MacArthur’s small ships: Improvising Water Transport in the Southwest Pacific Area

BY Kenneth J. Babcock

American History No. 90 (Winter 2014)

Title Image (Composite): 46 foot motor tow launches in wet storage at the Los Angeles Port of Embarkation awaiting assignment to Pacific theaters/National Archives

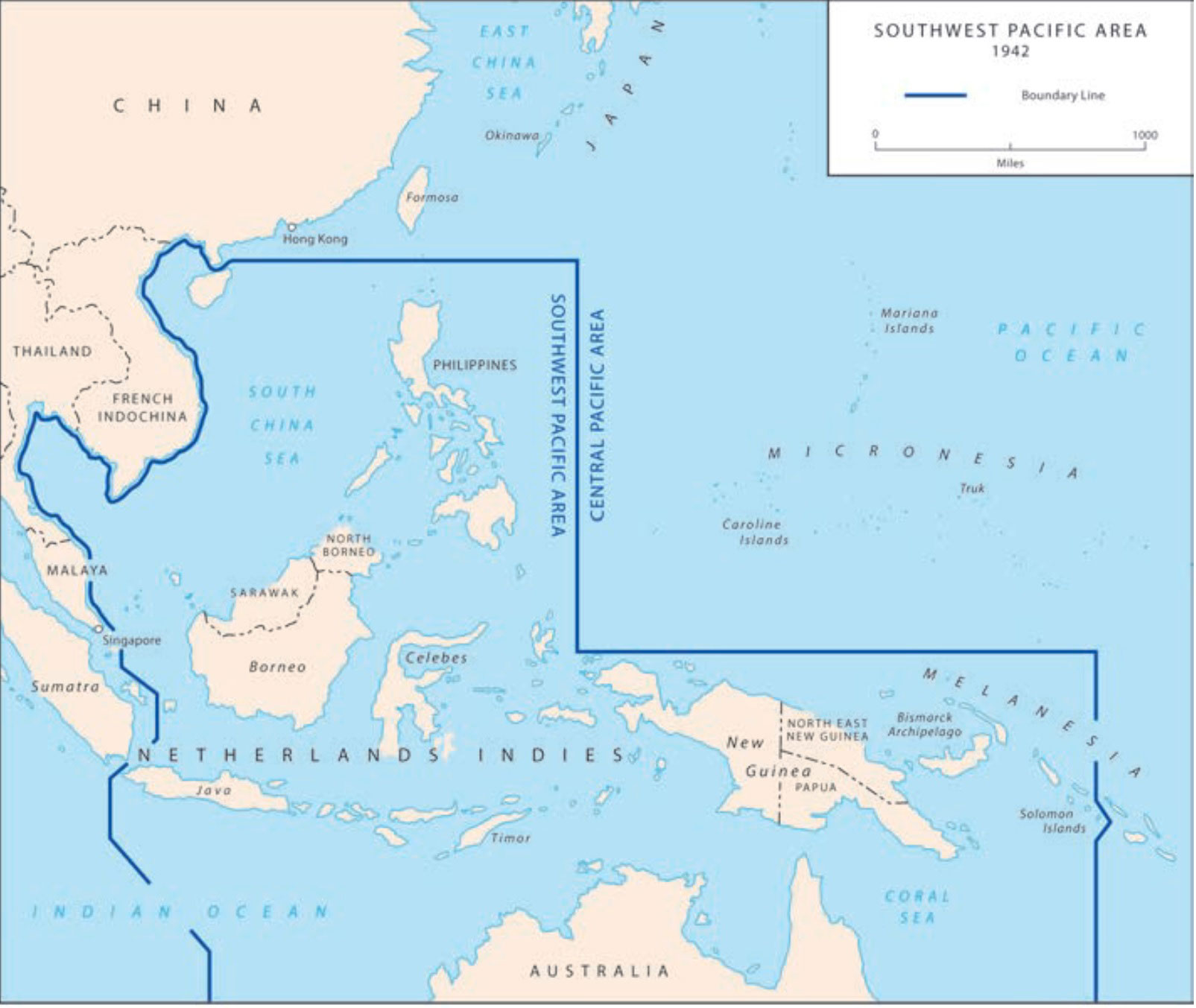

Water transportation was crucial to the United States Army’s success against Japan in the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) during the Second World War. Here, the U.S. Army faced some of the most complicated sustainment problems encountered during the war. Transport distances were long and resources scarce throughout the region. On the front lines, Allied forces faced an enemy entrenched throughout a complex region of rugged islands and atolls. Further complicating matters, strategic planners estimated that there were not enough available resources from the United States to support offensive operations in the SWPA until the middle of 1943.

Despite these challenges, General Douglas MacArthur was not content to remain in a defensive posture for long when he assumed command of the General Headquarters (GHQ), SWPA on 18 April 1942. He and his logisticians operated in a military environment that stressed urgency and economy of force over other considerations. Innovation and improvisation in transportation and supply operations were crucial to MacArthur’s early transition to of fensive operations. In fact, historian Martin Van Creveld argues that the Allies in the European Theater of Operations (ETO) achieved their victory partially due to “their disregard for the preconceived logistics plans as to their implementation.”1 In this regard, the SWPA was no different. The formation and employment of the U.S. Army Small Ships and deployment of the U.S. Army’s 2d Engineer Special Brigade (ESB) illustrates the benefits of innovation and improvisation during MacArthur’s New Guinea Campaign and beyond.

The SWPA Operational Environment

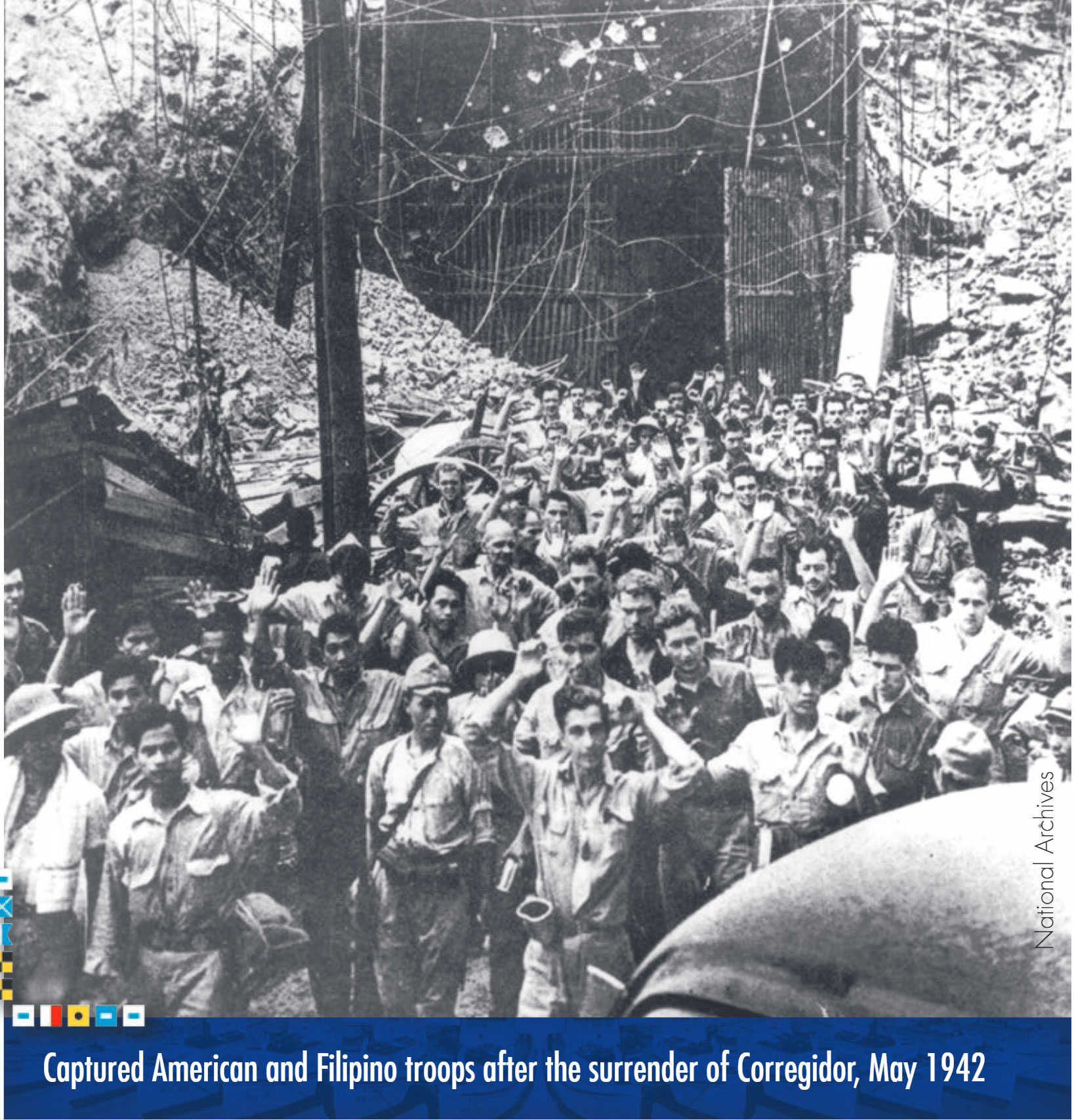

The United States faced complex challenges in worldwide strategic and operational sustainment as it undertook one of the largest military operations in history. These were the direct result of a two-ocean war. Further, Japan’s surprise attack against Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 completely disrupted America’s existing deployment and sustainment plan for the Pacific theater during the first seven months of the war. The Army quickly realized that “virtually every previously planned movement of forces had to be modified or abandoned.”2 This included service troops, equipment, and supplies. Sustainment challenges in the Pacific were further complicated by American strategic policy designating Europe as the decisive theater and the priority for support. Under this policy, the United States accepted greater risk over Far East interests by assuming that a citadel defense of strategic forward bases was sufficient to contain Japanese offensives until the crisis in Europe stabilized. However, Japan’s rapid advance quickly threatened lines of communications between the U.S. west coast and Allied possessions in the Pacific. Japan captured Guam and Wake Island before the end of 1941 and applied tremendous pressure on Captured American and Filipino troops after the surrender of Corregidor, May 1942

National Archives Image

U.S. forces in the Philippines, forcing their surrender in May 1942. When MacArthur assumed command of the SWPA, the Japanese southern limit of advance stretched along a 3,000-mile-long front from Java to the Solomon Islands. Allied resistance on Papua New Guinea had prevented Japanese forces from advancing on the Australian mainland. Allied forces were successful in stalling Japanese advances in New Guinea through the ll-but-impenetrable Owen Stanley Mountains. On the south coast, the Australians maintained a strategic base at Port Moresby, which became the Allied primary defensive anchor in New Guinea. The Kokoda Trail was the best avenue of approach across the Owen Stanley Mountains. Japan’s only other feasible option was to attack Port Moresby by sea. Japanese military leaders needed all of New Guinea in order to secure Japan’s southern defensive line and open up the eastern Australian coast line for possible invasion. Early in the war, Japan launched three failed invasions toward Port Moresby. These first resulted in a failed overland invasion from Dutch New Guinea, second in the Battle of the Coral Sea, and finally in a failed counteroffensive during General MacArthur’s Papua Campaign along the Owen Stanley Mountains and the Buna-Gona region. These battles illustrate the brutal challenges of ground and ad-hoc amphibious warfare in the Southwest Pacific.

Map of the Southwest Pacific Area of control which borders the Ceneral Pacific Area of Command.

