Army Helicopter Operations In Antarctica: Eight Years of Support

By Thomas L. Orr Major, USA U.S. Naval Support Force, Antarctica

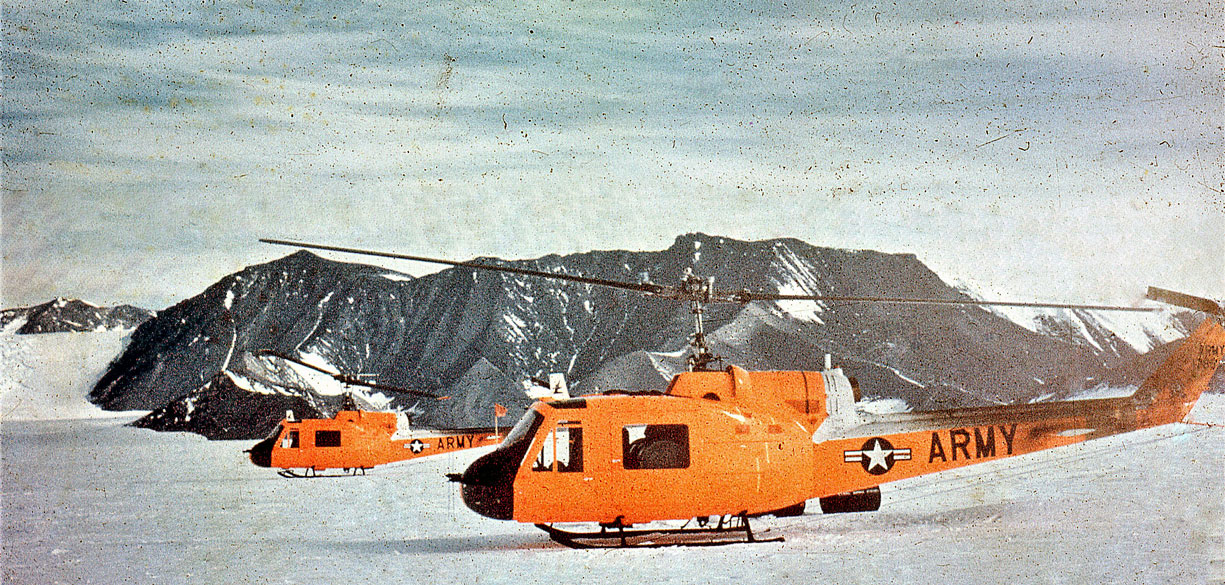

In February of 1963, this helicopter was one of three to make the first rotary wing flight to the geographic South Pole.

