The Black Buffalo Soldiers Who Biked Across the American West

David Kindy

Members of the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps pose on Minerva Terrace at Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone National Park in 1896. Montana Historical Society

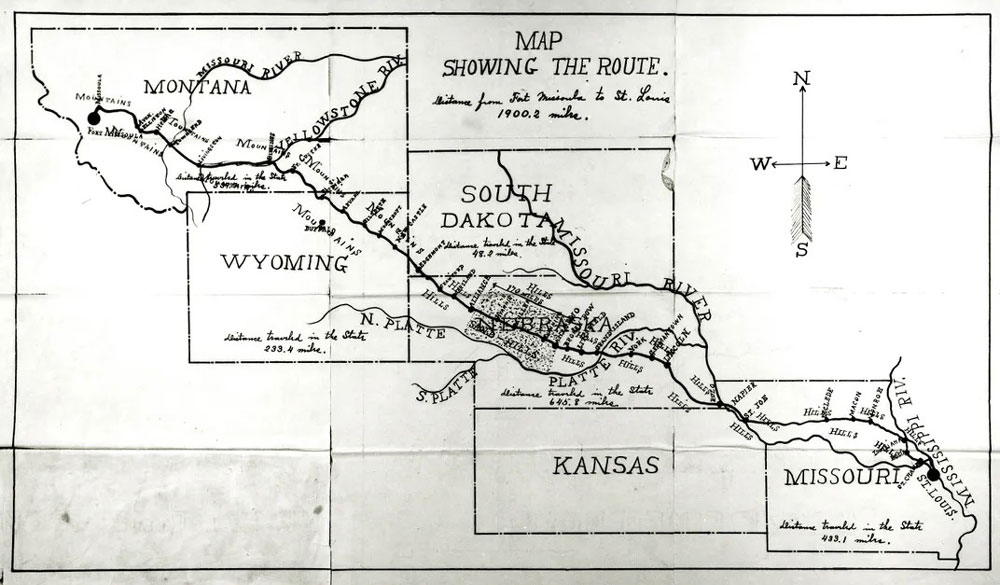

In 1897, the 25th Infantry Regiment Bicycle Corps embarked on a 1,900-mile journey from Montana to Missouri

The long line of bicyclists caught the eye of residents in Big Timber, Montana. Dressed in blue gingham shirts and campaign hats, the United States Army riders had large knapsacks with bedrolls strapped to their handlebars and rifles slung over their backs. Tired and bedraggled, members of the cycling caravan smiled as they rode into the tiny town next to the Yellowstone River in late June 1897.

Comprising 20 soldiers, 2 officers and 1 reporter, the group was about one week into a cross-country trek designed to show Army brass the efficacy of transporting troops by bicycle. At the time, just before the start of the 20th century and the dawn of automobiles, much of the world was fixated on cycling as a means of mobility. Officially dubbed the 25th Infantry Regiment Bicycle Corps, the men were members of one of six racially segregated units formed by the Army just after the Civil War. Black enlistees led mainly by white officers, the regiments served on the nation’s Western frontier, where they clashed with Native Americans who supposedly nicknamed them Buffalo Soldiers due to their curly hair’s resemblance to buffalo manes.

To avoid thick mud and soft sand, the soldiers walked their bikes along railroad tracks. National Archives

Also known as Iron Riders, the volunteer bicycle corps set out from Fort Missoula, Montana, on June 14, 1897, embarking on a 1,900-mile odyssey to St. Louis, Missouri. They hadn’t planned to spend much time in the town of Big Timber, but an elderly, exuberant Civil War veteran convinced them to stick around, insisting on buying drinks for the soldiers at a local tavern.

During their 41-day journey, the cyclists pedaled up mountains, through forests, over deserts and across rivers, riding on dirt trails, unpaved roads and railroad tracks to avoid the sticky “gumbo” mud, as they called it. They biked upward of 50 miles per day, alternatively enduring snow, freezing sleet, hail, heavy rain and oppressive heat. Their feat made headlines around the country and demonstrated the Buffalo Soldiers’ tenacity at a time of widespread racism both in the military and outside of it.