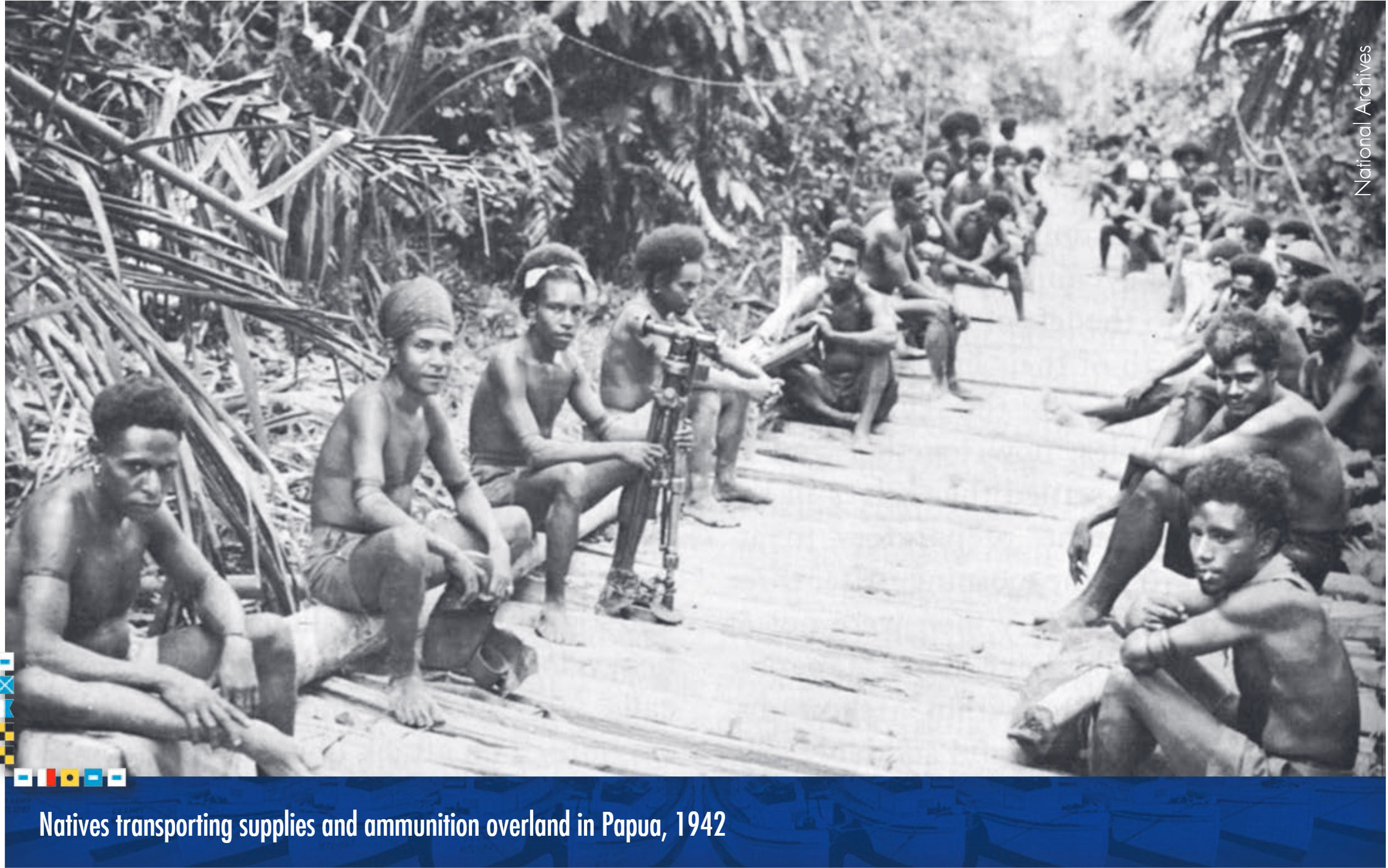

The geography and harsh environment of forward combat areas severely tested sustainment operations in the SWPA. The first problem was transporting men, equipment, and supplies from the United States to Australia to shore up and sustain theater defenses. Supply routes between the United States and Australia represented the longest lines of communications throughout the war. This “created a heavy strain” on available American shipping within the Pacific.3 Even within the SWPA itself, intra-theater shipping faced the prospect of operating in an area greater than the size of the continental United States. Transit distances between Australian ports and Port Moresby exceeded the length of the eastern coastline of the United States. The tactical distribution of supplies around New Guinea was also a daunting task. Resupply by sea, with some augmentation by aircraft, was the only practical method of supporting combat operations. Both Allied and Japanese armies quickly learned that effective ground resupply between Port Moresby and Buna over the Kokoda Trail was impracticable.4 Combat troops, even with the aid of local natives, could only pack a fraction of the supplies needed for any ground offensive over the Owen Stanley Mountains. At sea, coastal pproaches to most SWPA islands, including New Guinea, were treacherous. Coral reefs and sandbars dominated much of these shorelines. To compound matters, military navigation charts of the area were outdated or incomplete and deepwater ports in the combat zone were scarce.

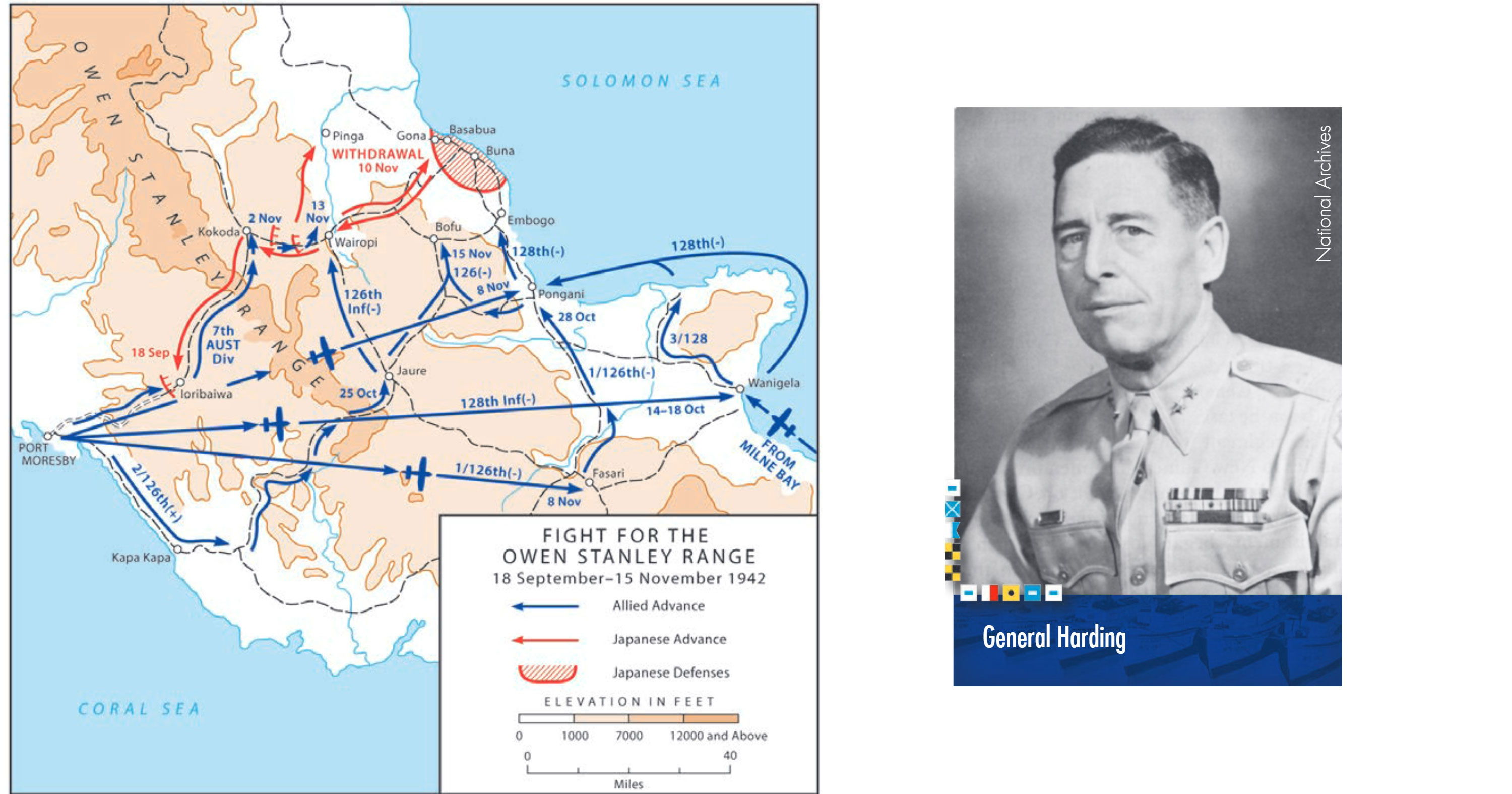

Map of New Guinea in 1942

National Archives Image.

The second problem facing Allied forces in the SWPA, and one of the most pressing, was a shortage of intra-theater transport. General MacArthur’s plan relied on a rapid rate of advance along the northern shore of New Guinea. During a staff meeting, he remarked that “island-hopping. . . with extravagant losses and slow progress is not my idea of how to end the war as soon and as cheaply as possible.”5 However, his forces were still subject to two common principles of warfare. First, an army’s rate of advance is a direct function of available days of supply. At one point during the Papua Campaign, Maj. Gen. Edwin F. Harding, commander of the 32d Infantry Division, reported that his slow advance during the Buna assault was directly related to chronic shortages of basic supplies. General MacArthur apparently did not accept this explanation and relieved Harding in the middle of the campaign. Regard less, MacArthur’s forces could only advance as fast as the supply situation permitted. Second, an army’s direction of advance is a function of its lines of communications. Allied forces in the SWPA required water transports capable of moving troops, equipment, and supplies in the U.S. Army’s direction of advance along the northern coast of New Guinea. Throughout the Papua Campaign, the Allies operated on a “logistical shoestring” that depended on Australian resources and innovative ways to maximize economy of force in operational planning.6 Fortunately, the U.S. Army was in the process of establishing local water transport capabilities to support both rate and direction of advance for the New Guinea Campaign. This gave MacArthur’s forces freedom of maneuver during the first two years of the war despite a shortage of transportation assets from the United States.

(left) Map of Fight for the Owen Stanely Range (right) General Edwin F. Harding, U.S. A. Photo from National Archives.

UJ.S. Army Water Transportation in the SWPA

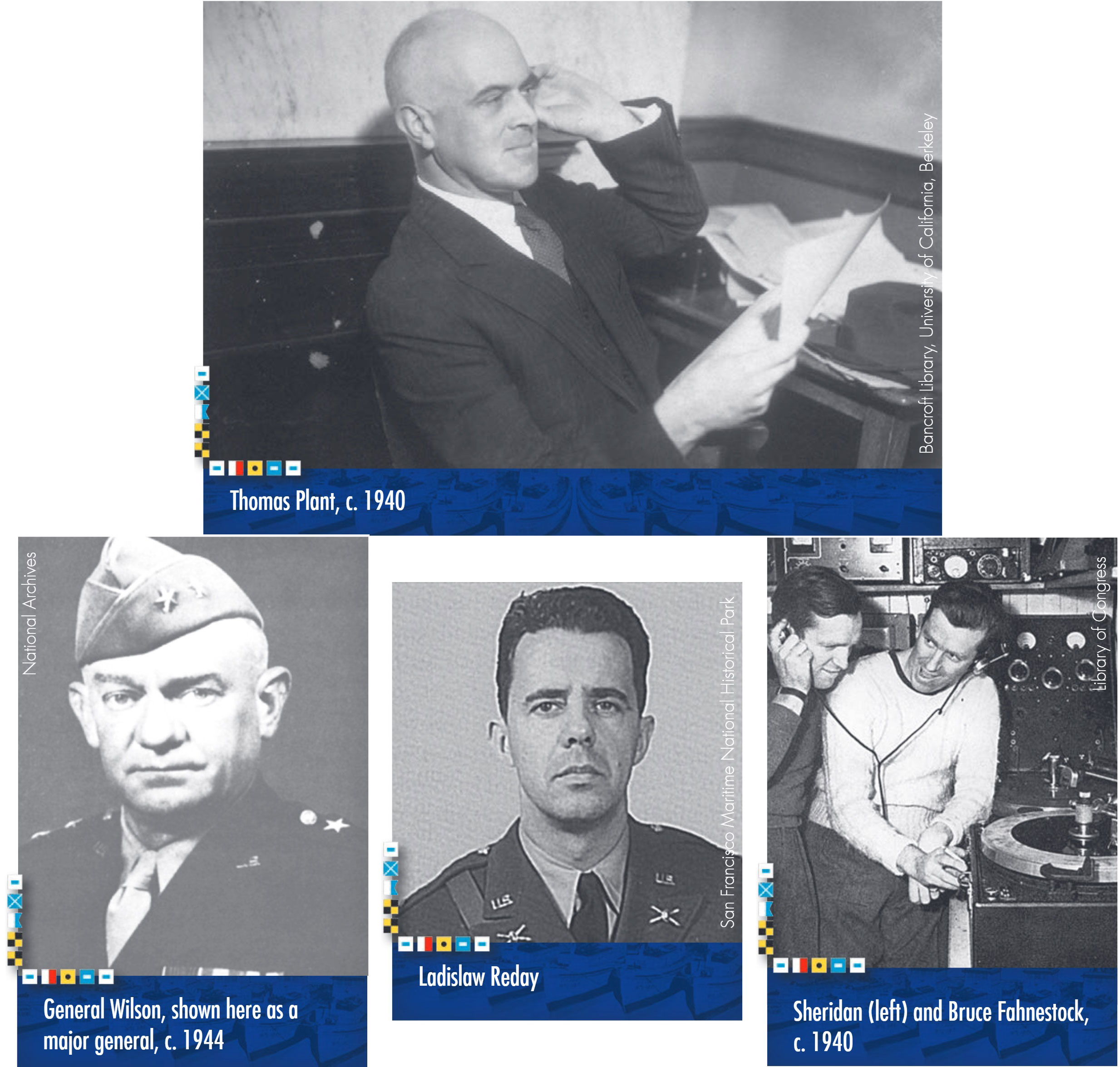

In early 1942, the United States dispatched a group of experienced American transportation executives to Australia to establish the Army Transportation Office. Brig. Gen. Arthur R. Wilson, who was appointed the Chief Quartermaster and Assistant Chief of Staff, G–4, U.S. forces in Australia on 21 March, recruited many of these professionals for their commercial expertise. Col. Thomas G. Plant was the first U.S. Army officer assigned over the Water Section of the Transportation Division. He was a businessman who at one time had served as the vice president of the American Hawaiian Steamship Line.7 He brought with him a small team of “trained shipping men” capable of managing strategic ocean cargo operations. In April 1942, the Transportation Division reported that Colonel Plant’s team included “a staff of approximately nine experienced Water Transportation men with an additional seven to come.” The Army expanded this section to fifty officers, twenty soldiers, and forty-four civilians by the end of the year.8 The Army selected men with similar skills to plan and direct complex large ship operations throughout the SWPA. Concurrently, another group of specialists established a sister organization to manage a fleet of small local watercraft until American industrial production of amphibious and cargo ships caught up with demand.