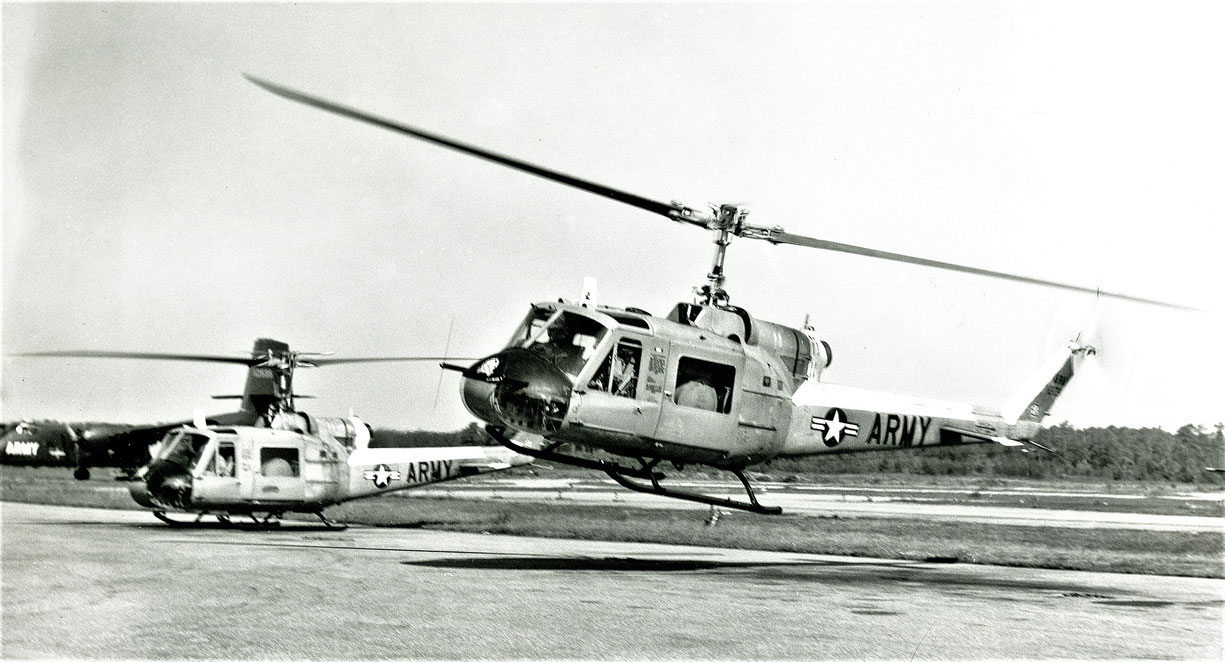

In January 1969, the U.S. Army Aviation Detach- ment (Antarctica Support) returned from the Antarctic to the United States for the last time. This unit, equipped with the UH series of Bell "Iroquois" turbine-powered helicopters, had since Deep Freeze 62 played a major role in support of field work, especially that conducted at remote campsites. In eight years of deployment, the detachment flew over 3,000 hours in support of the antarctic program and proved beyond all doubts the usefulness of the turbine helicopter in the antarctic environment.

Topo North and South

In 1961, in response to a request from the Navy to provide helicopter support for Topo North and South—a U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) topographic survey of the Victoria Land coast—the U.S. Army Transportation Board, Ft. Eustis, Virginia formed Task Detachment No. 3, consisting of nine men and two U-I-1B helicopters. The choice of the turbine-powered UH—1B for this project seemed to be a good one. Although never before used in a polar environment, it had several significant advantages over the gasoline-powered piston-engine helicopters used by the Navy. The UH—1B could operate at altitudes up to 13,000 feet, had an average payload of over 2,000 pounds, required little or no preheating for low-temperature starts, and could be easily transported by LC—130 and Air Force Military Airlift Command (MAC) aircraft. These advantages were, however, at least partially, offset by the lack of coldweather operational experience on the part of the Army crews, the limited range of the UH—1B, and lack of maintenance and repair-parts experience in operating the aircraft in polar regions.

Topo North and South, as originally planned, envisioned two major survey efforts.1 Topo South, to be conducted first, called for a survey of the Transantarctic Mountains from McMurdo Sound south to the head of the Beardmore Glacier. This portion of the project was to be supported completely by air.

Topo North was a similar survey north to Cape Adare, except that icebreakers would be used as launching platforms for the helicopters. The entire survey was some 1,500 miles in length, approximately the distance from Washington, D.C. to the southern tip of Florida, and covered an area one-third again as large as New England. Numerous landings at altitudes above 10,000 feet under hazardous conditions would be required to obtain the necessary topographical data.

U.S. Geological Survey engineers making measurements after being ferried to field site by helicopter. U.S. Navy Photo"

The Army detachment arrived at McMurdo on October 21, 1961 and, after a short period for test flights and indoctrination, Topo South was begun. The project was a success from the start. The UH—1B Iroquois, like the LC—130 Hercules, proved to be remarkably well suited to antarctic operations. With the assistance of Navy aircraft, which established fuel caches along the traverse route and moved camp equipment from one site to the next, all the objectives of the survey were completed by December 6. Based upon their experience in Topo South, neither the Army pilots nor the USGS engineers agreed with the plan to base the helicopters aboard the icebreakers for Topo North. Therefore, when the icebreakers were forced to return to New Zealand because of damage sustained during channelbreaking operations, the original plan was discarded, and Topo North became a land-based operation. The survey was begun on December 17 and completed by January 12

In all, the UH—111s flew 182 hours in support of Topo North and South. A total of 68 sites were occupied, many of them at elevations above 10,000 feet (the highest landing was on Mt. Usher—13,500 feet). Accurate topographic data were obtained for over 100,000 square miles of previously unmapped, or only partly charted, terrain.