“They did an amazing thing,” says Kristjana Eyjolfsson, director of education at the Historical Museum at Fort Missoula. “It’s great to think about their experience going across country, how they might have impacted people that they met and how they captured the attention of the world since it was covered in so many newspapers.”

This year, in honor of the 125th anniversary of the Iron Riders’ trip, local historical groups are hosting a series of commemorative events along the cyclists’ route. The action kicked off with a ceremonial bike ride that started at 5:40 a.m. today—the same time the soldiers began their ride.

By 1897, the idea of using bicycles—introduced in the early 19th century and finetuned over the following decades—to transport troops had been around for some time. Some sources suggest that messengers and scouts fighting in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 to 1871 used two-wheeled vehicles. Militaries in Britain, Spain and other countries tested bicycles and found they were well-suited for reconnaissance and delivering dispatches across a variety of terrain. Bikes also proved less expensive and easier to maintain than the horses typically used by cavalries.

In the U.S., Lieutenant General Nelson A. Miles—a veteran of the Civil War and the American Indian Wars—emerged as a key advocate of using bikes in the Army. Following the example of the First Signal Corps of the Connecticut National Guard, which in 1891 became the first American unit to formally utilize bicycles, Miles authorized several trials to determine the effectiveness of the new mode of transportation, including relay teams that delivered messages from Chicago to New York and Washington, D.C. to Denver.

The 1,900-mile route traversed mountains, rivers and deserts in five states. National Archives

“The bicycle has been found exceedingly useful in reconnoitering different sections of the country, and it is my purpose to use to some extent troops stationed at different posts to make practice marches and reconnaissance’s [sic],” he wrote in an 1895 report.

A newly commissioned lieutenant fresh out of West Point soon proposed a more comprehensive test. As one of the white officers stationed with the 25th Infantry at Fort Missoula, James A. Moss wanted to send Buffalo Soldiers on a lengthy ride across rough terrain in the West. His request—designed to gauge how both troops and bicycles would fare in such a challenge—eventually ended up with Miles, who approved it in 1896.

With Miles’ backing, Moss set the wheels in motion for the Iron Riders. He approached several bicycle makers for donations of equipment. A.G. Spalding & Bros.—which would later become a major manufacturer of sporting goods—agreed to participate and developed the Military “Special,” a modified version of one of its popular models.

Design changes included a sturdier front fork that absorbed the bumps of the rough roads, an ergonomically designed seat for comfort on long rides and metal tire rims. (Wheels in those days were often made of wood, which tended to break under harsh conditions.)

Moss began drilling his troops almost immediately, leading them on daily rides in increasingly challenging conditions. In August 1896, the bicycle corps embarked on a round-trip expedition to Yellowstone National Park, about 275 miles southeast of Fort Missoula.

The 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps in Yellowstone National Park Montana Historical Society

Including Moss, nine men participated in the Yellowstone trial. Among them were Black soldiers Sergeant Dalbert P. Green and Corporal John G. Williams; musician William W. Brown; and privates Frank L. Johnson, William Proctor, William Haynes, Elwood Forman and John Findley, who had previously been employed at the Imperial Bicycle Works in Chicago and knew how to repair bicycles.

The ride was a success, though not without its challenges. The men had to ride on bikes that, when packed with gear and food, weighed almost 80 pounds each. Bad weather, flat tires and equipment failures slowed progress, and the soldiers were often tired from pedaling up steep inclines on their single-gear bicycles. (Modern racing and touring bicycles have upward of 27 gears that make pedaling easier when adjusted to fit specific terrain and conditions.) Despite this, they covered 797 miles in 126 hours of biking and even stopped for an iconic photo at the Minerva Terrace in Mammoth Hot Springs.

By the following year, Moss and his men were ready to tackle a longer ride to St. Louis. The operation took considerable planning, including scheduling the resupply of food, clothing and replacement gear at key drop-off points.