(top) Image of Thomas Plant (left) General Wilson, shown here as as major general c. 1944 (center) Ladislaw Reday (right) Sheridon(left within image) and Bruse Fahnestock c. 1940, Photo from Library of Congress.

Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, American explorers John Sheridan Fahnestock and Adam Bruce Fahnestock proposed the idea of organizing a fleet of small vessels to infiltrate relief supplies to MacArthur’s forces in Bataan. The Fahnestock brothers were experienced adventurers with six to eight years sailing the South Pacific and were familiar with the New Guinea coastline. They skippered a Grand Banks fishing schooner named Director II in the years before the Second World War. Their crew included Dawson “Gubby” Glover,Ladislaw Reday Ladislaw Reday San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park Phil Farley, Bob Wilson, and Ladislaw “Laddie” Reday. Their unorthodox plan caught the attention of General Arthur Wilson.9 With his endorsement, senior Army officials accepted the Fahnestocks’ proposal. The Army commissioned Sheridan as a captain, his brother Bruce as a first lieutenant, and the next three crewmen as second lieutenants. Laddie Reday had already earned an Army commission by this point. Over time, the Fahnestocks recruited two other members of their family from Australia, including brother-in-law Sgt. Heath Steele and cousin Sgt. Frank Sheridan. Future colleagues affectionately referred to these men as “the Originals.” In March 1942, the Army dispatched this group to Australia.10

>The Director II, 1943 State Library of Queensland.

The Army designated the Fahnestock relief mission to Bataan the “Mission X” expedition. These men arrived in Melbourne by air where they received news that Bataan had fallen.11 Realizing there was still an immediate need for small watercraft, General Wilson placed the Mission X team under the command of Col. Harry Cullins with instructions to establish the Small Ships Supply Command directly under U.S. Army forces in Australian control.12, 13 This was no small feat for Colonel Cullins. The Originals had quickly developed a reputation as men who regularly ignored military discipline and decorum. According to Australian employee John B. “Jack” Savage,14 the Army recalled Colonel Cullins out of retirement specifically to “instruct the group in the ways of the Army. At times he despaired.”15 A few months later, Maj. George P. Bradford replaced Colonel Cullins. Major Bradford was also a former steamship executive having served as president of the Everett Steamship Company in Manila before the war.

On 29 May 1942, the Water Branch of the Army Transportation Office in Australia assumed operational control of the group, and on 14 July 1942, formally announced the formation of the U.S. Army Small Ships Section. The unit headquarters occupied a portion of the Grace Hotel in Sidney, Australia, from 1942 to early 1947.16 As the war progressed, the section assumed a greater role in managing intra-theater lift using small vessels. The author of an anonymous memorandum released on 15 December 1942 predicted that “sooner or later, small water craft of a wide range of types would be indispensible as the island campaign gained momentum.”17

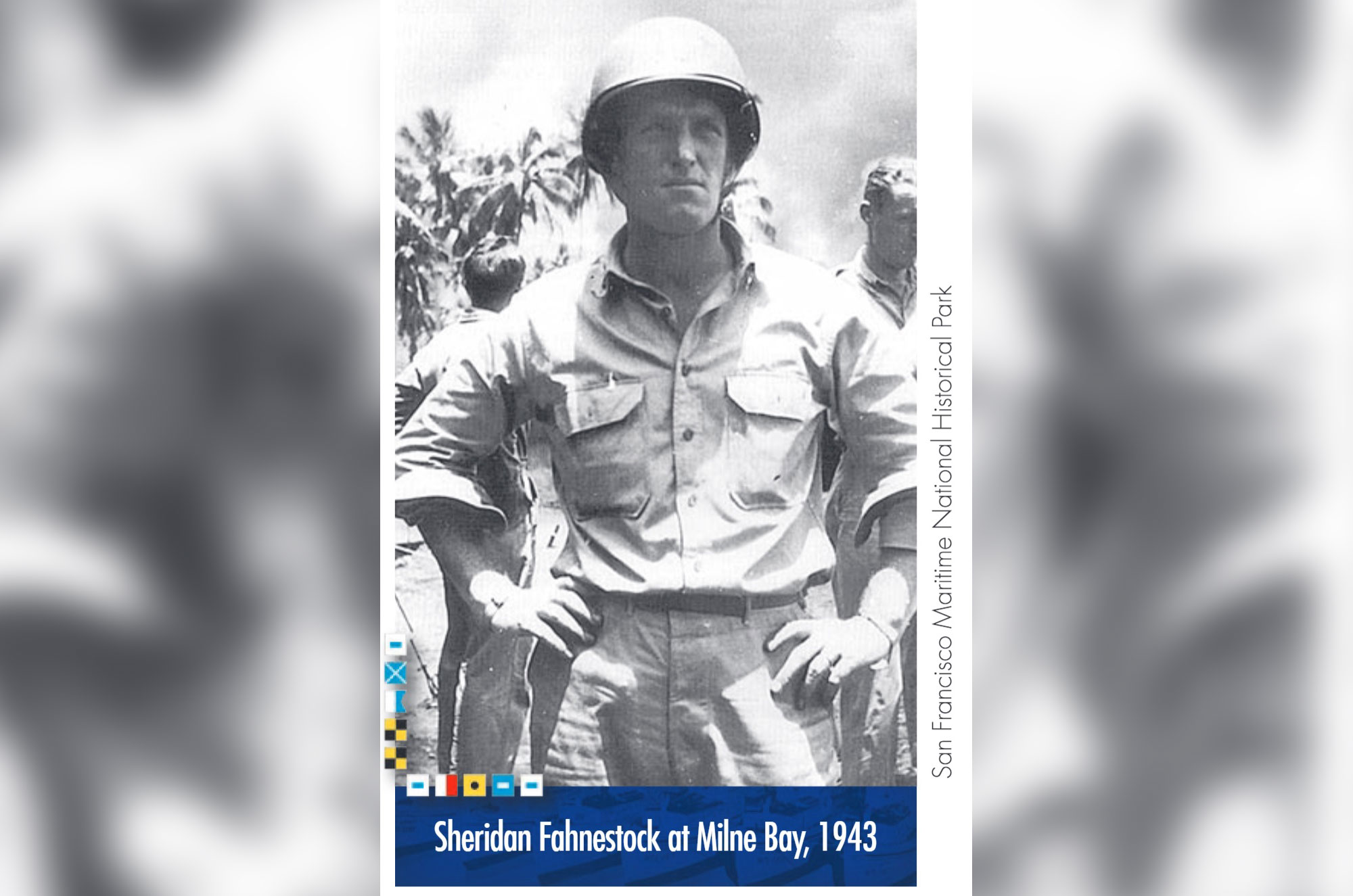

Sheridan Fahnestock at Milne Bay, San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park.

The U.S. Small Ships took an inventive approach to assemble a fleet of small watercraft capable of operating in the shallow coastal waters of New Guinea. According to Jack Savage, the section first established the administrative organization “needed to handle the acquisition of a fleet of small craft; to carry out the conversions, recruit crews, and attend to provisioning of these ships.”18 With the arrival of With the arrival of Major Bradford and additional experienced ship managers on 15 June 1942, Captain Fahnestock and the Originals were free to travel throughout the region to procure small commercial vessels suitable for military use.19

A month later, the Transportation Service formally assigned the U.S. Small Ships a unique mission that included assembling and operating coastal vessels, the responsibility to “man, equip, provision, repair, and maintain” the small boat fleet, and authority to coordinate small boat operations with larger U.S. Army–operated vessels. On 12 January 1943, the U.S. Small Ships assumed additional responsibility for small boat construction and tactical employment.20 This task included the authority to directly hire local carpenters, mechanics, shipwrights, and laborers to operate certain boat repair facilities in northern Australia subject to ongoing Japanese air raids.21 The U.S. Small Ships hired these men under an exception to local Army policy. Typically, the U.S. Army arranged Australian-provided services through local labor unions. Under these circumstances, they did not hire union laborers due to strict union rules relating to hostile fire areas. Hiring nonunion laborers allowed the Army to continue to operate northern ports subjected to regular enemy attack.

The Will Watch from New Zealand was typical of small sailing vessels employed by the Small Ships Section. San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park.