Although the UH—lBs were able to fly on only 14 of the 57 days spent on the survey, with fuel shortages and poor weather causing most of the delays, Topo North and South was completed a month ahead of schedule.

Topo North and South accounted for most of the flight hours during the Deep Freeze 62 season, but the detachment also flew some 40 hours of general support in the McMurdo area and at Hallett Station. At the latter, in 1 1/2 hours, the two UH—lBs, using external slings, transported 30,000 pounds of cargo from the icebreaker Eastwind to Hallett Station—an excellent example of the speed and efficiency of ship-toshore- operations using helicopters.

Topo East and West

Encouraged by the success of Topo North and South, two new surveys—Topo East and West— were planned for the 1963-1964 summer season, to complement the work of the previous year. Topo West would extend the area covered by Topo North some 300 miles west from Cape Adare to Davies Bay; Topo East would run from the Beardmore Glacier, where Topo South had ended, to the Horlick Mountains. During the off-season, the two UH—lBs used in Deep Freeze 62 were refitted with higher performance engines and a third helicopter was added to the project. In October 1963, the detachment arrived at McMurdo aboard two Air Force C-124s

Engine change in —20° F. temperature at 10,500 feet altitude on Mount Discovery. U.S. Navy Photo.

On October 29, the two UH—113s selected to support Topo West (the third was held as a backup at McMurdo) departed for Hallett Station, a distance of 395 miles, but were forced to return to McMurdo because of deteriorating weather conditions. Three days later, they tried again and, after 3 hours and 55 minutes of flight, arrived safely at Hallett. Poor weather delayed the start of the survey until November 4, and while the weather remained generally marginal, the survey was completed in 25 days, only 9 of which were flyable. During this period, UH—113s spent some 85 hours in the air and enabled the USGS engineers to establish control over an area of approximately 45,000 square miles. The helicopters returned to McMurdo on November 29.

On December 19, all three UH—lBs flew from McMurdo to Beardmore Station on the Ross Ice Shelf, a small summer weather installation located at the foot of the Beardmore Glacier. The weather was good, and Topo East was begun the following day. As on Topo West, only two UH—lBs were used for the actual survey operations, the third being given the mission of helping Navy aircraft to move camp equipment and place fuel caches.

The two surveys covered approximately the same amount of area in approximately the same time. It had originally been proposed to extend Topo East as far as the Whitmore and Thiel Mountains, but when the Ohio Range of the Horlick Mountains was reached, the survey team found that to continue would involve flying under poor weather and light conditions. The project was therefore terminated on January 20 after another 40,000 square miles had been surveyed and a sufficient number of geodetic control points established to permit the construction of accurate maps.

While still engaged in the survey operations, one of the UH—lBs had flown from the base camp at Bartlett Glacier to the vicinity of Mount Weaver, where a team of geologists was carrying on investigations. The one day that the helicopter was able to assist in this project proved so fruitful that it was agreed that the entire detachment would return upon completion of the survey project. It did so on January 23. The subsequent operations around Mt. Weaver stirred further the enthusiasm of the geologists, who reported that they had accomplished in three days what would have taken at least as many months using ground transportation.2 This success also established a precedent for future Army helicopter operations in the Antarctic.

Above, a hero shot of the Army helicopter crews up on the old garage roof, in front of the orange striped bamboo flagpole. From left: kneeling, SP/5 Paul George, 1st Lt. Charles Beaman, Capt. Neal E. Early, CWO John P. D'Angelo, and SP/5 Louis J. Harrison. Standing: SP/5 James C. McCaslin, Captain Frank H. Radspinner, Jr., S/Sgt Robert X. Anderson, CWO Joe R. Griffin, and SP/5 Frank L. MacPherson. U.S. Navy Photo.

Flight to the Pole

At Mount Weaver, the Army Aviation Detachment found itself far closer to the South Pole than to McMurdo Sound, and it seemed reasonable to fly to the Pole to await pick-up by Navy LC—130 aircraft. It would be a historic flight, and the Army fliers at Mount Weaver checked and rechecked their flight planning for 13 days while waiting impatiently for a break in the weather.