For the 1897 journey, Moss expanded the unit to 20 soldiers. They included five men from the Yellowstone trip—Findley, Forman, Haynes, Johnson and Proctor—as well as Sergeant Mingo Sanders; Lieutenant Corporal Abram Martin; musician Elias Johnson; and privates George Scott, Hiram L. B. Dingman, Travis Bridges, John Cook, Richard Rout, Eugene Jones, Sam Johnson, William Williamson, Sam Williamson, John H. Wilson, Samuel Reid and Francis Button.

Excitement abounded as the June 14 start date approached. Moss wrote that his men were “bubbling over with enthusiasm, ... about as fine a looking and well-disciplined a lot as could be found anywhere in the United States Army.”

The Buffalo Soldiers often had to carry their bikes over swift-running rivers and streams. National Archives

This time around, Moss’ team included a doctor—Lieutenant James M. Kennedy, the regiment’s assistant surgeon—and a reporter, Edward H. Boos of the Daily Missoulian. Boos’ articles appeared in newspapers across the country, providing details of what happened during the ride.

Other than Moss’s Army reports, Boos’ accounts provide the only known record of the Buffalo Soldiers’ experiences during this historic journey. (Scholars have found no written documentation by the Iron Riders themselves.) Both narratives reflect the racial stereotypes and racism of the day, often focusing on the vernacular language used by the Black soldiers.

In the July 17 issue of the Daily Missoulian, Boos detailed how the bicycle corps navigated “mountain roads, cactus beds and wagon roads.” He added, “It was a grand ride and beset with many difficulties, from the incessant rains along the route. Few accidents were reported, and those of no consequence. There were no delays made for pleasure and the boys pedaled hard to make a good record and have accomplished it. The whole world was watching the result.”

The route took the bicycle corps through woodlands and deserts in five states: Montana, Wyoming, South Dakota, Nebraska and Missouri. As they crossed the Continental Divide, the soldiers straddled the mountain top and looked down the Atlantic and Pacific slopes. They had to ford swift rivers, often carrying their bicycles over their heads, and traverse railroad tracks to avoid the viscous mud that swallowed up their tires and prevented them from riding.

3 Different eye witnesses vary in the exact number of wagons in the official French train from 210 to 220. Dr. Robert Selig believes the number of wagons may have been as high as 300.

“It was very grueling for them,” says Erick Cedeño, an extreme adventure cyclist who is recreating the trip to mark the quasquicentennial of the original ride. He plans to arrive in St. Louis on July 24, the anniversary of the original ride’s conclusion.

“There’s a section just before Helena, Montana, that’s 12 miles of an uphill climb,” Cedeño says. “It’s exhausting. ... Most [of the men] learned to ride while being trained in drills and shorter trips. What really amazes me is that they were able to ride 1,900 miles on a single speed.”

Lieutenant James Moss led the bicycle corps on its historic ride across the American West. University of Montana

While still high in the Rockies in mid-June, the Buffalo Soldiers encountered a spring snowstorm that coated their tents. The shivering troops had to wait a few hours for the snow to melt before resuming their journey.

That moment resonated strongly with Bobby McDonald, who is helping to organize this year’s commemoration. President of the Black Chamber of Commerce of Orange County and a member of the Buffalo Soldiers 9th & 10th (Horse) Cavalry National Association, he’s spent the past few months traveling between California and Montana to prepare for the anniversary. In May, he was surprised by a fickle change in the weather while at Fort Missoula.

“It was snowing,” says McDonald, whose father served with the 24th Infantry Regiment during World War II and the Korean War. “That’s when it really hit me. These guys had to go through this. I realized what a monumental achievement they had accomplished.”

In late June and early July, the Iron Riders faced extreme heat and a lack of potable water in the Sand Hills of Nebraska. Several men, including Moss, became ill after drinking alkaline water, which has a higher pH level than regular drinking water, and had to catch up with the rest of the group via train; in a report to the War Department, Moss wrote, “[W]e suffered considerably from its bad effects. For several hundred miles through these States the only water fit to drink had to be gotten from the railroad water tanks.”