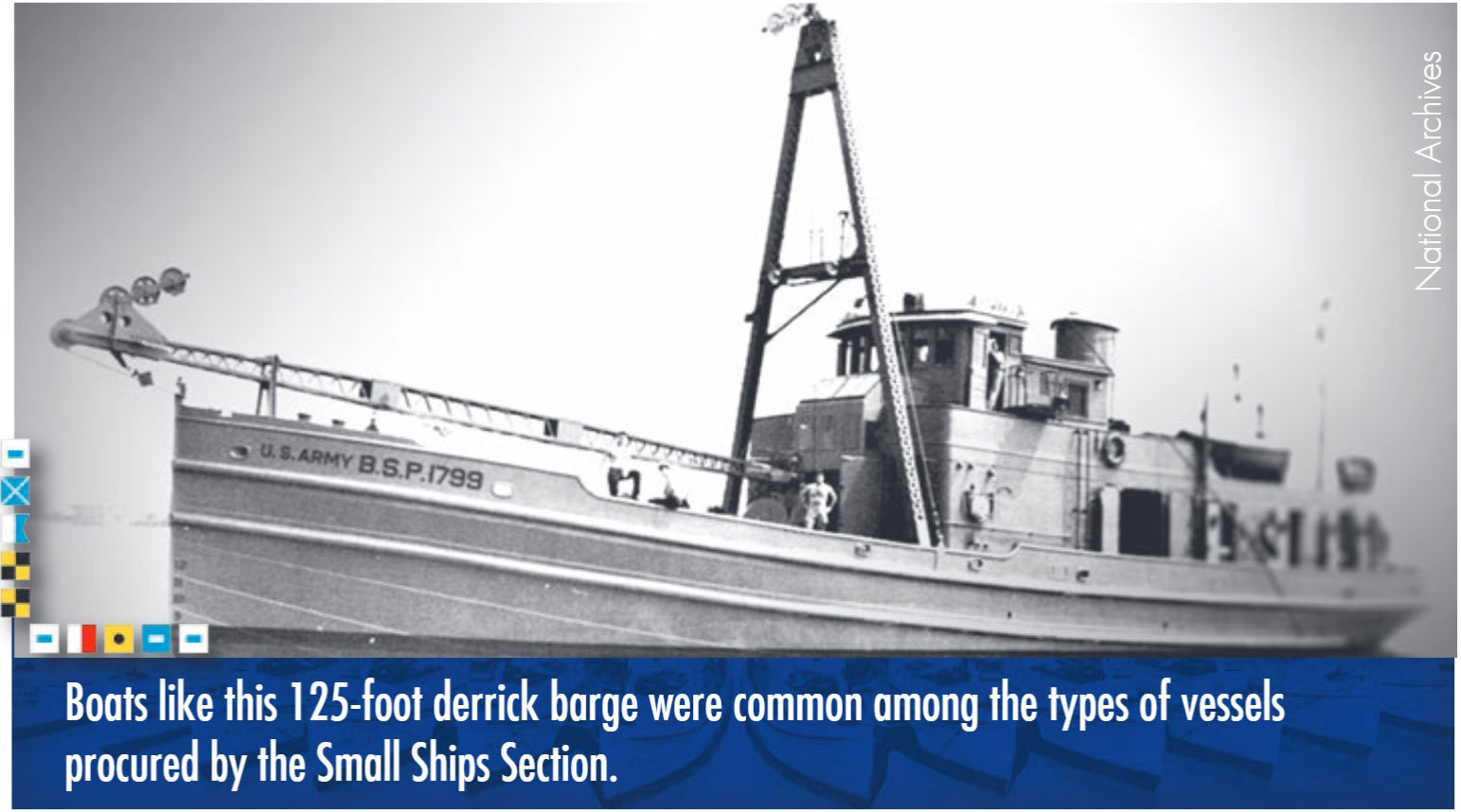

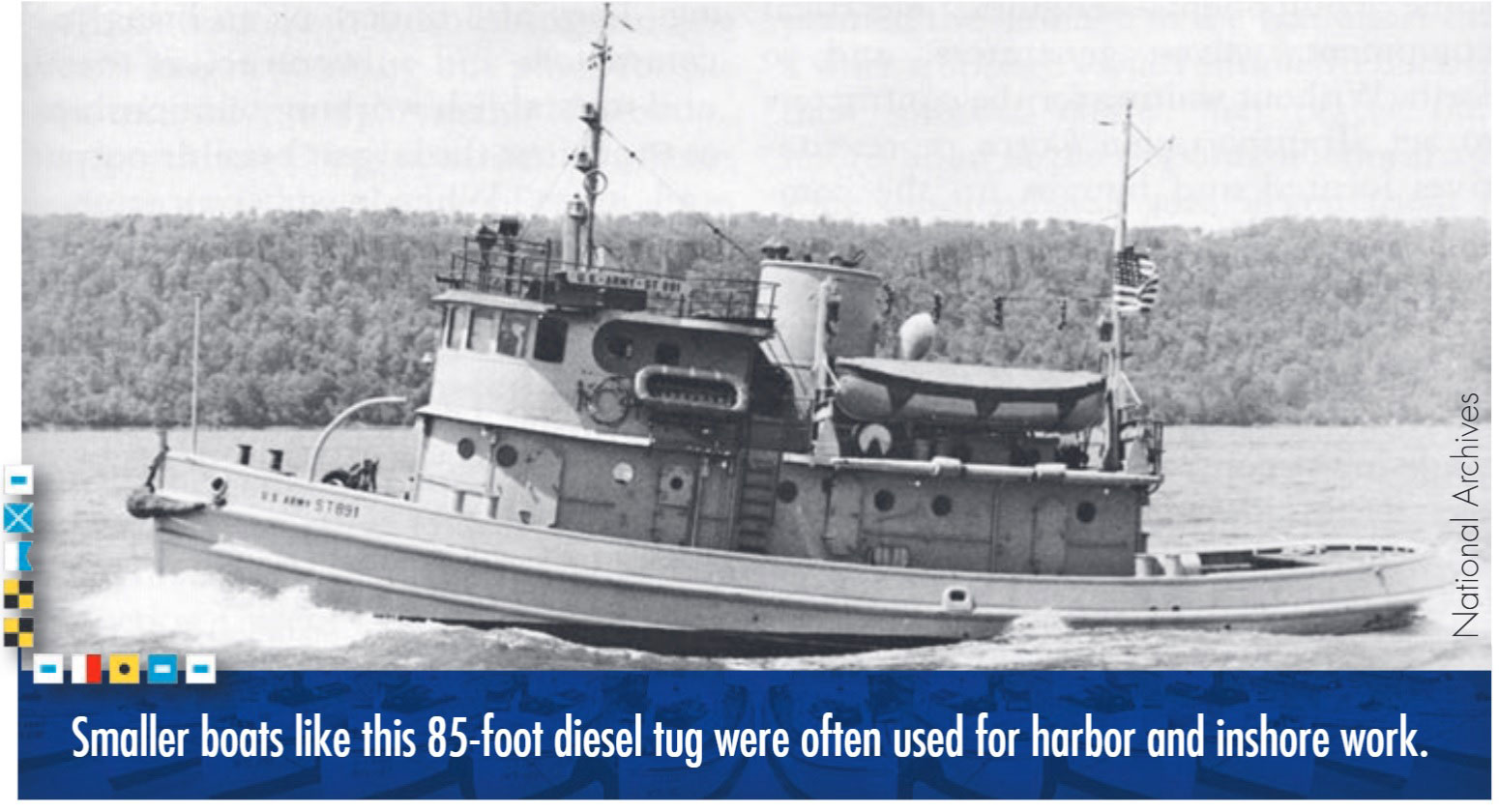

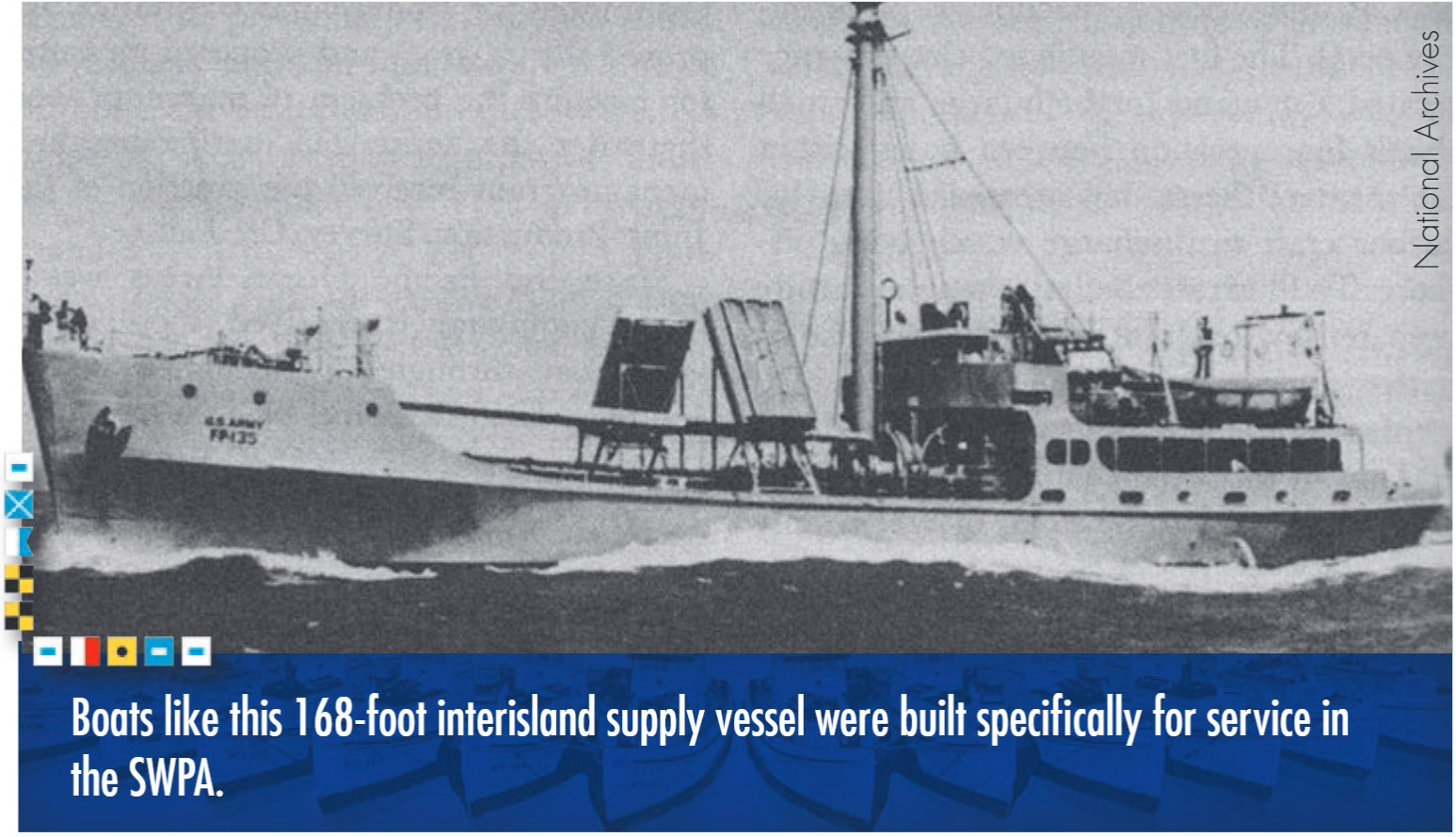

The U.S. Small Ships took advantage of provisions in the American lend-lease program with Australia to acquire a variety of local commercial sailing vessels for U.S. military use. Lend-lease had greatly benefited America’s European allies, and the Army was determined to adapt this innovative program to the SWPA as well. Additionally, Australian naval officers assisted the U.S. Small Ships in purchasing vessels using credits accumulated under reverse lend-lease funds.22 Occasionally, Captain Fahnestock’s team was even able to procure vessels registered in other countries, including New Zealand and the Netherlands. The U.S. Small Ships focused mainly on commercial boats operating along the coasts of Australia and New Zealand. The Australian government granted authority to the U.S. Army to lease, purchase, or commandeer any private boat deemed suitable for wartime service. The U.S. Small Ships purchased a number of fishing trawlers, sailing sloops or ketches, plywood landing craft, and even obtained a few larger steel freighters operating in Australian territorial waters. They quickly learned that fishing trawlers were useful for amphibious operations due to a winch capable of pulling the vessel back out to sea. They also discovered that ketches were useful for transport and lighterage operations over shallow reefs and break tides. Larger vessels in the fleet included several commandeered Dutch freighters and a World War I destroyer converted into a commercial transport.23 By 1943, the Army began placing orders with Australian shipyards for new wooden and steel barges, ocean lighters, and steel tugs.24

Photo from the National Archives

The men of the U.S. Small Ships understood the urgency of their task and most times negotiated a purchase or settlement with each boat owner on the spot. According to Australian employee Norm Oddy, “the haste of the whole business was astonishing. It had to be. The Japanese were getting closer to Australia each day. There was no time for extended haggling.” In each case, once the Americans procured a ship, “the Australian flag was taken down and the Stars and Stripes was raised.” With ownership papers in hand at the conclusion of each purchase, the U.S. Small Ships then opened negotiations with the crew. It should also be noted that according to maritime law, many of these vessels were not technically American since they remained registered in Great Britain or other nations. (Australia did not maintain a distinct ship registry at the time.) The U.S. Army never formally registered vessels under U.S. authority. As a result, some Australian veterans who served as crew on these vessels argue that they technically did not operate foreign vessels during the war.25

Photo from the National Archives.

The U.S. Army used a practical and innovative approach to man the vessels of the U.S. Small Ships fleet. After concluding their business with the owners, the U.S. Small Ships offered contracts to the existing crews of each vessel at the time of purchase. “No longer having a boat to work with,” most crews agreed to employment with the Army.26 The host government also authorized the U.S. Army to hire local civilians who otherwise did not qualify for Australian military service. Typical crews included men too old, too young, or medically unable to meet Australian military standards. This was the most expedient way to hire experienced crews in light of shortages of Army technical service personnel in the SWPA. Typically, the U.S. Army offered each crewman a six-month contract extendable to twelve months for satisfactory service. Interestingly, these contracts could only be entered into or renewed while on Australian soil. This restriction did not deter many from seeking extended service with the U.S. Small Ships throughout the war.

Photo from the National Archives.