Finally, in the afternoon of February 4, after receiving the go-ahead from flight control at McMurdo, the UH—lBs, heavily loaded with fuel, started for the Pole. Flying at 12,000 feet under the watchful eye of an LC—130F acting as a search and rescue aircraft, the trip was relatively smooth and uneventful. Two hours and 24 minutes after takeoff, the trio of helicopters arrived safely, becoming the first, and thus far the only, rotary-wing aircraft to reach the South Pole.

When initially conceived in 1961, the Army helicopter support was not planned to be a continuing program. But, by Deep Freeze 64, the Iroquois had become so integral a Part of the Navy's Support operations that the Army agreed to continue the mission of the detachment. Consequently, the unit was given a more permanent status and redesignated as the 62nd Transportation Detachment (Medium Helicopter) (Provisional).

As a result of the previous year's success around Mt. Weaver, the detachment was given the task of supporting geological field work during Deep Freeze 64. Operations were scheduled for the Hallett Station area and in the Sentinel Range of the Ellsworth Mountains.

The weather, as it had many times before in Antarctica, defeated well-laid plans when two UH—lBs were damaged beyond repair by a storm the day they arrived at Hallett Station, forcing the cancellation of investigations in that area. The damaged helicopters were returned to the United States for repair but, to insure completion of the second part of the schedule, the Army provided two new aircraft which arrived at McMurdo early in December.

With three UH—lBs available, the remainder of the operations proceeded as planned. The helicopters were loaded into 1C—130Fs and flown to Camp Gould in the Sentinel Mountains. This first use of the LC—130F to place the UH—1B at a remote field site emphasized the remarkable flexibility of both aircraft. The technique was to be used many times over the following years with continued success. From mid-December to early February, the UH—lBs flew some 300 hours in support of the Sentinel Mountains investigations. permitting the geologists to accomplish about five times the work that would have been possible with ground transportation, and in fact, much of it in areas accessible by no other means.

For the geologists, it was a rewarding experience. Freed from the requirement to travel by ground transportation, they could inspect escarpments, summits, and inaccessible rock outcrops, and collect a large volume of samples for further study without undue regard for their weight.

The work begun in earlier seasons continued in Deep Freeze 65. During October and November, 1964, the Army Aviation helicopters again supported U. S. Geological Survey topographic engineers. Ground-control points were established in the David Glacier area, completing the Topo North operations of 1961-1962, and in the Hallett area, extending the Topo West survey. The detachment devoted the remainder of the tune to supporting geological teams, first in northern Victoria Land, carrying out the program that had been cancelled the year before. It then moved to the Shackleton Glacier area, and finally to the western Horlick Mountains. The pilots logged twice as many flight hours (over 650) as in the previous season.

Scene of the first UH—1B helicopter crash in Antarctica. U.S. Navy Photo

Unfortunately, these accomplishments were marred by the first U14—IB flight accident. On November 8, 1964, while landing a geological party, a helicopter crashed just below the summit of a 13,800-foot peak in the Admiralty Range, Victoria Land. The helicopter was damaged beyond repair, but luckily no one was injured. The crash was attributed to lack of sufficient power for landing control at that altitude. Another factor that may have contributed to the accident was the lack of sufficient oxygen, which may have caused a mild case of hypoxia in the crew.

In addition to the limitations of the UH—1B which contributed to the crash, another severe restraint was the short cruising range of the helicopter. One attempted remedy was the installation of internal and external auxiliary fuel tanks. They proved unsatisfactory, however, because they greatly reduced the useful payload of the aircraft, especially when flying at higher altitudes.

Multidiscipline Research

Over the years, the UH—lBs had demonstrated their ability to support more than one kind of research activity. It was not until Deep Freeze 66, however, that projects in different sciences operating in the same geographical area were combined into a single program in order to take full advantage of the helicopters' versatility. This program, known as the Pensacola Mountains Survey, was the most coinprehesive survey ever planned for a remote part of the Continent.3

To support the Pensacola Survey, a base camp called Camp Neptune was established by Navy aircraft, at 83°30'S. 57°00'W., and the UH—lBs were brought in by LC—130F. The Army detachment flew over 500 hours in support of various programs—priniarily topographic control, geology, and gravimetry. The success of the project established the feasibility of using the turbine helicopter for such mnultidiscipline work and encouraged planning of further combined programs.