For the most part, the Buffalo Soldiers received warm welcomes from the public for undertaking the arduous journey. The farther south they went, however, the more discrimination they faced. As the group approached Missouri, a border state that only abolished slavery in 1865, they were turned away from camping on certain farms.

“Indeed, equal treatment did not accompany the enthusiasm that met the bicycle corps upon completion of their journey,” wrote Alexandra V. Koelle in a 2010 article for the Western Historical Quarterly. “While the men had shared cooking duties and close quarters on the ride itself, once in St. Louis, the white and Black members of the expedition ate their meals in separate locations: The officers dined at the Cottage (Hotel) in Forest Park while the troops ate in the bicycle shed.”

At the end of the journey on July 24, mounted police and almost 1,000 amateur cyclists from a local club escorted the Buffalo Soldiers into St. Louis, where they took part in a parade and receptions. An estimated 10,000 people visited the corps’ campsite.

Moss considered the expedition an unqualified success. Over 1,900 miles, his men averaged a punishing 55.9 miles daily on the 34 days they traveled, maintaining a speed of 6.3 miles per hour. (Seven days were set aside for rest and repairs.)

“The practical result of the trip shows that an Army bicycle corps can travel twice as fast as cavalry or infantry under any conditions, and at one third the cost and effort,” Moss told the United States Army and Navy Journal.

The men had planned to ride part of the way back to Fort Missoula, but the Army instead decided to send them back by train. Though Moss continued to push for bicycle expeditions, technological advancements and an impending war got in the way of these plans. The Army disbanded the bicycle corps, realizing that that mechanized infantry, not bicycles, was the way of the future.

When the Spanish-American War erupted in the spring of 1898, the 25th Infantry was one of the first units mobilized. Its members distinguished themselves in Cuba by coming to the aid of Colonel Theodore Roosevelt and the Rough Riders at the Battle of San Juan Hill.

This valiant support was quickly forgotten in light of the so-called Brownsville Affair, which took place in Brownsville, Texas, in August 1906. Amid heightened racial tensions between white locals and the Black soldiers stationed at nearby Fort Brown, a gunfight broke out, resulting in the death of one white civilian and the injury of another. White residents blamed the Buffalo Soldiers for the incident, ignoring the regiment commanders’ testimony that the all of the men had been in their barracks at the time of the attack.

Fort Brown, where the 25th Infantry was stationed at the time of the Brownsville Affair SMU Central University Libraries via Wikimedia Commons

In 1908, then-President Roosevelt ordered the dishonorable discharge of 167 soldiers from the 25th Infantry Regiment for their alleged “conspiracy of silence.” The decision drew criticism from both Black and white observers, with supporters of the soldiers pointing to evidence that the men had been framed.

Several white officers and politicians tried to have the order reversed to no avail. They vouched for the character of the men, including Mingo Sanders, one of the Iron Riders and a hero of the Spanish-American War. He was one year shy of retirement and was denied military benefits because of the discharge.

Brigadier General Andrew Burt, who’d served as a colonel in the 25th before his retirement, testified in front of a Senate committee that “there was no better first sergeant in the army; that [Sanders’] veracity was beyond question, and that he could be depended upon under all circumstances.”

Congress only reversed Roosevelt’s ruling in 1972, after a historian’s investigation of the affair brought it to the public’s attention again. The legislative body authorized honorable discharges for all 167 men, offering $25,000 to one of the two survivors whom congressional staffers managed to track down and awarding $10,000 each to a dozen widows of the now-deceased soldiers.

Moss, who was born and raised in Louisiana, continued to lead African American troops throughout his career. Despite espousing racist views, he came to respect the men who fought and died beside him in the Spanish-American War and World War I, when he was a colonel in the all-Black 367th Infantry Regiment.

“I commanded colored troops in the Cuban campaign and in the Philippine campaign,” he wrote. “... At no time did they ever falter at the command to advance nor hesitate at the order to charge. I am glad that I am to command colored soldiers in this, my third campaign—in the greatest war the world has ever known.”