The Army’s newly acquired small watercraft performed a variety of amphibious, supply, medical evacuation, and reconnaissance missions through out the New Guinea Campaigns and beyond. The U.S. Army exclusively managed this small watercraft fleet since the U.S. Navy did not provide amphibious vessels to the SWPA until 1943. The Army’s fleet was not originally designed for these missions, yet the fleet proved its effectiveness in many atypical roles. For example, in preparing for Allied landings at Buna in October 1942, a flotilla from the U.S. Small Ships shuttled rations and ammunition along with Army Quartermaster and Ordnance teams from Port Moresby to the staging area at Wanigela. An account of the 107th Quartermaster Detachment records that the commander of the 32d Division’s coastal task force then requested immediate transport for two companies of combat troops to Pongani. The division quartermaster, Lt. Col. Laurence McKinney, assigned two trawlers to transport “about a hundred men of the 128th Infantry” forward. These vessels were able to navigate “treacherous and uncharted reefs around Cape Nelson, with the aid of native guides stationed at the bows to spot the reefs.”27 As the campaign progressed, the U.S. Small Ships fleet also evacuated Allied wounded and Japanese prisoners on return trips. Control of the U.S. Small Ships fleet was largely decentralized in order to allow these small vessels to move supplies based on local needs.

The U.S. Small Ships were crucial to Allied efforts to defend New Guinea and Australia early in the war. Army vessels ferried a large portion of military supplies to Port Moresby and Milne Bay, while the Allied armies defended against Japanese incursions across the Owen Stanley Mountains. Facing chronic shortages on the battlefield, these ships delivered enough supplies to keep the Allied armies operational. Many vessels of the U.S. Small Ships operated freely along the coast despite the constant threat of air and sea attack. During a Japanese amphibious assault on 25–26 August 1942 against Ahioma on the north shore of Milne Bay, two ketches attempted to extract an Australian infantry company assigned to defend the area. One of the ketches sailed directly into a Japanese amphibious assault wave and was sunk. The other boat returned to Ahioma and the soldiers ultimately marched out of the area.28Although enemy action disrupted this particular operation, the Allies recognized the benefits of similar tactics using the U.S. Army’s small boats to move soldiers along the coast.

Photo from the National Archives.

After the battle over Milne Bay, the U.S. Small Ships were able to undertake larger resupply missions. Dutch freighters Anshun and Bantam docked at Gili Gili on 6 September 1942, one day after the Japanese withdrawal. However, the Anshun capsized that evening after two departing Japanese warships attacked. The Anshun remained in place on its side as a breakwater at the port for about a year before the Allies refloated and towed it back to Australia for repairs.29 This incident did not deter the Allied armies from launching the first of many amphibious landings in New Guinea the following month using the vessels of the U.S. Small Ships employing nontraditional methods. Allied forces conducted their first landing on New Guinea on the morning of 18 October 1942 using ships never designed for amphibious operations. A group of 102 soldiers disembarked from two fishing trawlers thirty miles south of Buna at Pongani. The U.S. Small Ships continued to support amphibious landings, while R. Adm. Daniel Barbey, the Seventh Amphibious Force commander, was building and training General MacArthur’s main amphibious forces in Australia. The U.S. Small Ships also received additional support from Australian forces.

Photo from the National Archives.

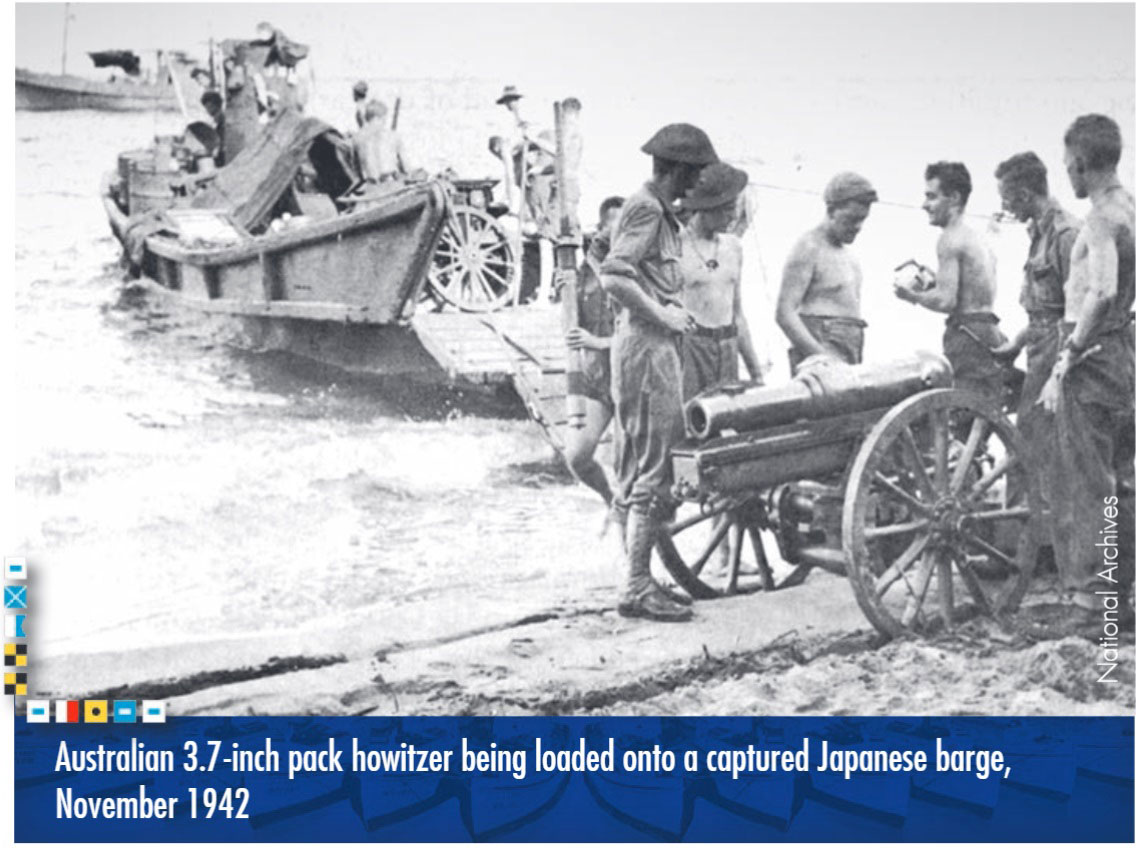

On 28 October 1942, the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) attached a small team of military volunteers from the 2/7th Battalion, AIF 6th Division, to augment the U.S. Small Ships. The original twenty members of the 2/7th Battalion attached to the U.S. Army were also no strangers to improvisation during their six-month assignment. According to Australian veteran Harold W. Hopperton, these troops operated eight small marine plywood landing barges known as Higgins Boats. The Army gave the team just one day to learn how to operate their boats before dispatching them to Oro Bay. Upon their arrival, these men worked to recover another Dutch freighter, the Van Heutsz, which the Japanese recently attacked and sank in thirty feet of water. “Using our Higgins Boats we unloaded all the gear on the deck. Then with Captain Collins and his heavy helmet and other diving equipment, and by using one of our barges as a pumping platform, we brought up everything salvageable below the water. Of course we man aged to bring up a case of beer with each dive!”30 Weeks later, Australia expanded this small team with fifteen more soldiers to crew two additional boats. The U.S. Army assigned these men to transport amphibious forces as well as ammunition and rations during the Allied transition to offensive operations. This bridged a significant capabilities gap for Allied forces until MacArthur’s Seventh Amphibious Force received enough American combat landing craft in 1943 to continue the campaign.

The Two Freddies (background) under tow near New Guinea, c. 1942. San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park.