For the Army detachment it was a good year— accident free and with few maintenance problems. Prior to the start of the season, the unit had been redesignated as the U.S. Army Aviation Detachment (Antarctica Support) , a name it was to retain through the rest of its career. The personnel complement was set at six officers and six enlisted men, while the number of aircraft remained at three. A new external fuel tank system had been devided for the helicopters that increased their flight time by 1 1/2 hours. In practice, however, the tanks caused excessive vibration whenever the aircraft attained speeds of 75 knots and above, and the pilots firmly believed that the increased range was not worth the possible damage to the airframes. Thus, the problem of increasing the range remained unresolved

UH—18 helicopter on display at the U.S. Army Transportation Museum. U.S. Army Transportation Museuum Photo.

Marie Byrd Land Survey

Following up the success of the Pensacola Project, a major helicopter-supported field operation—the Marie Byrd Land Survey—was begun in Deep Freeze 67. The survey, a multidiscipline exploration of the Marie Byrd Land coastal area, involved 18 scientists and engineers who made geological, biological, topographic, geophysical, and paleomagnetic observations over a three-month period from early November to late January.' To support this operation, the Army Aviation Detachment deployed with three new UH—IDs. This helicopter, with much improved perform- ance characteristics over the UH—1B (see table), promised to be a much more versatile aircraft. Taking advantage of the aircraft's increased range, the UH—lDs were flown the 700 miles to the field camp established in the Ford Ranges. An LC—130F refueled the helicopters on the surface at Roosevelt Island and provided navigational assistance during the flight.

From the start, the Marie Byrd Land Survey was plagued with bad weather and, although the marginal weather of the area had been considered in preseason planning, delays were longer than expected. To compound the difficulty, a UH—1D fell victim to whiteout conditions and blowing snow' on November 5, and crashed while trying to evacuate a field party that had been stranded for two days on a mountaintop. Although the crew sustained only minor injuries, the aircraft was lost and could not be replaced until over a month later.

To make the limited flying time as useful as possible, fuel caches were placed east and west of the main camp and, by taking maximum advantage of breaks in the weather, the detachment was able to fly 400 hours of the scheduled 600. The first year of the Marie Byrd Land Survey was another test of the capabilities of the UH—11D, and the Army crews were pleased with the aircraft's performance.

The Army helicopters continued their support of the Marie Byrd Land Survey during Deep Freeze 68. This time, however, instead of ferrying the helicopters to the field campsite, they were loaded into LC—130Fs at Christchurch and airlifted to the field site, with cnly a fuel stop at McMurdo, to minimize loading and unloading damage. As expected, the poor weather again limited flight operations, but the available flight time was made more productive by limiting the radius of operation to 150 miles. Three campsites were occupied and 372 hours were flown, compared to the planned 5 campsites and 470 flight hours.

Operations in Ellsworth Land

In the 1968-1969 season, the survey was extended eastward into Ellsworth Land. The Army helicopters were again flown from Christchurch to the field site by way of McMurdo. From October 24, 1968 to January 30, 1969, the UH—lDs flew 314 hours in support of the science program, using the techniques developed during the preceding two years. This was the last deployment for the detachment. Upon its return to the United States, the unit was deactivated and its helicopters transferred to the Navy, who will fly them for the support missions beginning with Deep Freeze 70.

Conclusion

Any assessment of the impressive record of the U.S. Army Aviation Detachment (Antarctica Support) can only conclude that the introduction of the turbine helicopter to Antarctica was a technological innovation of major consequence. It allowed scientists to carry out investigations in a fraction of the time that would have been required with other means of transport, and enabled them to reach locations that crevasses and other natural obstacles would otherwise have rendered inaccessible. Although of limited range, the helicopter's altitude capability made possible investigations in the rugged mountains of West Antarctica.

