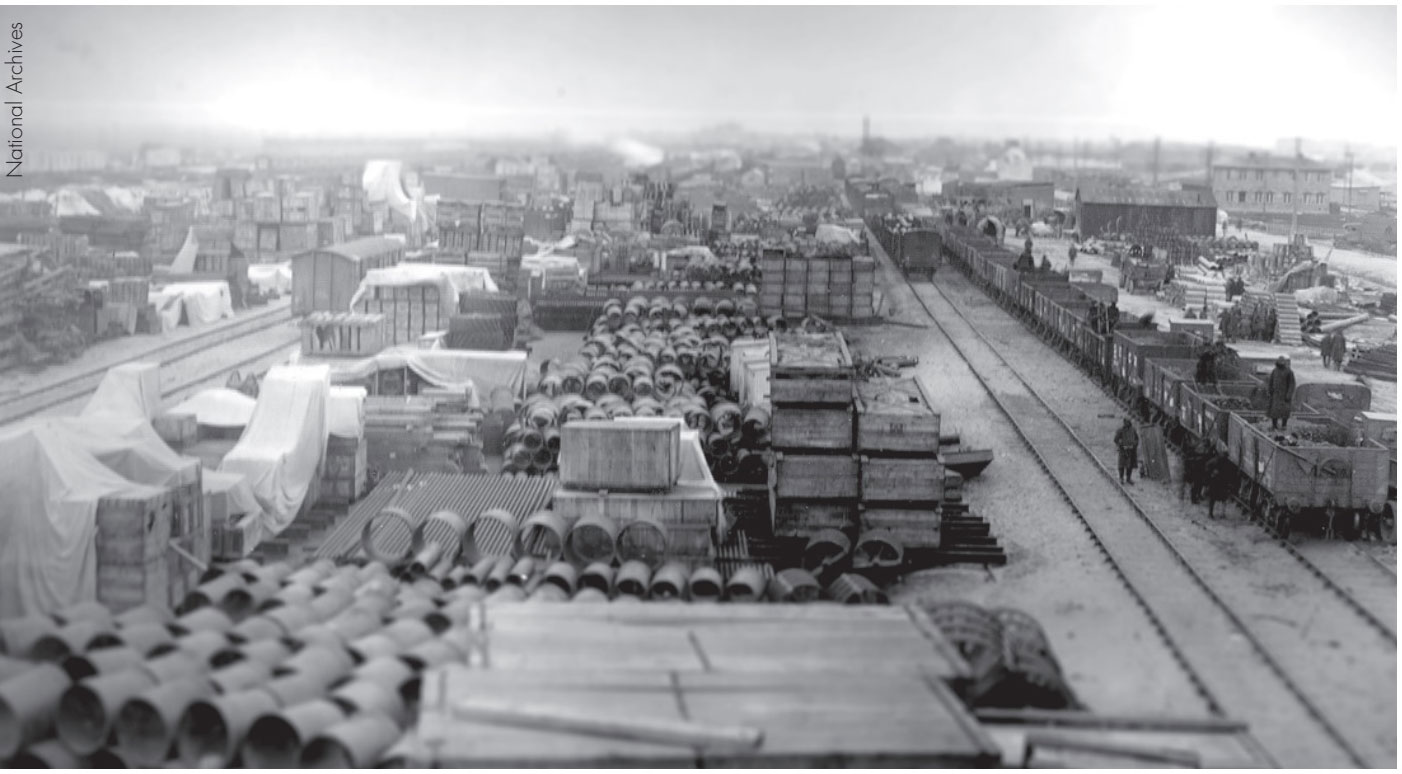

Troops board a train to a port of embarkation, 7 January 1919.