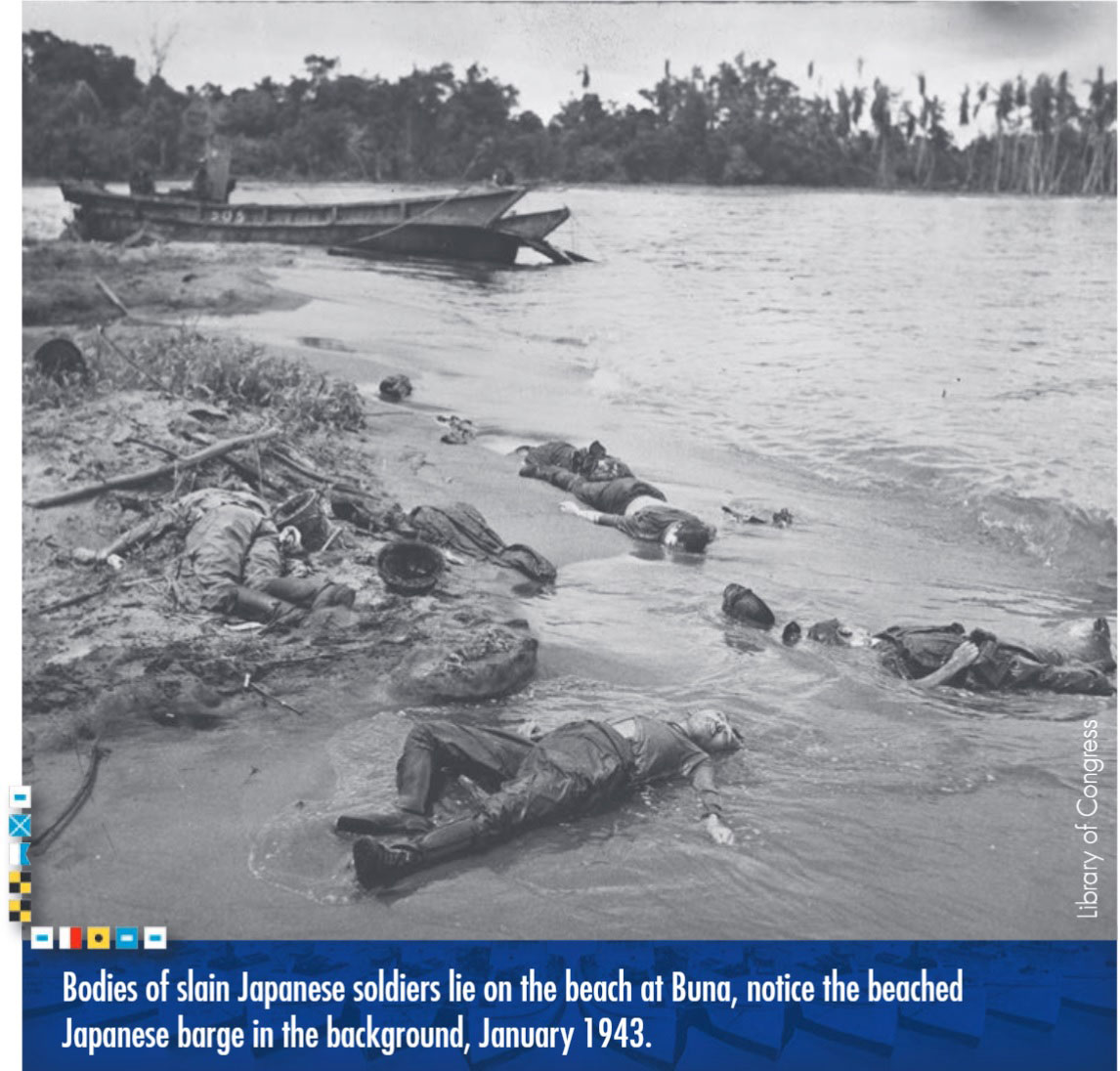

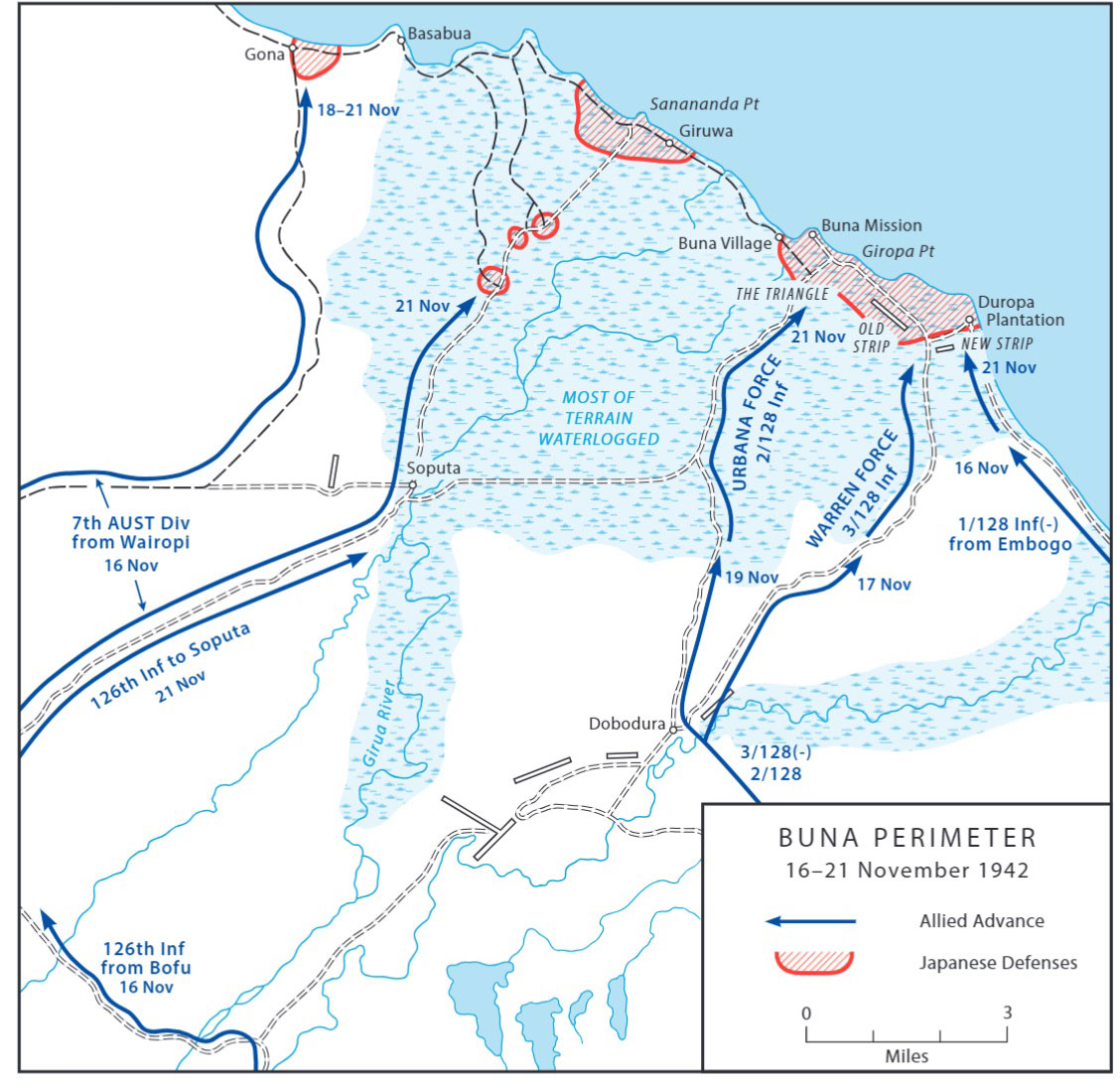

Japanese attacks against Allied small coastal vessels also had a detrimental effect at times on tactical operations along the north coast of New Guinea. Even though the Army had the foresight to arm its small vessel fleet with machine guns, Japanese air attacks were still effective. The events of 16–17 November 1942 demonstrate how enemy interdiction against the U.S. Small Ships sometimes created significant problems for ground operations. On the evening of 16 November, eighteen Japanese Zero fighter planes attacked a small group of vessels unloading rations, ammunition, and weapons within the vicinity of Oro Bay. Each boat was equipped with either a .50-caliber or .30-caliber machine gun, but these did little to deter the enemy planes. During the attack, Japanese planes sunk the lugsail boats Alacrity, Bonwin, and Minnemura, and a cap tured Japanese barge, along with all of their cargo. The division commander, General Harding, was a passenger on the Minnemura but survived the at tack. Col. Laurence McKenney, the 32d Division’s chief quartermaster, however, perished in this attack. His replacement, Maj. Ralph Birkness, immediately requested airdrops of supplies to replace a crucial portion of the high-value cargo that had been lost.31

Subsequent Japanese air raids against the U.S. Small Ships on 17 November resulted in the beaching of the Willyama and severe damage to the Two Freddies. The Kelton was the only lugsail boat that survived this encounter without damage. Concerned with his immediate supply situation, General Harding ordered the 128th Infantry under command of Brig. Gen. Hanford MacNider to delay a planned advance against Buna until the Army could replace some of the lost supplies.32 For the most part, the 32d Division’s offensive against Buna stalled at this point. Author Bill Lunney argues that, in retrospect, General Harding overstated the shortage of available shipping in the area. “There was (as he must have known) an increasing number of Small Ships arriving in Milne Bay.” He cites evidence that several other boats transported a group of Australian mountain howitzers to Oro Bay over the following weeks.33 Regardless, MacArthur replaced Harding in late November as a result of the 32d Division’s stalled advance. Both the U.S. Army Services of Supply and the Army Air Forces (AAF) were able to mitigate this supply crisis by December 1942 when the Dobodura and Popondetta airstrips became operational. Further, additional boats arrived in the area under improved air coverage designed to protect coastal lines of communications. The U.S. Small Ships also increased night operations to avoid enemy air attack.

Photo from the National Archives.

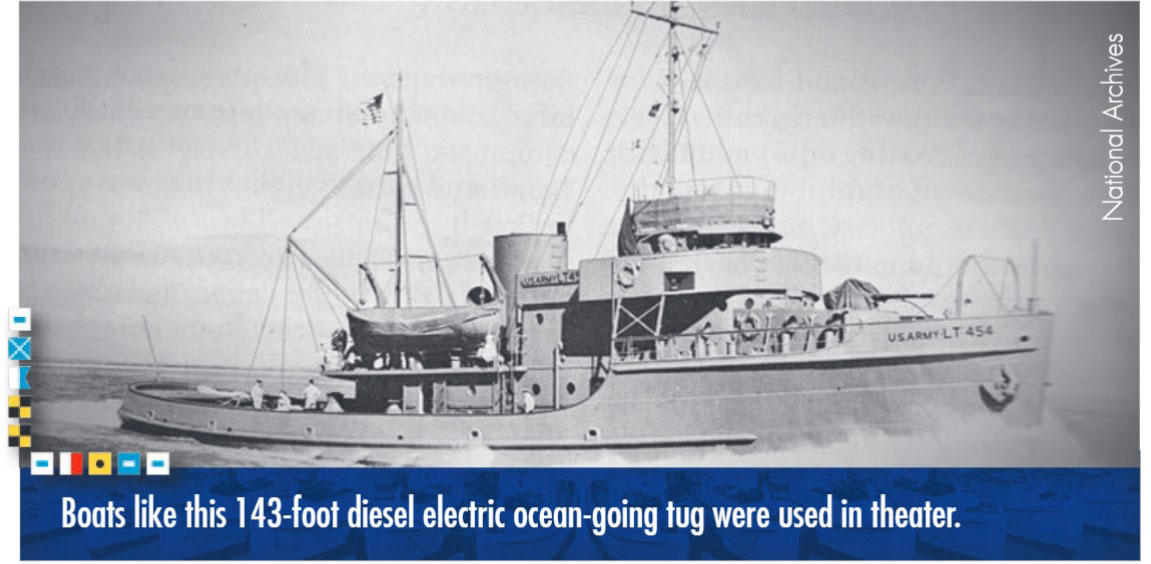

In 1943, the U.S. Army Small Ships Section continued to provide much-needed support for MacArthur’s forces in forward locations. As the Allied ground and amphibious forces pushed up the coast of New Guinea, sailors also noticed a larger presence of warships, invasion barges, and aircraft. A steady buildup of Allied resources slowly overtook that of the enemy. Fleets of both small and large transport vessels increased in size, while Army Air Forces and Navy forces continued to interdict Japanese shipping. “Many new Small Ships were now being built in Australia,” including tugboats, which were an important addition to the fleet due to their flexibility. These boats could “tow barges laden with rations, ammunition, petrol,” or other items to forward storage depots while retrograding empty barges for reloading. Tugs presented an advantage since “ships had to wait to be loaded or discharged; tugs didn’t.”34 This was an innovative way to efficiently transport supplies throughout an area that lacked a robust network of docks.

Photo from the Library of Congress.

Strategic supply routes from the United States also slowly improved. At one point, the Army procured small commercial vessels in the United States for use in the Pacific. These included a fleet of coastal cargo ships called “lakers,” so named because of their previous service in North American Great Lakes. The first laker, City of Fort Worth, arrived in Australia on 12 March 1943. Nineteen other vessels eventually followed although one sank en route. Many of these vessels had already endured twenty years of service and required expensive reconditioning and constant upkeep for continued military service. Regardless, “the theater could not have done without them.”35 In all, a total 469 domestic and foreign vessels served in the U.S. Small Ships fleet throughout the war.36 A growing number of larger vessels of various types also supported the war effort in the SWPA as they became available.

Map of Buna Perimeter 16-21 November 1942.

Australian civilians served on the crews of some of the larger U.S. flagged amphibious and supply vessels under control of the Water Transport Division of the Army Transportation Service (ATS). These civilian sailors mitigated shortages of replacement crewmen on U.S. cargo vessels dedicated to the SWPA. David Everett, an Australian veteran of the U.S. Small Ships, signed up with the ATS after fulfilling his U.S. Small Ships contract as a teenager. The ATS assigned him as a crewman on the American laker Camorada to replace a U.S. crewman returning home. According to Everett, local sailors commonly replaced “those that left and went back to the states” before new crews arrived. “They banded with Australians such as myself and a lot of other nationalities,” including Norwegian and English. Everett also saw service on other lakers, including the West Texas, Colorado, and Atlantic Trader. He recalls, “there were about seven or eight of them running; came out here with American crews and replaced them with whatever was available, mainly Australians.”37 U.S. Small Ships sailors also lent a hand on the Army’s freight supply craft known as the FSs. Both Army and Coast Guard crews operated these vessels, but many U.S. crewmen were inexperienced. Australian veteran Bernie O’Brian sailed on the FS–285 as second officer. He recalls that he had “to teach these GIs how to steer. They’re all farmers from Tennessee, South Carolina, Alabama, and so on. . . . I taught them other things as time progressed [including knots and] how to use a [boatswains chair] without killing yourself and so on.”38 Even Admiral Barbey commented on the inexperience of his amphibious ship crewmen. He observed that “if the LSTs [Landing Ship, Tank] had green crews, the LCIs [Landing Craft, Infantry] had even greener ones.” He marveled at how a small cadre of experienced sailors chaperoned “so much inexperience across the seas to far-away Australia.”39 As a combined force, the Allies were able to overcome many challenges at sea and along the shore through improvisation and clever innovation.

Photo from the National Archives.