Technical data

| UN-lB | UN-lD | |

|---|---|---|

| Rotor span | 53' | 48' |

| Height | 13'2" | 14' 5 1/2" |

| Length | 38'3" | 44'10" |

| Power plant | Lycoming gas turbine | Lycoming gas turbine |

| Gross weight | 6,600 lbs. | 9,500 lbs. |

| Average payload | 2,115 lbs. | 2,900 lbs. |

| Passengers | 5 - 8 | 5 - 8 |

| Fuel consumption | 60 gals/hour | 75 gals/hour |

| Fuel capacity | 165 gals | 220 gals |

| Maximum speed | 120 mph | 120 mph |

| Crew | 2 | 2 |

| Average range | 200 miles | 360 miles |

U.S. Army helicopter operations in Antarctica, 1961-1969

| Season | Number of personnel assigned | Number of helicopters | Detachment commander | Major activities supported | Hours flown | Operational areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Freeze 62 | 10 | 2 UH—1B | Lt. J. H. Green | Topo North and South | 240 | Beardmore Glacie north to Cape Adare |

| Deep Freeze 63 | 10 | 3 UH—1B | Capt. F. H. Radspinne | Topo East and West; Geological field work | 216 | Northern Victoria Glacier to Horlick Mountains; Geographic South Pole |

| Deep Freeze 64 | 14 | 3 UH—1B | Maj. P. M. Cagle | Geological field work; Geodetic control | 304 | Sentinel Range; Ellsworth Mountains |

| Deep Freeze 65 | 12 | 3 UH—1B | Maj. W. C. Hampton | Geological field work; Geodetic control | 659 | McMurdo; Hallett; David Glacier; Shackleton Glacier; Horlick Mountains |

| Deep Freeze 66 | 12 | 3 UH—1B | Maj. W. C. Hampton | Pensacola Mountains Project: Geological field work | 536 | Pensacola Mountains; McMurdo |

| Deep Freeze 67 | 13 | 3 UH—1D | Maj. B. R. Hawkins | Marie Byrd Land Survey | 403 | Marie Byrd Land |

| Deep Freeze 68 | 13 | 3 UH—1D | Maj. B. E. Luck, Jr. | Marie Byrd Land Survey II | 372 | Marie Byrd Land |

| Deep Freeze 69 | 13 | 3 UH—1D | Maj. B. E. Luck, Jr. | Ellsworth Land Survey | 314 | Ellsworth Land |

Notes

1. For a map of the area covered by Topo North, South, East, and West and a detailed discussion of topographical survey techniques used, see Antarctic Journal, vol. I, no. 2, pp. 40-50.

2. The impact of the turbine helicopter on the research program was discussed by George A. Doumani in the Antarctic Journal, vol. I, no. 6, p. 255-264; and by Robert H. Rutford and Philip M. Smith in the Polar Record, vol. XIII, no. 84, p. 299-303.

3. See Antarctic Journal, vol. I, no. 4, p. 123-124.

4. See Antarctic Journal, vol. II, no. 4, p. 92-97.

The history behind a rare orange U.S. Army helicopter with ties to the South Pole and Fort Eustis

by Myles Henderson

This UH-1B helicopter, tail number 61-788, was one of three U.S. Army helicopters to make the first rotary wing flight to the geographic South Pole.

FORT EUSTIS, Va. — I recently visited the U.S. Army Transportation Museum to check out a piece of military history with a local connection.

When you hear the words “army transportation”, you probably picture jeeps, tanks, or aircraft painted dark green. So why is this Huey helicopter orange?

"The Army does that when it's not expected to be a combat vehicle," says Matthew Fraas, Education Specialists at the U.S. Army Transportation Museum. "If they're using it for testing, or for some other kind of experiment, they will paint it orange. That way, the enemy knows it's not a combat thing. But more importantly, if something goes wrong, during that testing, bright orange will stand out quite clearly against any kind of backdrop."

In February of 1963, this helicopter was one of three to make the first rotary wing flight to the geographic South Pole.

"The Army does things other than train for war or fight in wars. A lot of times, they participate in various experiments, or even in some cases, scientific expeditions." says Fraas.

It was part of Operation Deep Freeze and even though the mission took place over 8,000 miles away, it does have a local connection.

"We actually had a whole military command that was devoted to supporting the Army's activities at the north and the south poles, Army Arctic Command was based here at Fort Eustis."