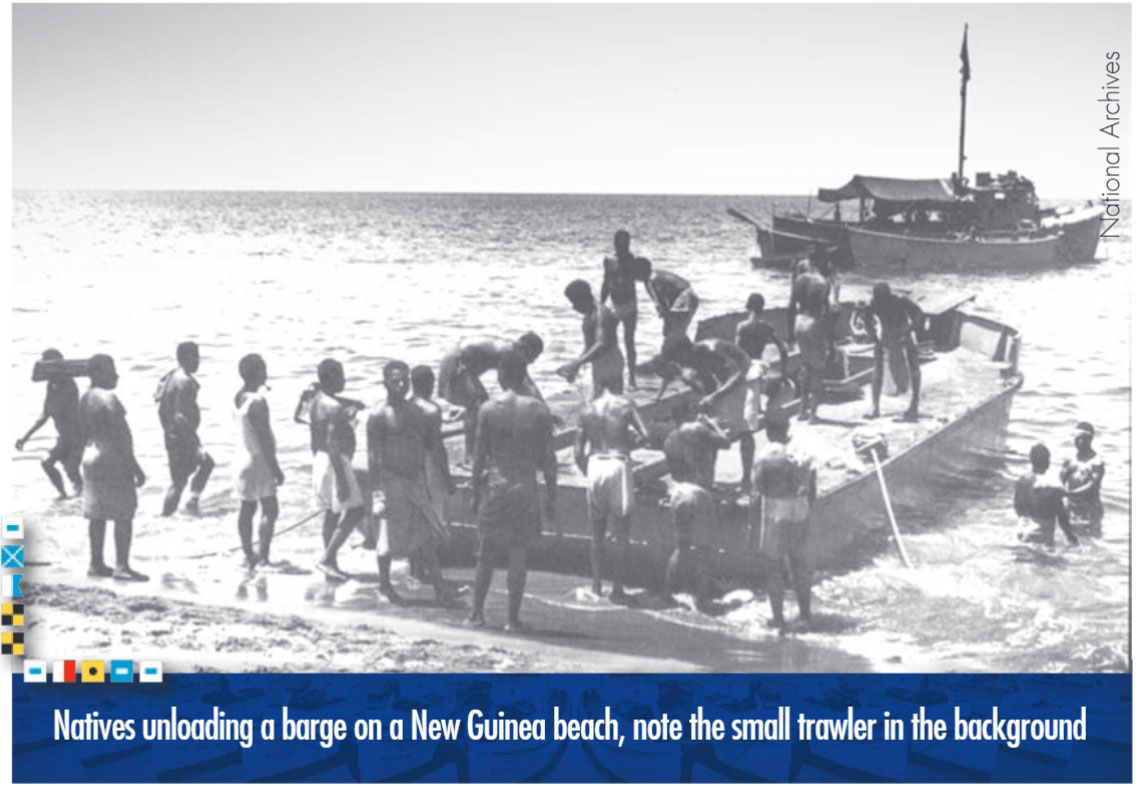

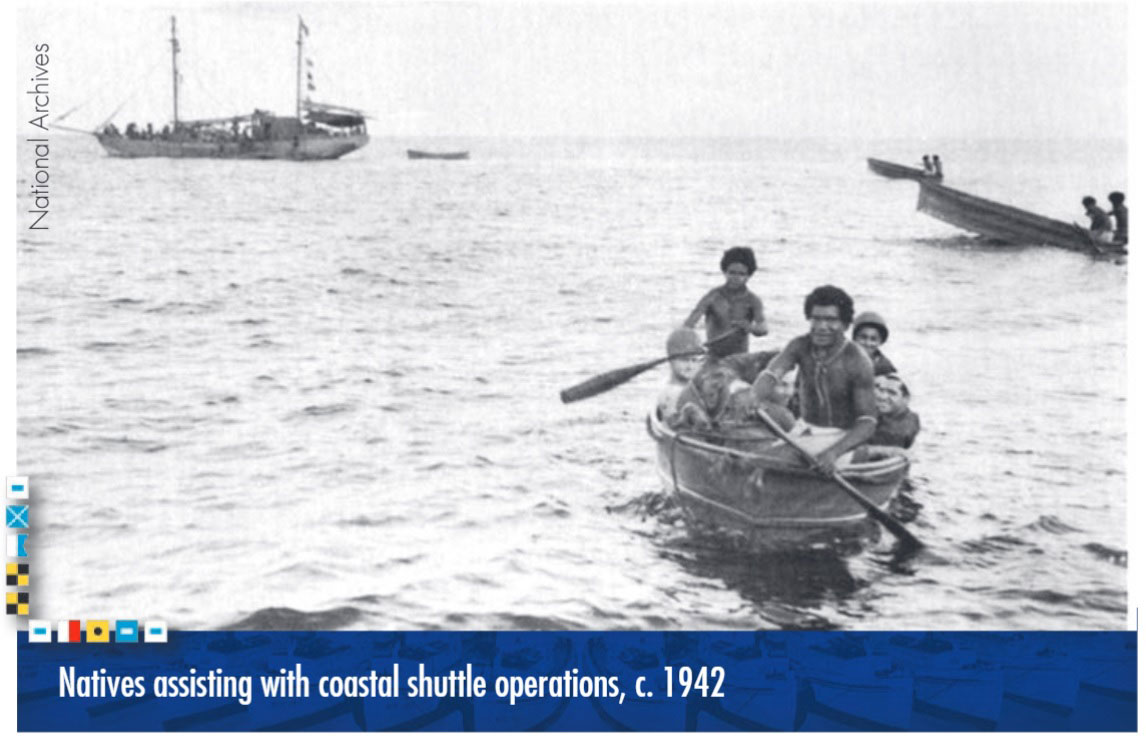

SWPA forces mitigated acute shortages of service personnel at forward tactical ports and amphibious landing sites by relying on local nationals, Army engineers, and even combat soldiers to offload U.S. Army watercraft in forward areas. Many of these personnel shortages resulted from a lack of strategic troop transports. This created a “backlog of 40,000 service troops earmarked for the SWPA, and MacArthur preferred that combat troops receive priority” movement.40 Locals often filled technical service shortages out of necessity. Their use in forward secure areas was somewhat unorthodox, yet effective. U.S. Army watercraft often discharged cargo at night onto barges and auxiliary craft, which were then “manhandled through the surf and onto the beaches.”41 Along the New Guinea coast, the native population performed an invaluable service in discharging supplies onto amphibious landing sites. Known as Fuzzy Wuzzies, these natives at times even swam supplies from a boat directly onto shore. Bernard Smith, an Australian veteran of the U.S. Small Ships, recalls how a team of New Guinea natives did just this. He remarked, “They were terrific. We’d take heads of 44 gallons of aviation fuel, and they’d take these drums and they’d push them and swim with them up in the tide. They had done their bloody job well.”42

Photo from the National Archives.

Combat soldiers also provided much-needed labor at times to discharge supplies. However, this did little to boost morale. For many, “one of the most common, and hated, jobs that combat soldiers in the Pacific theater performed was unloading supply ships, usually in brutal heat and humidity.”43 In 1943, Lewis Lapham, the civilian executive assistant to the general in command of the San Francisco Port of Embarkation, remarked that “commanders who would not permit their combat troops to handle cargo were exhibiting ‘short-sighted stupidity.’ Only the 41st Division has recognized the necessity of putting soldiers to work as stevedores.”44 Army engineers also supported shore party activities, along with traditional engineer missions, to keep supplies running through the shoreline.

Photo from the National Archives.

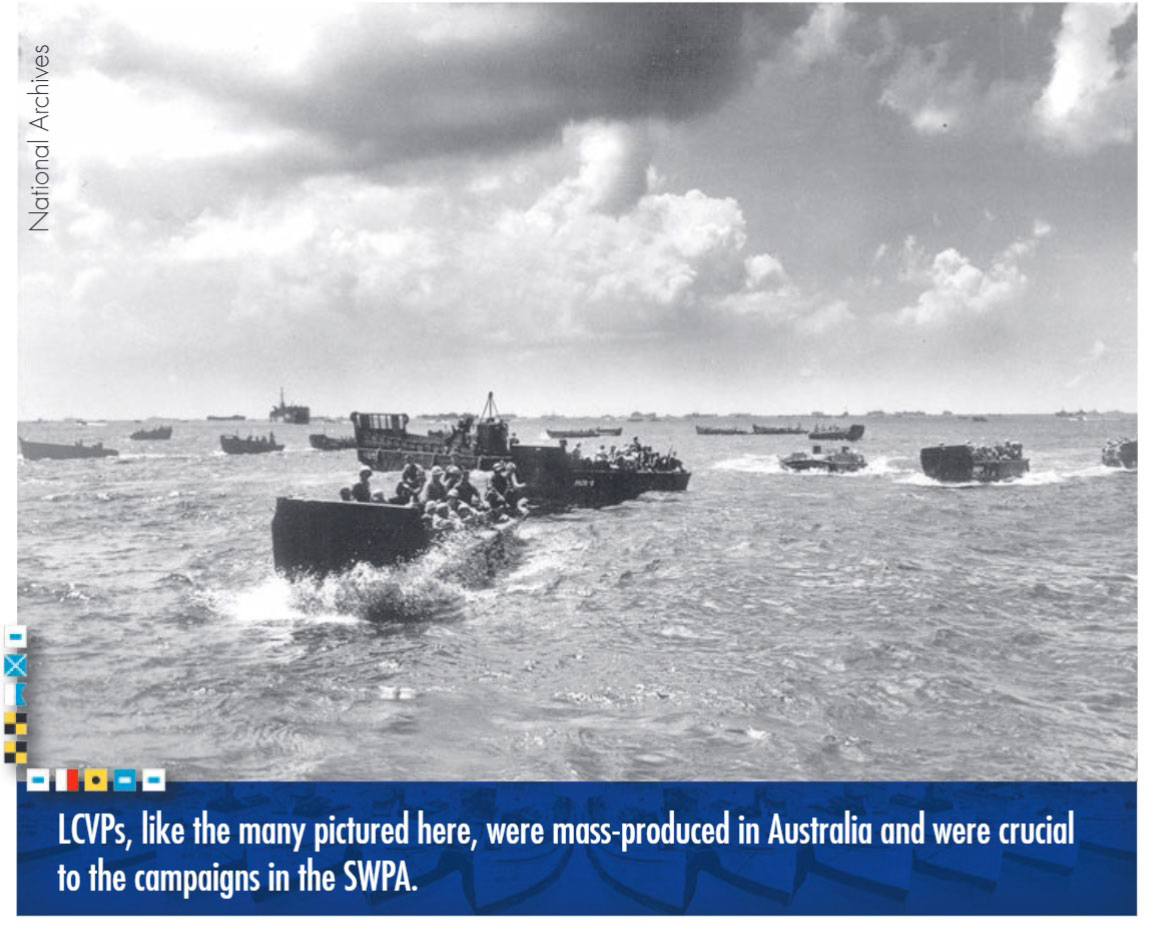

U. S. Army Special Engineers

The Army introduced the 2d ESB into the SWPA in 1943. This increased LCVPs, like the many pictured here, were mass-produced in Australia and were crucial to the campaigns in the SWPA. the Army’s capability to move and sustain Allied forces during the New Guinea Campaigns. These engineers also operated in an environment in which “improvisation was the rule rather than the exception.”45 The Boat and Shore sections of the 2d ESB brought some added measure of organization to forward cargo discharge sites. In a typical operation, once the amphibious assault wave passed across the beach and into the jungle, the “shore engineers quickly organized the job of unloading supplies and getting them distributed over hastily-constructed roadways to their proper dump sites.”46 The engineers also developed an ingenious way of conducting field boat repair. In one instance, repairmen from the 562d Boat Maintenance Battalion “constructed log barriers on the beach at low tide and brought the boat over at high tide. When the tide receded, the boat was left high and dry and the prop could be changed easily.”47 This service was especially important in areas with high concentrations of coral reefs around an amphibious assault or cargo discharge site.

Photo from the National Archives.

The 2d ESB also had to build its own boats. The War Department attempted a new method of transporting a large quantity of small assault boats to Australia quickly and efficiently. In a Washington Daily News article dated 27 March 1945, correspondent Lee Miller reported on the brigade’s arrival in Australia. “But [the Brigade] didn’t have a single boat. The plan was to ship the boats knocked down and assemble them in Australia.” The 2d ESB also had to construct the assembly facility. “On April 7, 1943, the first plywood LCVP (Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel) was turned out.” More than a thousand of these boats followed out of the Cairns, Australia, plant.48 These small vessels provided numerous advantages to Allied forces in the SWPA in support of General MacArthur’s campaigns. Eventually, Allied forces were able to use a greater number of traditional ocean cargo vessels to sustain the closing part of the New Guinea Campaigns and subsequent objectives supporting the U.S. Joint Chiefs’ Pacific theater campaign plan.

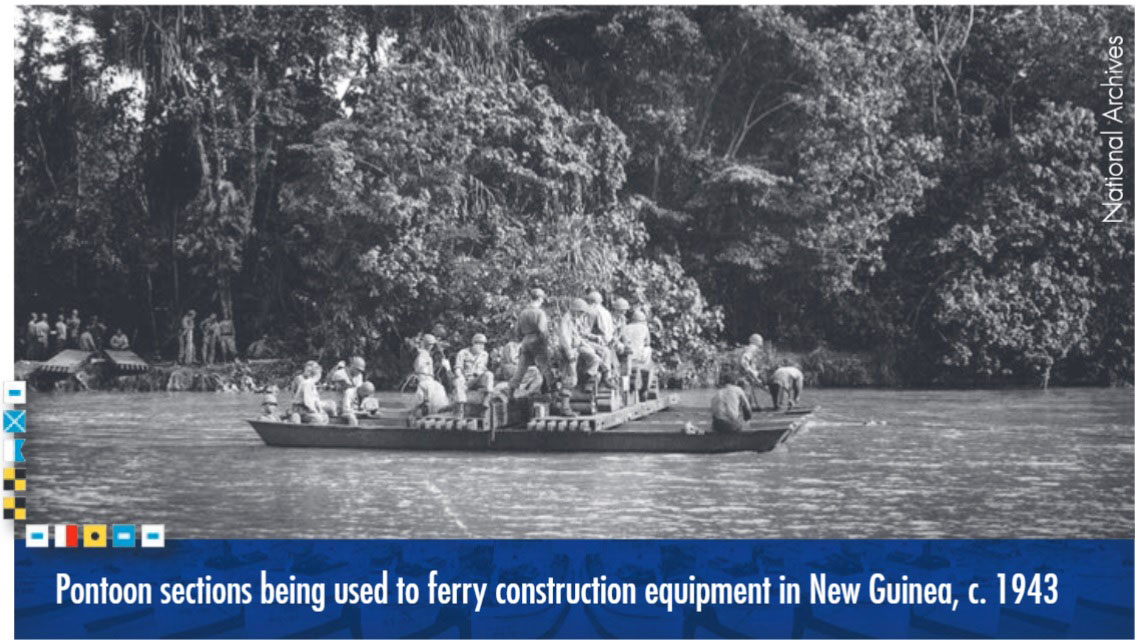

Photo from the National Archives.

Rudimentary port conditions at forward bases often created delays in discharging cargo from larger vessels. In some locations, such as Lae, the U.S. Army engineers had to build expedient docks. To mitigate this roblem, Sheridan Fahnestock (now a major) developed another innovative idea. To accommodate larger vessels, he loaded steel pontoon sections with construction equipment, installed a motor on each, and sailed the entire rig from Oro Bay to Lae. Once there, construction workers unloaded the supplies and equipment and then moored the pontoons together to create a functioning dock. This type of dock was not perfect but did allow up to six cargo vessels to discharge at the same time under austere conditions.49 Cargo handling under such circumstances was never easy and often resulted in many cargo vessels waiting days or weeks to unload due to a lack of berthing.

Photo from the National Archives.

Conclusion

The impact of the U.S. Small Ships Section and the 2d ESB in the SWPA was decisive. Since the Navy’s Pacific Fleet was unable to provide enough vessels to support SWPA operations early in the war, the U.S. Army Small Ships Section enabled General MacArthur’s forces to proceed with an amphibious campaign beginning in 1942. The 2d ESB complemented this effort in 1943 by employing additional watercraft and managing forward tactical discharge sites. MacArthur understood that the battle for New Guinea was “entirely dependent upon lines of communication.”50 His logisticians knew they had to rely on sealift along these lines to support Allied forces along New Guinea’s north shore. Resupply by sea offered the most feasible means of transferring large quantities of cargo to forward combat locations. The U.S. Small Ships and 2d ESB ef fectively established and maintained these primary lines of communication. Brig. Gen. Stephen Chamberlin, MacArthur’s assistant chief of staff, G–3, reflected on the importance this had on Allied operations. He stated that “if it had not been for the small Dutch freighters and even smaller miscellaneous craft” moving personnel, equipment, and supplies, “he doubted if the campaign for [Buna’s] capture would have succeeded, as air transport could not meet all the supply requirements.”51

Photo from the National Archives.

The contributions of Army transportation organizations in the SWPA have been largely forgotten. Units including the U.S. Small Ships Section and 2d ESB provided a much-needed capability to MacArthur’s forces at a time when no other resources were available to sustain combat operations in New Guinea. In fact, the modern U.S. Army fleet of coastal support craft can trace its origin back to small boat operations during the Second World War. More importantly, many historical narratives on the Pacific War have largely ignored the contributions of Australian citizens toward the war effort. Fortunately, U.S. and Australian government officials have recently started to recognize the war time service of Australians serving on American-flagged vessels. This attention is primarily due to the efforts of veterans and historians striving to preserve these relevant, but lesser-known aspects of the Second World War.

The accomplishments of the Army’s technical service organizations and their Allied foreign-national employees are just as important to Second World War history as combat narratives from the war. This lesser-explored aspect of the war provides greater insight into the success of Allied forces against the Japanese. Combat forces in the SWPA could not have advanced on Japanese Army positions without the presence of sea and air transport assets and without the support of Australian and American industrial bases. American logisticians discovered unique ways to sustain General MacArthur’s forces against some of the greatest odds. In particular, Army service organizations in the SWPA demonstrated that Western ingenuity was prevalent throughout the battlefield, not just along the front lines.

Author's Note

The author is deeply indebted to Richard Killblane, the U.S. Army Transportation Corps historian, and his staff at the U.S. Army Transportation Museum at Fort Eustis, Virginia, for their assistance in researching source material for this project.

Notes

1 Martin Van Creveld, Supplying War: Logistics from Wallenstein to Patton, 2d ed. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 236.

2 Richard M. Leighton and Robert W. Coakley, Global Logistics and Strategy: 1940–1943 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 2006), p. 143.

3 John Kennedy Ohl, Supplying the Troops: General Somervell and American Logistics in WWII (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1994), p. 198.

4 Samuel Milner, Victory in Papua (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1957), p. 58. Wairopi, New Guinea, provides a prime example of the restrictive terrain along the Kokoda rail. The site is located thirty miles southwest of Buna, where “a wire-rope bridge, from which the place took its name, spanned the immense gorge of the Kumusi River, a broad turbulent stream subject to dangerous undertows and flash floods.”

5 Douglas MacArthur, Reminiscences (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964), p. 169.

6 Stephen R. Taaffe, MacArthur’s Jungle War: The 1944 New Guinea Campaign (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1998), p. 230.

7 Ladislaw Reday, Raggle Taggle Fleet (Coomba Park, New South Wales: Ernest Flint, 2000), p. 35.

8 James R. Masterson, U.S. Army Transportation in the Southwest Pacific Area, 1941–1947 (Washington, D.C.: Transportation Unit, Historical Division Special Staff, U.S. Army, 1949), pp. 190–91.

9 It may have also helped that the Fahnestock family enjoyed close ties with the Roosevelt family as well as associations with some U.S. senators and representatives. Likewise, General Wilson also had friends among President Roosevelt’s closest advisers.

10 Bill Lunney and Frank Finch, Forgotten Fleet: A History of the Part Played by Australian Men and Ships in the U.S. Army Small Ships Section in New Guinea, 1942–1945 (Medowie, New South Wales: Forfleet Publishing, 1995), p. 11; Ernest A. Flint, “The Formation and Operation of the US Army Small Ships in World War II,” United Service 55, no. 4 (March 2005): 15–20.

11 Flint, “The Formation and Operation of the US Army Small Ships in World War II,” pp. 15–16.

12 Masterson, U.S. Army Transportation in the Southwest Pacific Area, p. 192; Lunney, Forgotten Fleet, p. 11.

13 Joseph Bykofsky and Harold Larson, The Transportation Corps: Operations Overseas, United States Army in World War II (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1990), p. 430. The Army Transportation Service changed the name of the Small Ships Supply Section at least twice after assuming control of this organization on 29 May 1942. Subsequent names included Small Ships Section (1942) and Small Ships Division (1943). Lido Mayo, The Ordnance Department: On Beachhead and Battlefront (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1991),p. 69. In addition to Masterson, Lida Mayo is the only other official historian in the World War II series to refer to this organization as the Small Ships Section. In their memoirs, veterans generally refer to this organization as the “U.S. Small Ships.” Subsequent paragraphs in this essay reflect this tradition.

14 Reday, Raggle Taggle Fleet, p. 32. Savage was responsible for inspecting and accepting boats purchased or commandeered by the Army. He previously worked for J. J. Savage and Son Boat Builders of Victoria in Australia.

15 Lunney, Forgotten Fleet, p. 11.

16 On 15 May 2001, the U.S. Small Ships Association presented a commemorative plaque to the Grace Hotel depicting these dates. A replica resides at the U.S. Army Transportation Museum at Fort Eustis, Virginia.

17 Masterson, U.S. Army Transportation in the Southwest Pacific Area, pp. 193–94.

18 Lunney, Forgotten Fleet, p. 11.

19 Mayo, The Ordnance Department: On Beachhead and Battlefront, p. 71. Mayo identifies 1st Lt. Bruce Fahnestock as the head of the Small Ships Section. However, more recent authors, such as Bill Lunney and Ladislaw Reday, suggest that his brother, Capt. Sheridan Fahnestock, was the next ranking member and senior operations officer of the Small Ships Section under the command of Major Bradford. Lt. Bruce Fahnestock did not serve with the Small Ships for very long. He was killed on 18 October 1942 in a friendly fire incident involving an American B–24 bomber during the Buna landings in New Guinea.

20 Masterson, U.S. Army Transportation in the Southwest Pacific Area, p. 193.

21 Flint, “The Formation and Operation of the US Army Small Ships in World War II,” p. 3.

22 Reday, Raggle Taggle Fleet, p. 34.

23 Flint, “The Formation and Operation of the US Army Small Ships in World War II,” pp. 3–5.

24 Ibid., p.8.

25 Lunney, Forgotten Fleet, p. 12. Norm Oddy accepted a job with the Small Ships Section in July 1942. Flint, “The Formation and Operation of the US Army Small Ships in World War II,” p. 5. Surviving members of the U.S. Small Ships used this argument recently with members of the Australian Parliament to convince their government to recognize the wartime service of Australians serving on these vessels.

26 Lunney, Forgotten Fleet, p. 12.

27 Mayo, The Ordnance Department: On Beachhead and Battlefront, p. 71. The two vessels involved were the King John and the Timoshenko. Lunney, Forgotten Fleet, p. 16. Lt. Col. Laurence McKenney served as the commander of this particular Small Ships mission.

28 Milner, Victory in Papua, p. 82.

29 Lunney, Forgotten Fleet, p. 14.

30 Ibid., p. 30.

31 James Campbell, The Ghost Mountain Boys: Their Epic March and the Terrifying Battle for New Guinea—The Forgotten War of the South Pacific (New York: Crown Publishers, 2007), pp. 168–69.

32 Milner, Victory in Papua, pp. 169–71.

33 Lunney, Forgotten Fleet, pp. 26–28.

34 Ibid., p. 53.

35 Bykofsky, The Transportation Corps: Operations Overseas, p. 449.

36 “U.S. Army Small Ships Section USASOS [U.S. Army Services of Supply] in Australian Waters During WWII,” accessed 23 Oct 2011, http://www.ozatwar.com/usarmy/usarmys mallships.htm.

37 Interv, James Atwater and Richard Killblane with David Everett, Australian veteran of the U.S. Small Ships, 16 May 2010, interview WS218870, transcript, U.S. Army Transportation Museum, Fort Eustis, Va. Everett joined the Small Ships at around age seventeen as a seaman apprentice on a ketch. His formal training included about four weeks of maritime school in Walsh Bay.

38 Interv, James Atwater with Bernie O’Brian, Australian veteran of the U.S. Small Ships, 15 May 2010, interview WS218869, transcript, U.S. Army Transportation Museum, Fort Eustis, Va. O’Brian became a merchant seaman at age seventeen as a galley boy on a Norwegian cargo vessel. He returned to Sydney after the Japanese sank his vessel and joined the Small Ships. Before serving on the FS–285, he recalls serving on an American lumber transport, the Esther Johnson, the FS–12-B, an oil ship, and a tugboat.

39 Daniel E. Barbey, MacArthur’s Amphibious Navy: Seventh Amphibious Force Operations, 1943–1945 (Annapolis, Md.: U.S. Naval Institute, 1969), p. 46. LSTs (Landing Ship, Tanks) are capable of transporting large numbers of troops, vehicles, and cargo and discharging them directly onto a beach. LCIs (Landing Crafts, Infantry) are capable of transporting troops and discharging them directly onto a beach. An LCI is typically smaller than an LST.

40 John Kennedy Ohl, Supplying the Troops: General Somervell and American Logistics in WWII (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1994), p. 214.

41 Lunney, Forgotten Fleet, p. 28.

42 Interv, James Atwater with Bernard Smith, Australian veteran of the U.S. Small Ships, 15 May 2010, interview WS218865, transcript, U.S. Army Transportation Museum, Fort Eustis, Va. Smith first went to sea at age fifteen serving as a junior navigator on board the Queen Elizabeth, which was ferrying troops from Australia to the Middle East at the time. In 1941, at age seventeen, he joined the U.S. Small Ships and served on the Muscutta, a four-mast sailing ship for his first contract. After renewing his contract, he served as a coxswain on the Moamoa, the Caledon, and a crash ship supporting Army Air Forces (AAF) rescue operations. Smith served with the Small Ships until 1944.

43 Peter S. Kindsvatter,American Soldiers: Ground Combat in the World Wars, Korea, and Vietnam (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2003), p. 38.

44 Masterson, U.S. Army Transportation in the Southwest Pacific Area, p. 485.

45 A History of the 2d Engineer Special Brigade, 1942–1945 (Harrisburg, Pa.: Telegraph Press, 1946), pp. 62–63.

46 Ibid., p. 46.

47 Ibid., p. 33.

48 Ibid., p. 267. This article is reprinted in the history of the 2d Engineer Special Brigade

49 Masterson, U.S. Army Transportation in the Southwest Pacific Area, pp. 442–43.

50 Milner, Victory in Papua, p. 102. This book is based on an extract from General Head quarters Southwest Pacific Area Operational Instructions No. 19, 1 Oct. 42.

51 Barbey, MacArthur’s Amphibious Navy, p. 9.